2018 | Panorama

The Spirit of Resistance

Since this past summer, Paz Lázaro has been in charge of Panorama as section head, curating this year’s programme together with Michael Stütz and Andreas Struck. The trio succeeds Wieland Speck, who steered the section’s destiny for 25 years. In this interview, Paz Lázaro and Michael Stütz speak about their new roles and the 2018 programme for Panorama.

Kinshasa Makambo by Dieudo Hamadi

First off, the most obvious question: How have you chosen to proceed after the Speck era?

PL: The “Speck era” is a nice way to put it. In fact, everything is new this year. We are 20 years younger than Wieland and work in an entirely different configuration. The Speck era was very focussed on the curator as an individual, one who shaped the identity of the section. Now the three of us discuss the film selection and we have put together a literal panorama for 2018, meaning an extremely rich spectrum of works. We’ve freed up space for ourselves and been able to distance ourselves somewhat from the expectations. That’s why there are fewer films this year in the programme than last year and the programme has gotten more compact.

MS: The discussion process gave us the luxury to be able take our time, to not have to decide right away and to be able to revisit the discussion frequently over a longer period of time. In this way, we were able to see the individual films against the backdrop of the bigger picture that was taking shape. That was an important, organic process for us. It allows the freedom to change one’s own position too. We prodded one another along and were able to exchange ideas in a really fruitful way.

Ex Pajé (Ex Shaman) by Luiz Bolognesi

Crossing Borders

I think this year’s programme really clearly bears your signatures and in my eyes it has been curated very rigorously. The programme testifies to a fragmented, global world and takes a very precise look at particular milieus. This is connected to the theme of “borders” or “crossing borders”. For instance, Ex Pajé (Ex Shaman) by Luiz Bolognesi tells of a place that was once isolated where worlds now collide...

PL: Just like Land by Babak Jalali. Both films show attempts by indigenous peoples to survive in the world of the white man. Their cultural heritage is in the process of disappearing. The main character, the shaman in Ex Pajé, sums it up well: “Back in the day, people paid a visit to the shaman, today they take aspirin.”

MS: The borders and the border crossings can be found here between the original world and a Western-colonized, Catholic one, in which the indigenous people are meant to be proselytized to and converted. Their forlornness is demonstrated for instance by their complete apathy in church. The West forced this religion on them, but it doesn’t mean anything to them. A further scene makes this disjointedness very plain: A woman suffers a snakebite and the shaman attempts to heal her with his natural means. At this point, the film crosses the border into the supernatural.

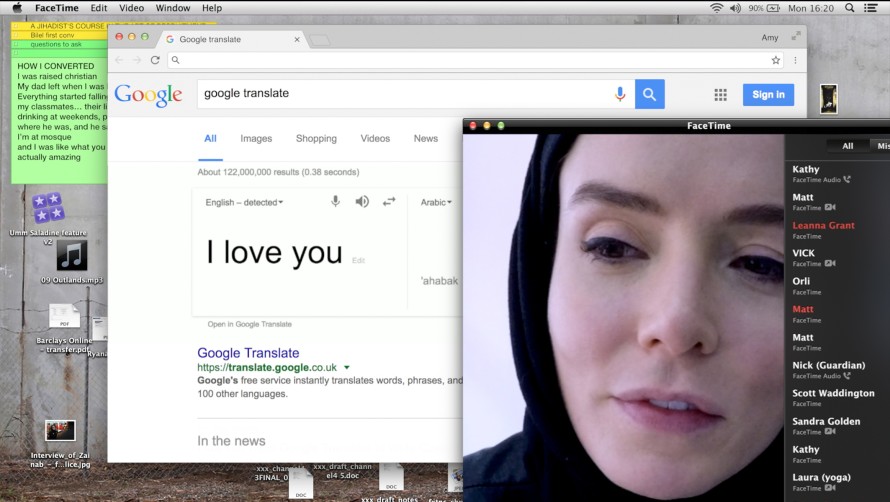

Valene Kane in Profile by Timur Bekmambetov

Digital World

Ex Pajé also shows how Western means of communication – for instance the smart phone – are gaining ground. Timur Bekmambetov’s Profile, which makes exclusive use of screens to tell the story of a journalist who lets herself be recruited to fight for ISIS, shows how pathological the perception of the world through media and especially the Internet can become. Are there more films in the programme that deal with the digitisation of the world?

PL: The subject is very present. Garbage by Q relates the story of a woman on the run because a secretly filmed sex video of her has gone viral online. In Tinta Bruta (Hard Paint) by Marcio Reolon and Filipe Matzembacher the protagonist is extremely dependent on the Internet.

MS: Although he’s able to earn a living in chat rooms, he hides behind his virtual identity, which helps him to overcome his social anxieties. Every communication only happens on a physical level. When he meets a young man online, it becomes the impetus for him to step out of the shadows and open up to genuine intimacy and interaction. That’s the point where complications arise, and he is forced to confront his anxieties. The film’s directors are young and take an extraordinarily contemporary look at their generation.

Susi Sánchez und Bárbara Lennie in La enfermedad del domingo (Sunday’s Illness) by Ramón Salazar

PL: La enfermedad del domingo (Sunday’s Illness) by Ramón Salazar begins with an encounter between a mother and daughter who haven’t seen one another for 30 years. In response to the mother’s question “How did you find me?” the daughter answers: “I just googled you.” So here again the Internet plays a decisive role, if only on a very mundane level.

Až přijde válka (When the War Comes) by Jan Gebert

The Resurgence of the Right and the Decline of the Left

The Internet also seems to play a role for the right-wing extremist paramilitary group in Jan Gebert’s Až přijde válka (When the War Comes)...

MS: Yes. The group very consciously seeks public exposure for propaganda purposes and – in a manner analogous to that of the Islamists in Profile – for recruiting purposes. They are training for a state of emergency, the war between cultures that they invoke rhetorically.

The group appears to be extremely isolated from the outside world, training in the woods. How do their surroundings react to their activities?

PL: With indifference. Society observes and doesn’t do anything about it. A mother drives her little boy to his paramilitary exercise as if they were heading to a football match. This indifference is crucial for the rise of right-wing extremism.

MS: Až přijde válka is an example for nationalism, for the conservative backlash that one can observe on a global scale. Many of the films in our programme show the effects of this way of thinking and what the shift means for women, queer folk and individuals who refuse to conform to the norm in general.

The rise of the right is linked to the decline of the left. Is Hotel Jugoslavija a film that deals with this decline?

MS: The film’s director, Nicolas Wagnières, was born and raised in Switzerland. His mother is originally from Serbia, which means he spent a lot of time there in his childhood. The hotel that gives the film its name, Hotel Jugoslavija, stands for the time before the fall of the Iron Curtain, but it was also used during the civil war and thus becomes a symbol for the changing political eras. Wagnières uses archival footage and voice-overs for a focussed and highly personal reflection on the demise of Yugoslavia.

PL: In interviews, members of the hotel staff talk about the past, but also about the present. They are witnesses to societal and political change. Every now and then, one can sense a certain nostalgia, a longing for that old collective feeling before the hotel was privatised. With the coming of capitalism and civil war, humanity got lost in the shuffle. Under the impression of the decline of the left, the “good old days” quickly become romanticised – this theme can also be found in Je vois rouge (I See Red People), in which the filmmaker Bojina Panayotova questions her parents about their Bulgarian roots. All the way up to the age of 30, Panayotova thought that communism delivered the Utopia it promised and that her childhood in Bulgaria was a beautiful one. When she begins to challenge this belief, she experiences extreme conflict with her parents and the truth about their past comes to light. In both films, the look back occasionally concentrates the energy and prevents any action in the present. Even though looking at the past is of course the prerequisite for looking into the future, as well as being a question of identity, it can also have an inhibiting effect.

The Silk and the Flame by Jordan Schiele

Family conflicts and returning home also play a role in The Silk and the Flame...

MS: US-American director Jordan Schiele, who’s lived in Beijing for quite some time, accompanies a good friend to the countryside, where his family lives in humble conditions. Both parents are physically impaired and are no longer able to speak. This makes communication with the parents very unconventional. The family has developed its own system of symbols to communicate with one another. The Silk and the Flame shows how much the family projects its expectations onto the son. He broke out, left the countryside behind, experienced success and now supports the family. They expect him to get married, although he is gay. That throws him into deep inner turmoil, caught between loyalty to his family and the longing for his own, self-determined life.

Does the film only treat his story on a personal level or does it also touch on sociological categories such as class for instance?

The film dives really deeply into the family microcosm, but it also says a lot about China, about the urban vs. rural dynamic. People move to the city but the connection to their roots remains in place. This lies at the heart of the conflicted nature of a whole society. We have a lot of films on intersectionality in our programme, in which class is discussed and reflected in a conscious way. From Game Girls to Shakedown, from rural Germany in Familienleben (Family Life) to the Argentinian periphery in Marilyn. In the individual films, these things stand for themselves at first glance, but in the scope of the programme there are of course many overlaps and cross-references. This all adds up to a very timely political look at the world.

Game Girls by Alina Skrzeszewska

Resistance

Engaging in resistance is another important theme in your programme in 2018...

MS: Absolutely. Kinshasa Makambo by Dieudo Hamadi for instance is an unflinching treatment of political resistance against President Kabila and examines how individuals feel about resistance, how resistance is organised. Alina Skrzeszewska’s Game Girls portrays an African-American lesbian couple on Skid Row, the USA’s “homeless capital”. The film takes up the subjects of class, race and gender and shows underprivileged individuals who are creating their own space in a self-determined manner and attempting to leave homelessness behind them.

PL: They stay persistent and don’t want to be forced into the victim role. Instead they search for solutions and alternatives. This sort of resistance also plays a role in many other films. There is a lot of energy inside them, they don’t only contemplate situations, they also make a clear statement: “This can’t go on this way, not with us. We’re not going to put up with this.” There is an extraordinarily combative spirit in this year’s films.

MS: In a very introspective way, Martín Rodríguez Redondo’s Marilyn comes to terms with this theme in a coming-of-age story set in the Argentinian countryside. The patriarchal structures there are still very strongly rooted, no one is allowed to step out of line to the left or right. The protagonist is into boys and likes wearing dresses. His desire for self-determination is stifled by his family, which has been living in a precarious situation since the death of his father. The pressure is enormous. A radicalisation takes place on the inside here, one which can neither be articulated nor acted out, since the external world doesn’t approve of it.

Generation Wealth von Lauren Greenfield

A world of internalised coercion also seems to unfold in a nightmarish fashion in Generation Wealth...

MS: The coercions of consumption. But not only that. Lauren Greenfield is also interested in the obsessive relationship with work, beauty ideals or simply money. And in broken dreams too. Each character is broken in their own way and this serves to illuminate the greater human context.

PL: On top of that, she wants to explore the roots of her own obsession with the grotesque excesses of the American Dream, which runs like a common thread through her creative work. As part of looking back to her own origins, she also interviews her own mother. The film is very close to Je vois rouge and Hotel Jugoslavija at this point. Generation Wealth is also very educational: I wasn’t aware that there is such a thing as cosmetic surgery for dogs before.