2012 | Forum

The Blind Spots of Visibility

The Forum 2012 goes into the festival with as diverse a selection as ever before. In our interview, section director Christoph Terhechte discusses new generational conflicts, the audience’s yearning for pictures and a cinematography nearly lost forever.

Film stills from the Forum programme 2012

Hannah Hoekstra, Ali Ben Horsting

Hemel by Sacha Polak

NLD/ESP 2012, Forum

Hannah Hoekstra

Hemel by Sacha Polak

NLD/ESP 2012, Forum

Vojtěch Machuta, Jan Vaši, Jiří Černý, Martin Pechlát, Natálie Řehořová

Prílis mladá noc | A Night Too Young by Olmo Omerzu

CZE/SVN 2012, Forum

Jan Vaši, Vojtěch Machuta

Prílis mladá noc | A Night Too Young by Olmo Omerzu

CZE/SVN 2012, Forum

Raúl Godoy, Jaime Pedruelo

Sleepless Knights by Stefan Butzmühlen, Cristina Diz

DEU 2012, Forum

Sleepless Knights by Stefan Butzmühlen, Cristina Diz

DEU 2012, Forum

Thure Lindhardt, Sabine Timoteo

Formentera by Ann-Kristin Reyels

DEU 2012, Forum

© unafilm Berlin GmbH

Hiver nomade | Winter Nomads by Manuel von Stürler

CHE 2012, Forum

Hiver nomade | Winter Nomads by Manuel von Stürler

CHE 2012, Forum

Marek Kępiński, Tomasz Tyndyk, Agnieszka Podsiadlik

Sekret | Secret by Przemyslaw Wojcieszek

POL 2012, Forum

Agnieszka Podsiadlik

Sekret | Secret by Przemyslaw Wojcieszek

POL 2012, Forum

Escuela normal | Normal School by Celina Murga

ARG 2012, Forum

Escuela normal | Normal School by Celina Murga

ARG 2012, Forum

Mujin chitai | No Man's Zone by Fujiwara Toshi

JPN/FRA 2012, Forum

friends after 3.11 by Iwai Shunji

JPN 2011, Forum

friends after 3.11 by Iwai Shunji

JPN 2011, Forum

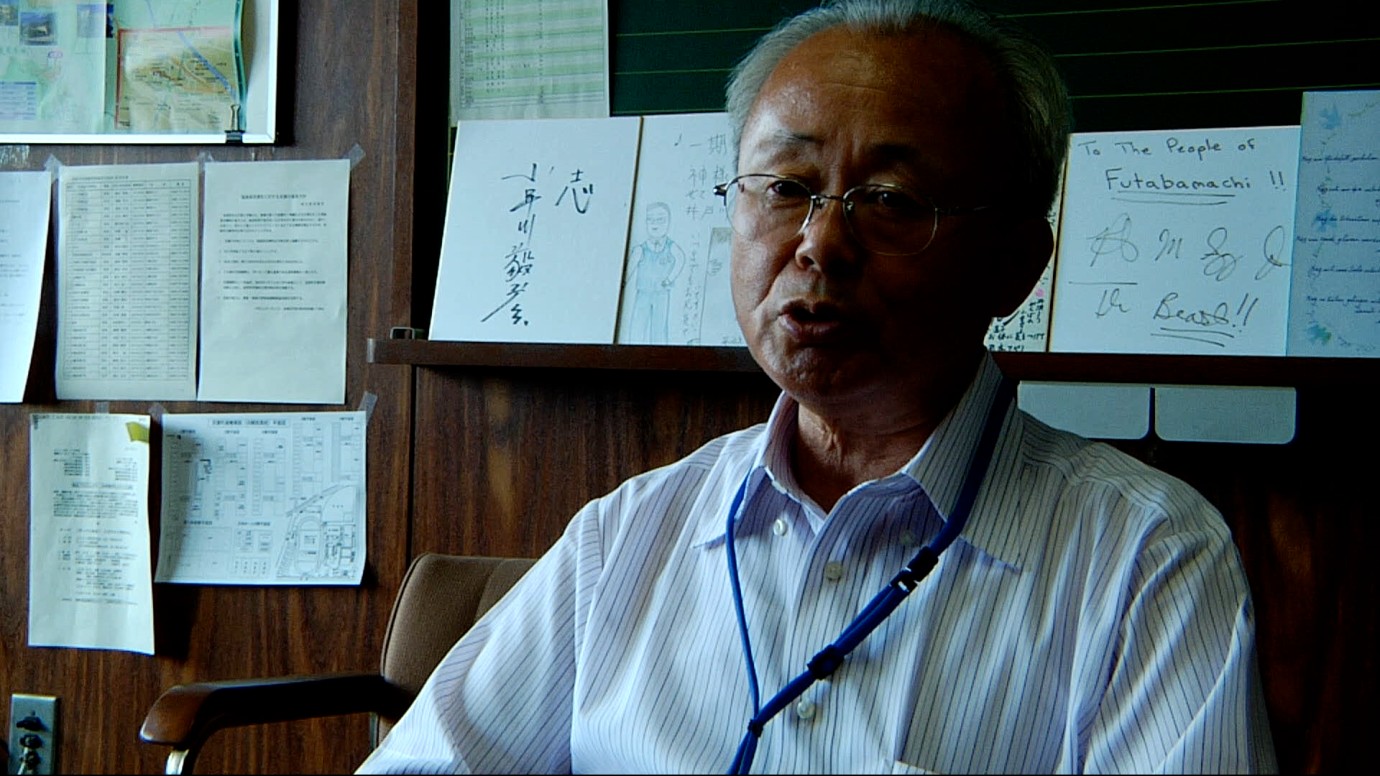

Nuclear Nation by Funahashi Atsushi

JPN 2012, Forum

Nuclear Nation by Funahashi Atsushi

JPN 2012, Forum

Le sommeil d'or | Golden Slumbers by Davy Chou

FRA/KHM 2011, Forum

Le sommeil d'or | Golden Slumbers by Davy Chou

FRA/KHM 2011, Forum

Puos Keng Kang | The Snake Man by Tea Lim Koun

KHM 1970, Forum

Puos Keng Kang | The Snake Man by Tea Lim Koun

KHM 1970, Forum

Mihashi Tatsuya, Aratama Michiyo

Suzaki Paradaisu Akashingo | Suzaki Paradise: Red Light by Kawashima Yuzo

JPN 1956, Forum

© 1956 NIKKATSU Corporation

Minamida Yoko, Sakai Frankie, Hidari Sachiko

Bakumatsu taiyoden | The Sun in the Last Days of the Shogunate by Kawashima Yuzo

JPN 1957, Forum

© 1957 NIKKATSU Corporation

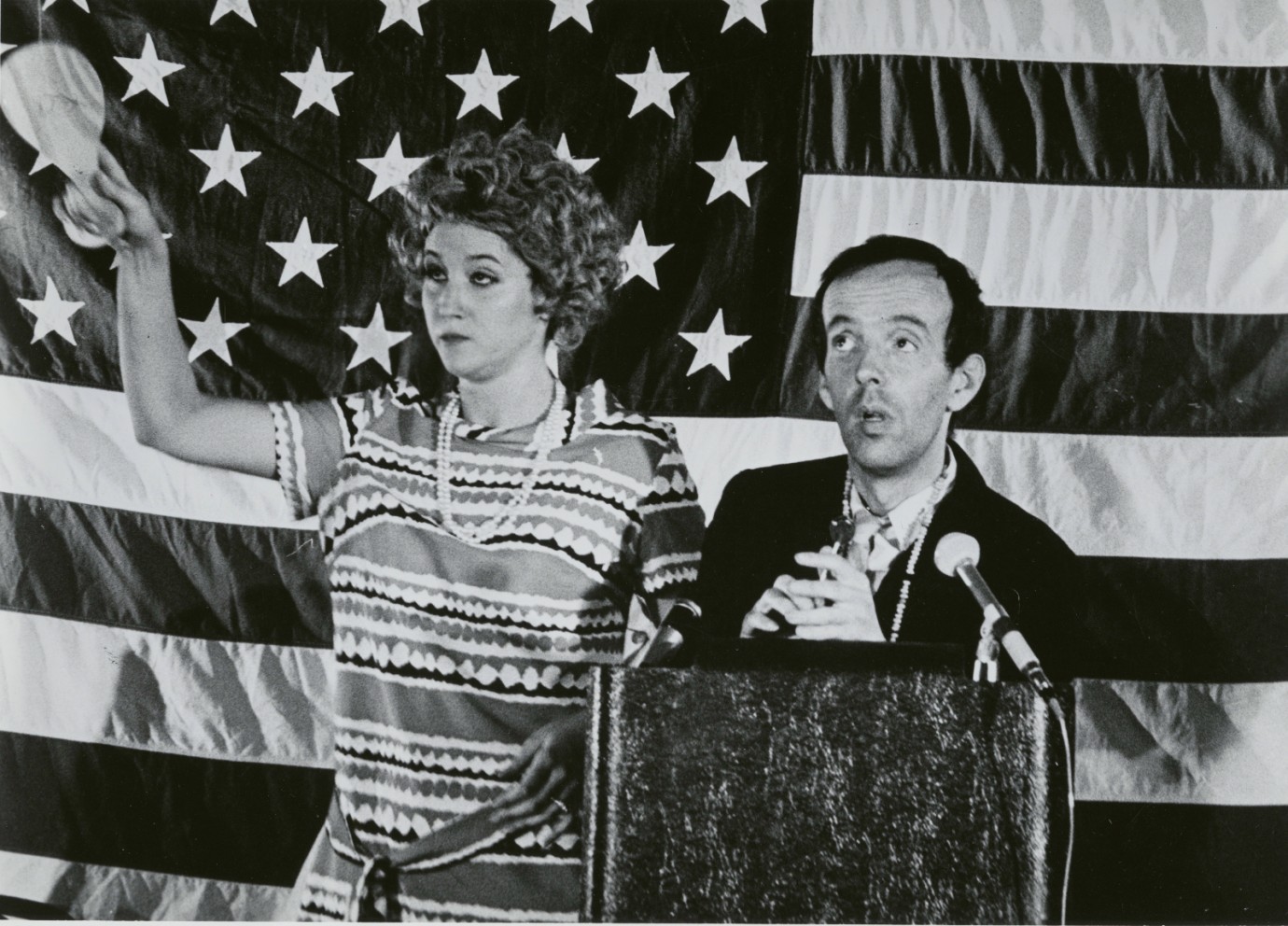

Sally Kirkland, Taylor Mead

Brand X by Wynn Chamberlain

USA 1970, Forum

© Gianfranco Mantegna, care of the New York Public Library

Tally Brown

Brand X by Wynn Chamberlain

USA 1970, Forum

© Gianfranco Mantegna, care of the New York Public Library

Tatjana Alexander

Spanien | Spain by Anja Salomonowitz

AUT 2012, Forum

Sofia Nicolaescu, Serban Pavlu

Toata lumea din familia noastra | Everybody in Our Family by Radu Jude

ROU/NLD 2012, Forum

Sofia Nicolaescu

Toata lumea din familia noastra | Everybody in Our Family by Radu Jude

ROU/NLD 2012, Forum

What Is Love by Ruth Mader

AUT 2012, Forum

Eugene Domingo

Ang Babae sa Septic Tank | The Woman in the Septic Tank by Marlon N. Rivera

PHL 2011, Forum

Ang Babae sa Septic Tank | The Woman in the Septic Tank by Marlon N. Rivera

PHL 2011, Forum

Bagrut Lochamim | Soldier / Citizen by Silvina Landsmann

ISR 2012, Forum

Bagrut Lochamim | Soldier / Citizen by Silvina Landsmann

ISR 2012, Forum

Paul Deno, Shaylena Mandigo

For Ellen by So Yong Kim

USA 2012, Forum

Paul Deno

For Ellen by So Yong Kim

USA 2012, Forum

Carlos Vallarino

La demora | The Delay by Rodrigo Plá

URY/MEX/FRA 2012, Forum

Roxana Blanco

La demora | The Delay by Rodrigo Plá

URY/MEX/FRA 2012, Forum

Ali Suliman

Al Juma Al Akheira | The Last Friday by Yahya Alabdallah

JOR/ARE 2011, Forum

Ali Suliman

Al Juma Al Akheira | The Last Friday by Yahya Alabdallah

JOR/ARE 2011, Forum

Ando Sakura, Iura Arata

Kazoku no kuni | Our Homeland by Yang Yonghi

JPN 2012, Forum

Esmail Khalaj, Taraneh Alidoosti

Paziraie Sadeh | Modest Reception by Mani Haghighi

IRN 2012, Forum

© Abbas Kosari

Beziehungsweisen | Negotiating Love by Calle Overweg

DEU 2012, Forum

© Calle-Overweg-Filmproduktion

Beziehungsweisen | Negotiating Love by Calle Overweg

DEU 2012, Forum

© Calle-Overweg-Filmproduktion

Johannes Brost, Léonore Ekstrand

Avalon by Axel Petersén

SWE 2011, Forum

© Måns Månsson

Avalon by Axel Petersén

SWE 2011, Forum

© Måns Månsson

Revision by Philip Scheffner

DEU 2012, Forum

© Svenja L. Harten / pong

Revision by Philip Scheffner

DEU 2012, Forum

© Svenja L. Harten / pong

in arbeit / en construction / w toku / lavori in corso | in the works | in arbeit by Minze Tummescheit, Arne Hector

DEU 2012, Forum

in arbeit / en construction / w toku / lavori in corso | in the works | in arbeit by Minze Tummescheit, Arne Hector

DEU 2012, Forum

Camila Murias

Salsipuedes by Mariano Luque

ARG 2012, Forum

Habiter / Construire | Living / Building by Clémence Ancelin

FRA 2012, Forum

Habiter / Construire | Living / Building by Clémence Ancelin

FRA 2012, Forum

Jaurès by Vincent Dieutre

FRA 2012, Forum

Jaurès by Vincent Dieutre

FRA 2012, Forum

Berk Hakman

Tepenin Ardi | Beyond the Hill by Emin Alper

TUR/GRC 2012, Forum

Tepenin Ardi | Beyond the Hill by Emin Alper

TUR/GRC 2012, Forum

Bestiaire by Denis Côté

CAN/FRA 2012, Forum

Bestiaire by Denis Côté

CAN/FRA 2012, Forum

Um Tae-goo, Park Se-jin

Kashi | Choked by Kim Joong-hyun

KOR 2011, Forum

Um Tae-goo

Kashi | Choked by Kim Joong-hyun

KOR 2011, Forum

Tiens moi droite | Keep Me Upright by Zoé Chantre

FRA 2012, Forum

Wagatsuma Miwako

Koi ni itaru yamai | The End of Puberty by Kimura Shoko

JPN 2011, Forum

Wagatsuma Miwako, Saito Yoichiro, Satsukawa Aimi, Sometani Shota

Koi ni itaru yamai | The End of Puberty by Kimura Shoko

JPN 2011, Forum

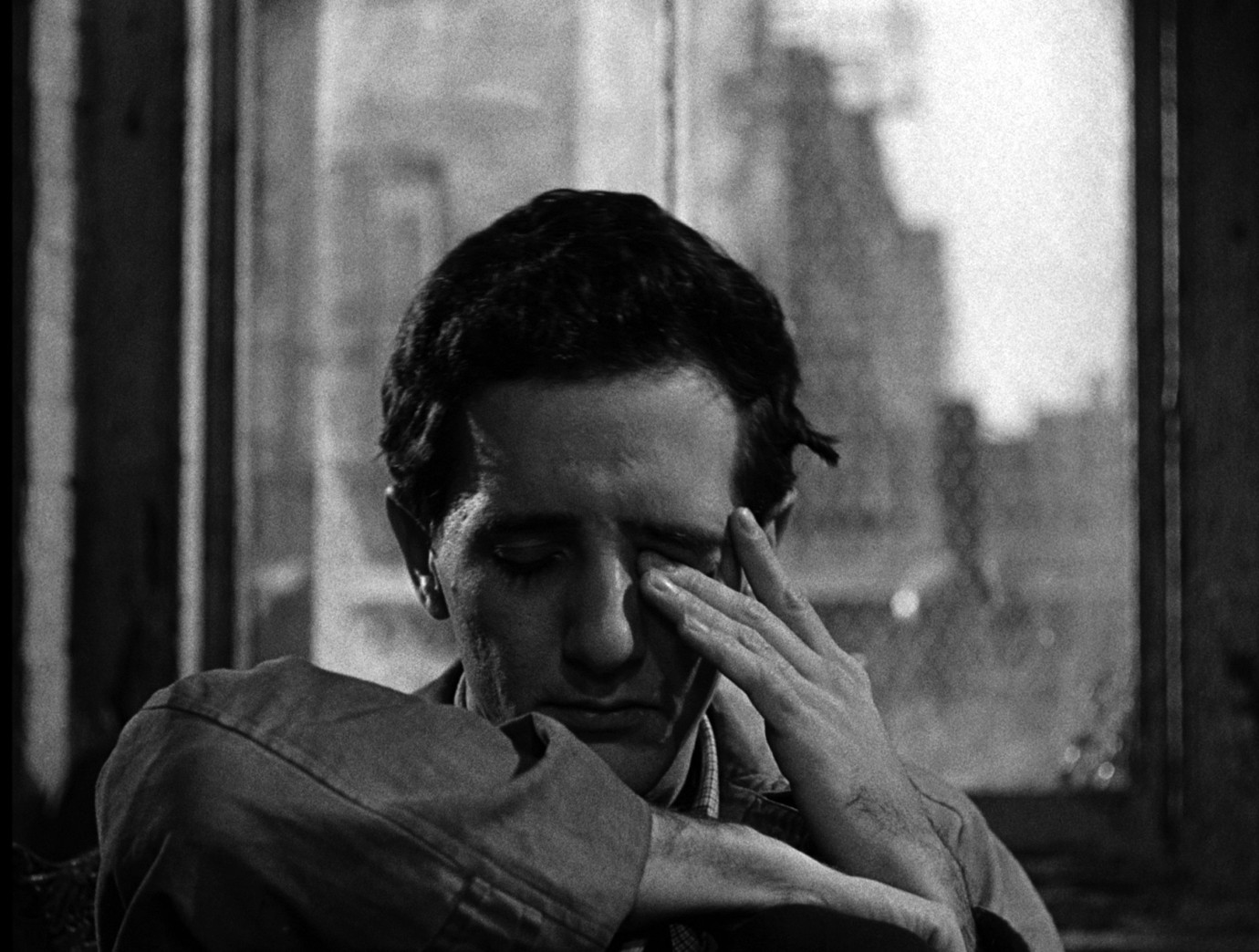

Garry Goodrow

The Connection by Shirley Clarke

USA 1961, Forum

© 1961 The Connection Company © 2012 Milestone Film & Video

Taraneh Alidoosti, Mani Haghighi

Paziraie Sadeh | Modest Reception by Mani Haghighi

IRN 2012, Forum

© Abbas Kosari

Jim Dunn

The Connection by Shirley Clarke

USA 1961, Forum

© 1961 The Connection Company © 2012 Milestone Film & Video

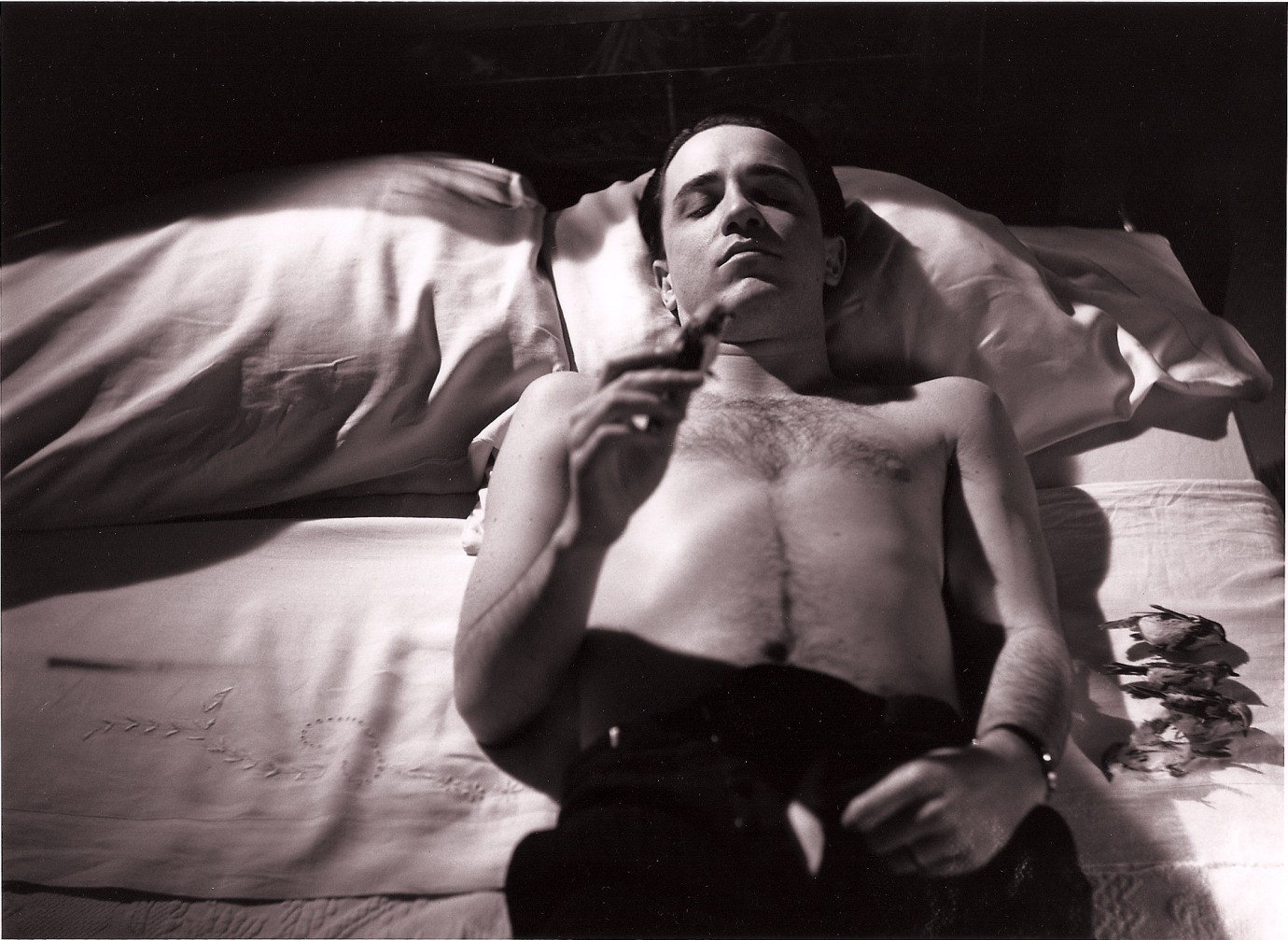

Craig Chester jr.

Swoon by Tom Kalin

USA 1992, Forum

Daniel Schlachtet

Swoon by Tom Kalin

USA 1992, Forum

Lawinen der Erinnerung by Dominik Graf

DEU 2012, Forum

Espoir voyage by Michel K. Zongo

FRA/BFA 2011, Forum

Espoir voyage by Michel K. Zongo

FRA/BFA 2011, Forum

Parabeton – Pier Luigi Nervi und römischer Beton | Parabeton – Pier Luigi Nervi and Roman Concrete by Heinz Emigholz

DEU 2012, Forum

Parabeton – Pier Luigi Nervi und römischer Beton | Parabeton – Pier Luigi Nervi and Roman Concrete by Heinz Emigholz

DEU 2012, Forum

Zavtra | Tomorrow by Andrey Gryazev

RUS 2012, Forum

Zavtra | Tomorrow by Andrey Gryazev

RUS 2012, Forum

Aratama Michiyo, Todoroko Yukiko

Suzaki Paradaisu Akashingo | Suzaki Paradise: Red Light by Kawashima Yuzo

JPN 1956, Forum

© 1956 NIKKATSU Corporation

Die Lage | Condition by Thomas Heise

DEU 2012, Forum

Die Lage | Condition by Thomas Heise

DEU 2012, Forum

Melissa Leo, Keith Leonard

Francine by Brian M. Cassidy, Melanie Shatzky

USA/CAN 2012, Forum

Melissa Leo

Francine by Brian M. Cassidy, Melanie Shatzky

USA/CAN 2012, Forum

Peov Chouk Sor by Tea Lim Koun

KHM 1967, Forum

Peov Chouk Sor by Tea Lim Koun

KHM 1967, Forum

Tsuruta Koji, Awashima Chikage

Kino to ashita no aida | Between Yesterday and Tomorrow by Kawashima Yuzo

JPN 1954, Forum

© 1954 Shochiku Co., Ltd.

Tsuruta Koji, Awashima Chikage

Kino to ashita no aida | Between Yesterday and Tomorrow by Kawashima Yuzo

JPN 1954, Forum

© 1954 Shochiku Co., Ltd.

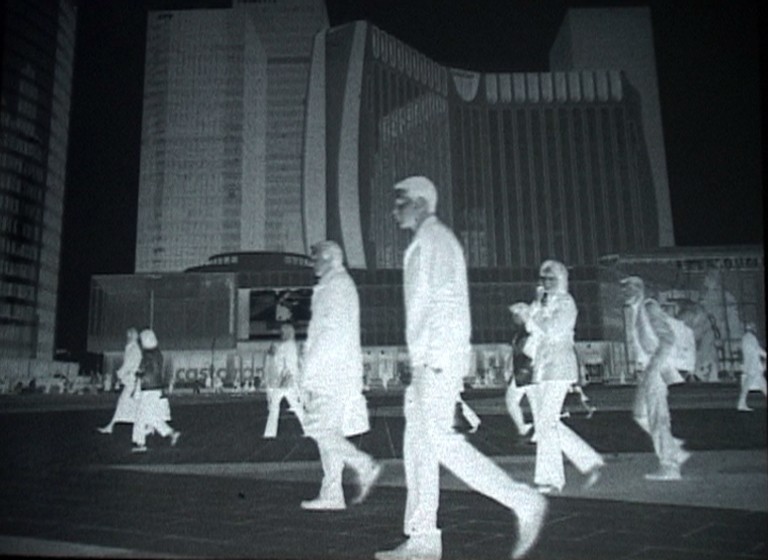

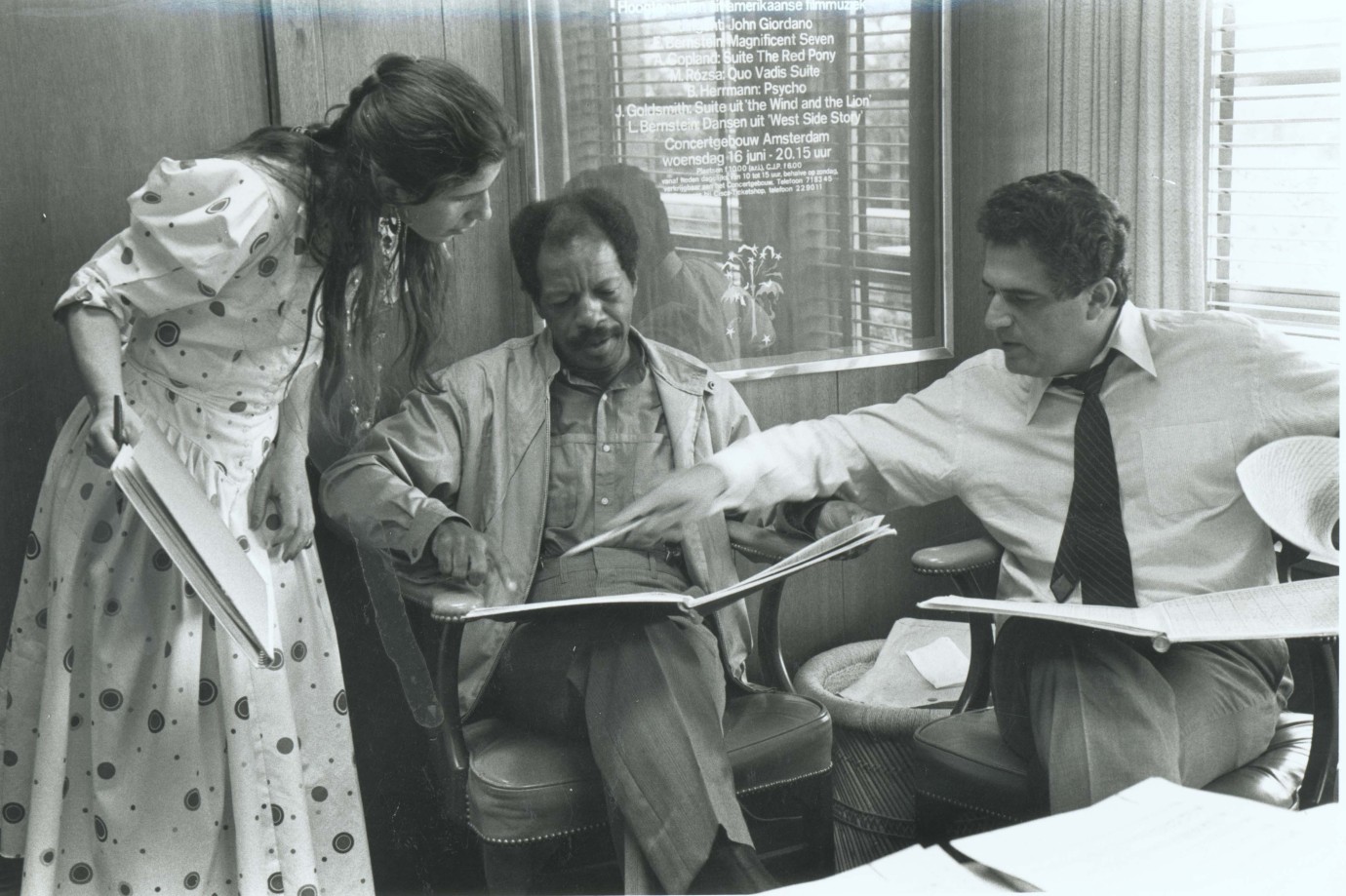

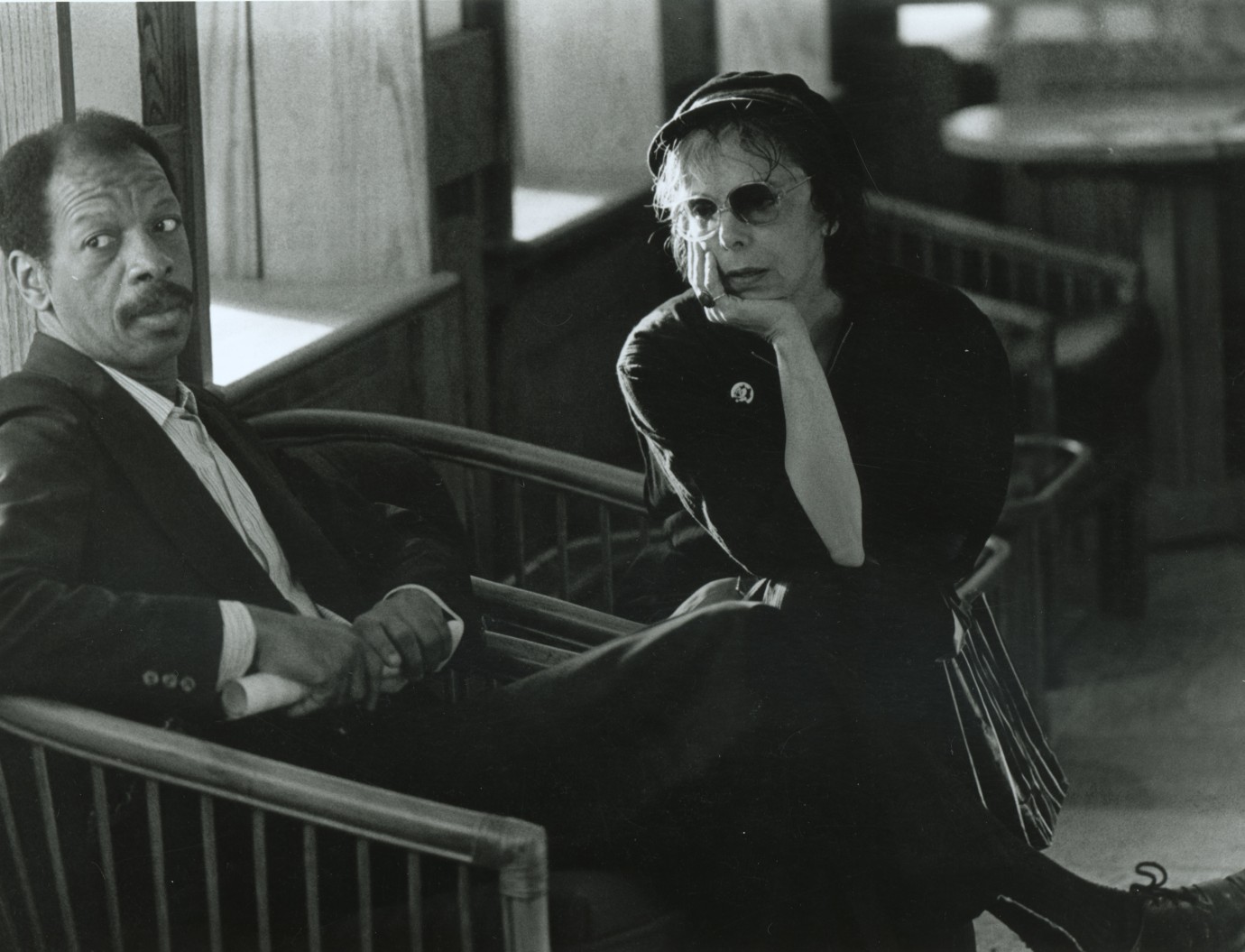

Ornette: Made in America by Shirley Clarke

USA 1985, Forum

Ornette: Made in America by Shirley Clarke

USA 1985, Forum

Sydney Aguirre

Kid-Thing by David Zellner

USA 2012, Forum

Sydney Aguirre

Kid-Thing by David Zellner

USA 2012, Forum

‘Around the world in 38 films’ – that could be the motto of this year’s Forum, couldn’t it?

Our intention is not to provide a comprehensive overview of global filmmaking. I recently printed out a map of the world with country borders and coloured in all the states from where we have films – big white patches remain of course. We have nothing from India, nothing from China, Australia or New Zealand. There are also big white patches in Central and South America and we have only two African countries. It’s not about striving for a proportional distribution of countries based on quotas. Every year we try to place our focus on a different place, wherever something interesting is happening. Geographical considerations play a certain role, but we don’t claim at all to offer a journey around the world.

Last year, generational conflict formed the central theme of the section and is also a focal point in 2012. What new developments have you seen in this area?

The generational conflicts one encounters in this year’s programme take place by and large between adults. With some exceptions: the Czech entry Prílis mladá noc (A Night Too Young) directed by Olmo Olmerzu tells the story of two boys who are suddenly thrown into the adult world. They spend a night with people in their late twenties, early thirties, and see with eyes wide open what lies ahead in their lives.

By contrast, in Sleepless Knights, Stefan Butzmühlen and Cristina Diz chose a protagonist in his late twenties. He returns from Madrid to his home village and considers staying, because his work prospects in the capital are everything but rosy. He encounters a very conservative population, the generation of his parents. That requires a kind of cohabitation of generations that he doesn’t know from the big city.

Formentera by Ann-Kristin Reyels

In the second German film Formentera by Ann-Kristin Reyels, which, like Sleepless Knights, is shot in Spain, a couple from Berlin travels to the island in order to visit the young man’s mother. She lives in a kind of ’68 generation commune. This group has its own ideas about life, which are very much shaped by the 1960s and 1970s. When the young people arrive, conflicts about different conceptions of life flare up. Interestingly, these confrontations end up causing the couple itself to question whether their ideas of life fit together.

The Swiss film Hiver nomade (Winter Nomads) directed by Manuel von Stürler shows a young woman who tends a flock of sheep over the winter French Switzerland with an older shepherd. This form of existence is a great anachronism, the life of an earlier generation, but she consciously chooses it for herself.

In Sekret (Secret), the Polish director Przemyslaw Wojcieszek also addresses the generational question. A young man visits his grandfather in the countryside and confronts him with a story he has heard – that his grandfather may have exposed a Jew who was in hiding during the Nazi occupation. Sekret addresses issues of homosexuality, Jewishness and the whole issue of identity within a rigid Catholic, Polish society.

These are all stories that deal with the responsibility for other generations. And the way that they repeat patterns. Escuela normal (Normal School) by Celina Murga is about two pupils who try out some politics in an Argentinean high school. They copy patterns and models from television – those that are expected of them when they leave school and enter public life themselves. This election campaign is frightening and largely copied.

These sorts of themes run like a thread through the programme, because while selecting the films, we always try to see which ones fit together, to explore where synergies exist. A film programme doesn’t just come together through the best submissions, but gains its character through connections linking the individual works. The selection of films that explore the issue of the right way to live is really diverse at the moment. Because right now familial structures are under threat in many countries and so the filmmakers, the artists address these topics. And generational conflict is a thread that runs through the programme. We tried to place emphases in this range of topics.

The visible and the invisible disaster: Nuclear Nation by Funahashi Atsushi

Blind spots in global awareness

How do these directors approach the damaged nuclear plant, when we don’t actually have any pictures from the inside of the reactor?

The films differ greatly from one another. They all follow their own approach. With Mujin chitai (No Man’s Zone) Fujiwara Toshi enters the forbidden zone around Fukushima – like a stalker in the sense of Tarkovskiy. He captures images of people who have stayed there although they should have been evacuated long ago. Fujiwara reflects this invisible contamination and the way we deal with pictures of disasters, in which we look for the actual image of destruction. The tsunami devastated cities to such a degree that there is simply nothing left. An image reflecting the scale of the disaster is simply lacking. No Man’s Zone is an essayistic film about our desire for pictures of the disaster and the absence of these images. Because in the zone, No Man’s Zone finds mostly beautiful nature, blossoming cherry trees – nothings hints at radioactive contamination.

In the second film, Iwai Shunji explores how one finds new friends after such tragic events, that one suddenly begins to listen to people’s points of view, in which one was previously uninterested. Shunji’s film is called friends after 3.11. March 11 was the day the tsunami swept across the country. With these new friends he talks about Japan, the future, science, the use of atomic energy – on the subject of climate change, there are several very unorthodox positions.

The third film I find very impressive, because it hardly shows any pictures of the tragedy at all. In Nuclear Nation, Funahashi Atsushi portrays the inhabitants of a small town located directly next to the nuclear reactor. Ninety percent of the town was wiped off of the map by the tsunami. The nuclear fallout took care of the rest. Of the 9,000 inhabitants, 1400 are housed in an old school building in a suburb of Tokyo. The mayor, a very tragic character, like a Shakespearean king without a kingdom, tries to keep his community together. Which is of course impossible, because the former residents will never live together in a single community again. They can’t return to their town, and they won’t live together in the gymnasium forever. Funahashi approaches the disaster from the point of view of social structures, without needing to evoke endless images of the flooding or the damaged reactor.

Puos Keng Kang (The Snake Man) by Tea Lim Koun

Another blind spot you shed some light on is Cambodian cinema…

This is really a very exciting opportunity, even if we only have three individual screenings in the Arsenal cinema – a first, necessary step, towards even thinking about preserving these films. Cambodia was the only country in south-east Asia that brought about democracy following decolonization. Sihanouk became president of the country, a man with social democratic values. He modernized the country and was a film-lover who shot many films himself. During his presidency in the 1960s and afterwards in the early 1970s around 300-400 feature films were made. When the Khmer Rouge came to power in 1975, they murdered most of the directors, film technicians and actors. Very few were able to escape with their life, not to mention their films. Which is why only very few of these works still exist. Of course the material wasn’t stored under the best conditions, meaning we had to fight very hard for this small series. For one, we had to convince the directors to show these films. This was only possible with the help of the director Davy Chou, who was born in France and has Cambodian roots. He made the documentary Le sommeil d’or (Golden Slumbers) about the golden era of Cambodian cinema – which is also being screened in the Forum 2012. Finally, we actually managed to bring three of the old films to Germany in acceptable through precarious condition – an adventurous journey.

Did a film infrastructure exist in Cambodia, in the sense of a studio system?

There was no studio system. The films were made under extremely low-budget conditions. The directors were forced to develop their own tricks and their own style. You can see this in the works, which naively produce cinema magic with extremely limited means.

Puthisen Neang Kongrey (12 Sisters) by Ly Bun Yim reminds me of Ray Harryhausen’s early special effects, which were more or less reinvented in this film due to the lack of knowledge of what others had done before. And yet this is what is so charming about the film. Best known is Puos Keng Kang (The Snake Man) by Tea Lim Koun, which is still circulating on the black market in Cambodia as a technically inadmissible 90-minute copy. We show the film in a quality DVD version. Surely this is not the best solution, but nonetheless very enlightening because in reality the film isn’t 90, but 164 minutes long. The Forum is presenting this version for the first time since the era of its production. It is evidence of Tea Lim Koun’s great narrative talent. Young Cambodians know this film either from miserable video CDs or else not at all. The older generation still remembers it. If you like, this is about generations, about a generation that lost the memories of its parents.

Precarious circumstances: Suzaki Paradaisu Akashingo (Suzaki Paradise: Red Light)

An undiscovered Japanese director and an ironic treat

Apart from the Cambodian series, you are also showing three films by Kawashima Yuzo as a Special. Yuzo worked in the Shochiku Studios as the assistant director of Shibuya Minoru, to whom you devoted a small retrospective last year.

These are generations of filmmakers that have yet to be discovered here. Kawashima is hardly known abroad although he made Bakumatsu taiyoden (The Sun in the Last Days of the Shogunate), which is considered in Japan to be one of the ten most important Japanese films ever made. As an artist, he is interested in social change and repeatedly addresses the topic. Bakumatsu taiyoden tells of the final days of the Shogunate before the Meiji restoration. The setting is a bordello, in which various societal forces meet. Suzaki Paradaisu Akashingo (Suzaki Paradise: Red Light) and Kino to ashita no aida (Between Yesterday and Tomorrow) take place in the post-war period, they show the huge transformation that Japanese society went through at that time. Suzaki Paradaisu Akashingo shows a couple that finds work directly on the bridge that leads to the red light district. They are permanently tempted to cross the threshold and return to the red light district, where they were already once stranded. At the same time they want to live a 'respectable' life. The film has some wonderful actors and great black and white cinematography.

Shiny happy people in Ang Babae sa Septic Tank

One more question: The Filipino entry Ang Babae sa Septic Tank (The Woman in the Septic Tank) by Marlon N. Rivera sounds pretty self-ironic in the context of a European festival…

Ang Babae sa Septic Tank makes fun of the truthfulness and authenticity of film in different cultures, because it assumes that most Filipino films are only made for festivals anyway. It tells the story of a group of young people who want to make a truly successful film that will be shown in Cannes or Berlin. The question is what do they need for it? The short answer is: A Filipino film needs a trash heap, poor children on this trash heap, a struggling, hungry, dirt-poor family, and it needs sexual abuse. They write a scene in which all of these elements come together, shoot it and then decide that they need to do it again differently. “Maybe we should turn it into a musical!” We then see the whole thing again as a musical. The main actress, a big diva, at some point cries out: “I want to go to Berlin” which she will of course do. I think that’s a beautiful irony. The films that they’re satirizing really do exist. For my part, after seeing Ang Babae sa Septic Tank I was fundamentally cured, when it comes to a certain type of Filipino cinema!