2024 | Forum Expanded

Distant Connections

In the interview section heads Ala Younis and Ulrich Ziemons talk about ghosts as multipurpose metaphors, 16mm as a resurgent material in experimental film making and what may have surprised them in this year’s selection.

for here am i sitting in a tin can far above the world by Gala Hernández López

Could you tell me a bit about the selection process? What are the criteria used in selecting the films?

Uli Ziemons: That's a difficult question. The field that we are working in – whether you want to call it experimental film or artists’ moving image – is notoriously difficult to define, which is what makes it interesting. Hence, we don't have criteria in the sense that we say a film that uses these particular aesthetics or that specific approach to filmmaking is what we are showing in Forum Expanded. We are looking at a niche within film culture that is informed by the experimental film tradition, but also the way that artists use moving images. All the people in the selection committee are rooted in this world but they might also have specific interests in terms of topics, themes or geographical regions and we all bring these into the discussion. There is no open call for works from Forum Expanded, which is what sets us apart from the other Berlinale sections. We seek out works throughout the year from the networks that each of the members of the selection committee are part of.

Speaking of networks. The press release highlights forms of communities or networks as a recurring topic in this year’s selection. Could you give some examples of these communities and how they are portrayed?

hold on to her by Robin Vanbesien

UZ: This idea emerged during the selection process when we looked at the programme laid out before us. It was something we probably noticed subconsciously but weren't really using as a guideline for curating. The films depict a wide range of communities. What connects many of them is that they are in some way or another precarious because they often face challenges. These challenges might be similar across films. The film In Praise of Slowness by Hicham Gardaf portrays a community of street sellers that struggle to sell bleach on the streets of Tangiers because economic and technological change pushes them out of the market. CERTAIN WINDS FROM THE SOUTH by Eric Gyamfi is a film about a rural community that faces economic pressure and, as a result, is pulled apart because members of the community are leaving, searching for a better life in the more urban centres of Ghana. So both of these films deal with communities that are formed and tested around economic and financial realities. Additionally, for here am i sitting in a tin can far above the world deals with crypto currencies and these very male dominated online cultures where people are enamoured with cryptocurrency and the supposed future that they envision it will enable.

Then there's communities that are built on care, for example, in Robin Vanbesien's hold on to her. The film portrays a community of documented and undocumented migrants, activists and supporters that comes together because a young child is killed by a police bullet in Belgium during a border crossing. They try to find a way to process this case, because the official legal structures will not bring justice to the victim and the victim’s family. Sarnt Utamachote’s I Don't Want to be Just a Memory shows a community that finds ways of processing grief through maintaining and strengthening their friendships.

QUEBRANTE by Janaina Wagner

Ala Younis: In some films, the filmmakers use everyday objects to craft an experience. For instance, in QUEBRANTE by Janaina Wagner an inflatable moon moves across the film and every time it shows up, it looks different. That makes you think about the image you’re looking at. Is the image there? Is it present in the same space as the people in the film? I find this kind of filmmaking inspiring, especially in times when there's either too much film production or none at all. These films are creative and experimental in an interesting way. So I was thinking about communities also in this direction, where filmmakers could work with limited resources or give objects a new use or meaning in their work.

Talking about the materials that are used. Could you explain how in O Seeker the materiality of the 16 mm film influences or enhances the storytelling?

UZ: There are quite a few films in the programme that use 16mm or other analogue film formats, not least because there has long been a resurgence of analogue film as a material used by filmmakers in the experimental field or in the arts. O Seeker is interesting because the filmmaker, Gavati Wad, has a connection to the film lab scene, so it's about using the material with your own hands and processing it yourself. This film has a dreamlike quality, as if we are going through lots of different thoughts in a dream logic sense. And because the texture of the 16 mm material is quite grainy, the film has this almost otherworldly feel to it.

AY: A film shot on analogue film often looks like it belongs to the past. Hence, it can transfer us into another time that is somewhere in between our experiences of the past and our abilities in the present. In Gavati’s film, our sense of time continues to shift, while its images dramatically plant us in the present.

barrunto by Emilia Beatriz

UZ: That's also very much true for barrunto by Emilia Beatriz, another film that uses hand processed 16 mm film. The spatial setting of the film is untethered by this texture and connects spaces that are very far apart – underwater, above water, on earth and far away on Uranus. The aesthetics used here transport this feeling of floating between spaces.

How do some of the films that treat historical topics connect them to the present?

Here We Are by Chanasorn Chaikitiporn

AY: One film that comes to mind is Here We Are by Chanasorn Chaikitiporn. At first glance, it looks like a film that is obviously about the past because it uses a lot of archival footage, but the archival footage can trick us. Strangely, we tend to look at other people's archives as separate from the people themselves. This film reclaims those materials and they become the protagonist’s voice.

UZ: The film makes us aware that history has an author. The “official” archival material is used to tell a very personal story through the eyes of a protagonist who might not be a protagonist of official history because they are just a regular person, so to speak.

Ghost-like beings or phantasmagorias seem to be a recurring topic as well. What makes them so fascinating?

AY: There is more access now to materials that are from the past, to legends, other people's cultures, even to people within one’s own culture because of social media and the ease of communication. There is a lot that artist can deal and work with that does not necessarily have a physical presence, for example legacies, fascinations, fears, haunting ideas and shared sadness. How do you translate something that you do not have a physical trace of? These things can become this ghostly presence in the film. I think this is a symptom of living a life that is multi-layered, fast-paced, and full of contradictions.

UZ: Ghosts are also so intriguing because they are hard to define and we can fill this gap with ideas and metaphors. Ghosts exist in a time outside of our time, and a place outside of ours. Hence, they lend themselves to dealing with things that might make us anxious, that have a certain fear attached to them or are maybe too big to be defined by rationality alone.

detours while speaking of monsters by Deniz Şimşek

detours while speaking of monsters for example explores themes we might defer to a ghost because we are unable to speak about them in other ways because they are just too overwhelming to grasp or too difficult to understand. Not just rationally but also emotionally.

In Grandmamauntsistercat by Zuza Banasińska it's not a ghost, but the witch figure Baba Yaga who becomes a symbol for matriarchy and freeing oneself from an oppressive ideology. But ghosts can also stand for a bigger system that you can't get out of, so they are a multipurpose metaphor. I think that's what makes them so interesting.

What other forms of resistance are shown in the programme?

AY: First of all, resistance to being forgotten or to losing part of history. There is also resistance to colonialism, past and contemporary. Resistance to moving on without questioning progressive legacies of the past. There is resistance to being relegated to the margin. Resistance permeates the films in our programme, it is in the choices of locations, in the choices of images.

UZ: One film that shows that beautifully and poetically is In Praise of Slowness, where the slowness of the title is a way of resisting an accelerating kind of economics. It is a very dignified way of resisting, an “I prefer not to”-way of keeping your dignity and your sense of self through the work you do.

In Praise of Slowness by Hicham Gardaf

Forum Expanded is known for being the Berlinale’s most experimental section. Did you see anything in this year's selection that was completely new to you?

AY: I don't think there's something that we haven't ever seen before, but the combinations are what surprises us. How things, that you think you know, are put together and then appear in a way that you haven't thought of before. Like the man carrying the transparent bottles in In Praise of Slowness. He is wandering through a colourful traditional town selling bleach in these containers. How the film navigates the inner life of the man, his fading profession, and the decolourization that his liquid is promising. When he's going towards the horizon, his bulky composition of bottles disappears, but without glistening in distance. The filmmaker finds his own aesthetic of transparency.

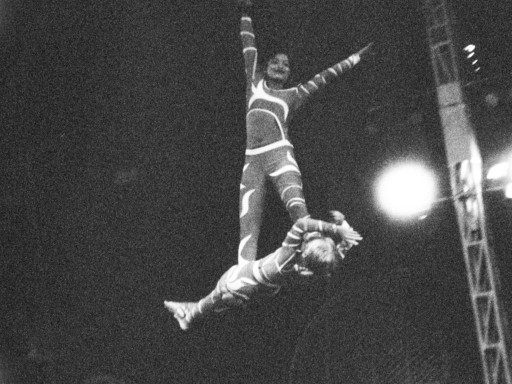

O Seeker von Gavati Wad

Equally sensitive and carefully crafted are the scenes in O Seeker. There's so much beauty in the dark black and white scenes, although you barely see a thing. That is not the first time we’d see a circus, but the way that it's shot and paired with other types of images is special. That's the experiences we'd like to pass on to the audience.

UZ: Many films in our programme deal with this very simple and yet very difficult question of “how do we see the world?”. The premise of Gernot Wieland’s film The Perfect Square for example is that he worked with somebody who trains birds to either fly in circles or in squares. Out of that comes a seven-minute, condensed kind of treatise on how aesthetics shape our sense of the world. The film is intriguing, witty and funny. So these are the things, as Ala said, where it's not so much doing something that has never been done before, but putting your own twist on it and giving a glimpses of newness, like a thought that you haven't had before or an image that you can connect to that thought.

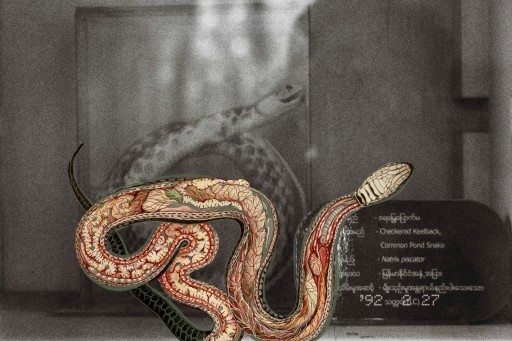

Speaking of connections: How does Prapat Jiwarangsan connect the Yangon Zoological Gardens, Yangon Circle Railway and the Drug Elimination Museum in his installation Myanmar Anatomy?

UZ: The installation looks at these places in relation to the history of colonialism. It explores how these institutions relate to the legacy of colonialism and the structures that were built upon it. Visually, it connects them by reanimating inanimate objects, like still lives of moving nature that we find in museums and dioramas. The installation tries to free them from these structures that they are held in.

AY: You start to also read beyond the things that sometimes go unquestioned when you are looking at a museum display or at a story of an animal from a different time or country.

Myanmar Anatomy by Prapat Jiwarangsan

What is the one key message or experience you hope audiences will take away from this year's programme?

AY: Sadness, loss or displacement are at the heart of a lot of the stories this year. The filmmakers deal with this loss in ways that might be helpful to people who are going through hard times themselves. Either to get stronger or just to find a way to articulate a temporary weakness.

Some films are about recharging. They explore where to find kinship, solace or a space to regenerate and retreat. That’s what we allude to in the subtitle of this year’s programme: “Distant Connections”. How do you link two far-away non-physical points? What could be the intention or the hope that brought them together? This year, the filmmakers are at the heart of the stories they tell. They turn their stories into causes. And that is in itself a strength or a skill that can grow.