2017 | Panorama

Getting Away With It

With 51 films from 43 countries the 2017 Panorama is presenting a global cinematic overview. In this interview, Panorama curator Wieland Speck talks about the historical awareness displayed by many films in this year’s programme, "pararealities" from Islamic State to Trump and the vanished lightness in storytelling.

Casting JonBenet by Kitty Green

It appears to me that in 2017 many films are focussing on remembering or the act of remembrance. For example Istiyad Ashbah (Ghost Hunting), Tania Libre, El Pacto de Adriana (Adriana’s Pact) and Casting JonBenet, to name but a few …

In these films the filmmakers take a step back for a closer look. This does indeed run like a common thread through the programme. Many films show the atrocities of the past: for example, the US production Bones of Contention by Andrea Weiss, which sets out to search for the lost bones of Federico García Lorca and uncovers the buried and deliberately repressed history of Spain.

Are the mechanisms of repression comparable?

Yes, I believe so. We live in a country which luckily has a lot of experience with remembering, even though it had to be spurred on “from the outside”. The 1968 generation forced society to come clean. Before that, it muddled through, trying to get away with its past. The success that the world now sees in this German coming-to-terms with the past has been a long journey.

In countries like Spain, the fascist era happened not so long ago, just as in several Latin American countries. Very similar mechanisms were at work in all of these countries, thanks to the influence of the Spanish cultural sphere. And then concepts of a military junta and mass murder were simply imported into the New World. Bones of Contention encapsulates this very well.

In Tania Libre director Lynn Hershman Leeson accompanies Cuban artist Tania Bruguera to her post-traumatic therapy sessions; these were necessary because Bruguera had been detained as a dissident in her home country for eight months. On the occasion of his death Fidel Castro was fulsomely glorified by the Left, but here we can collate this with political reality.

El Pacto de Adriana marks a very personal process of coming to terms with a despotic state. Adriana is director Lissette Orozco’s favourite aunt. During a family visit, the suspicion arises that she had been working for Pinochet’s secret police DNA. To confront the aunt with her past takes a lot of courage. The film was made in spite of all kinds of opposition. It’s very often individuals who address repressed history, because society as a whole does not accomplish this.

Bones of Contention by Andrea Weiss

Another strong film which addresses (false) memories is Casting JonBenet by Kitty Green. It deals with the as yet unsolved murder of six-year-old beauty queen JonBenet Ramsey that was seized upon by a frenzied media and turned into a spectacle. Though labelled as a documentary, the film drifts into the fictional ...

The fictional is the spectrum of memory which never works properly. Much of what we believe to be remembering is not quite true. And that’s not because it’s all a lie. The brain just works differently from how we would like it to operate when we picture historical events. Casting JonBenet shows us many individuals with many different memories of the same event. The film evokes a common memory, even though at the time of the murder these people had few things in common, although they were all present, at least indirectly. Green stages screen tests with all the people who lived in the same place at the time and lets them voice their truths. This method enables her to come closer to the truth because many minds are asked to deal with it. It’s a similar tactic to family constellation therapy, which tries to get to buried, concealed and denied truths. In the final scene, every individual shows us in a joint scene what they believe to be the truth for them.

The technique of physical reenactment and repetition is also employed by Raed Andoni in Istiyad Ashbah (Ghost Hunting) in order to retrace the traumas of Palestinian former detainees of an Israeli prison – and his own repressed memories.

No Intenso Agora by João Moreira Salles

No Intenso Agora (In the Intense Now) seems very experimental in its form. What kind of temporal and visual layers does the film intertwine?

No Intenso Agora is an essay film, something we’ve always liked in Panorama. This form opens up the opportunity to generate a worldview in an artistic-creative manner without having to scatter opportunities for identification. The film starts with a family story in the 1960s. Brazilian director João Moreira Salles was inspired by rediscovered footage shot by his mother in China in 1966 for no particular political reason. However, Salles puts it into a political context by juxtaposing it with May 1968 in Paris, where parts of his family lived, in order to then cross-reference it to the riots in Rio de Janeiro which happened at the same time. There are also many references to Berlin, with Daniel Cohn-Bendit providing the link. The Prague Spring is another issue which is incorporated - a pivotal experience at the time which politicised many people, especially in my generation. Its links to the Prague Spring and 1968 Paris make No Intenso Agora an outstanding contribution to our central theme in 2017, “Europa Europa”. Many films in this year’s programme allow us to retrace where we’re coming from and which direction our journey could take.

Tiger Girl by Jakob Lass

The Pitfalls of Reality

What exactly do you mean by that?

For example, the revolts and the ideas of leftist movements in those days already display all the elements that are now used by rightists. The chutzpah to take to the streets and to loudly demand certain things is leftist chutzpah. Rightists have borrowed this and turned it into a headline for the spirit of our age: “to get away with it” – to make assertions and get away with it. They believe that lying is not so bad if you can get away with it. Meanwhile, reality has withdrawn into “parareality”. Donald Trump becomes the most important person in the world and this simply can’t be true. A large intellectual segment of society has fallen into denial mode and just doesn’t want to believe it. Trump is a master of getting away with it. He utilises a very primitive effect which brings in many votes. Because that is what many people essentially want: to get away with speeding through a red light and so on.

This is also reflected in an interesting way in Tiger Girl by Jakob Lass. A young woman intends to become a police woman but fails the admission exam. Consequently she turns to the private security industry. She meets a young woman - we’re never really sure if she’s a punk or a Nazi - whose anarchy the would-be police cadet finds liberating. Taboos are broken, thresholds are transgressed. Following a climax, the dynamics between them take a wrong turn and the wilder of the two discovers her moral compass. This total role reversal destroys their friendship. An interesting experiment. An emancipation which leads to something entirely horrific. Comparable to red lines that are being crossed by ISIS fighters. The anarchist-leftist bid to overthrow inhibitions is ultimately perverted.

Tahqiq fel djenna (Investigating Paradise) by Merzak Allouache scrutinises the “parareality” of fundamentalist Islamists directly... The starting point are YouTube videos of rather duplicitous sermons ...

In Algeria people are as aghast as they are in our part of the world when they see these sermons – a good lesson for everyone who demonises Islam as a whole. In this film, a young journalist sets off to find out what the male world’s idea of paradise is. She finds 17-year-olds who parrot those idiots from the videos and are actually convinced that dying a martyr’s death is a good strategy for getting hold of “wine, women and song” as quickly as possible. A complete disaster.

And quite absurd. Is this naivety not laughable?

Sometimes, indeed. But that laughter sticks in our throats. It’s absolutely preposterous. In fact they’re basically chasing after the same lies that made Trump the president of the US. You really have to laugh about it, but not because it’s funny. The post-factual has washed away reality. Facts are being contrasted with alternative facts, the difference between reality and substantiality is turning into a different kettle of fish. That’s what we’re currently experiencing. We live in a time that doesn’t want to know what really is, just what currently prevails. “Getting away with it”, quite crudely and simply.

Kaygı by Ceylan Özgün Özçelik

Another film about the disappearance of reality on several levels is Kaygı (Inflame) by Ceylan Özgün Özçelik. It’s a very delicate subject because the film is set in Turkey where at the moment reality is being supplanted by the will of the government ...

Kaygı doggedly follows an ousted and censored Turkish journalist. After her dismissal, she drifts into insanity which is, however, caused by a trauma – that of the concealed violent death of her parents. Here, the past also returns with a vengeance. The vanished don’t disappear, as we’ve already seen in Latin America and Spain.

I regarded God’s Own Country by Francis Lee as exemplary of the possibility of dissolving reality by means of cinema. This is a film that takes a very close look ...

A debut film, told in a classic manner. It shows us the screwed-up world of emotions which we all inherit from our families, but also the possibility of breaking out. A young farmer lives on a sheep farm which he has to manage on his own because his father is too frail. He takes on a hired help, an itinerant labourer from Romania who used to be a farmer himself in his home country. Both discover their passion for one another but the farmer from Yorkshire doesn’t dare to see any future for himself in this relationship. The Romanian leaves and hires himself out on a modern farm with a completely denatured form of agriculture. That’s where Brokeback Mountain finishes – but God’s Own Country goes further.

Vazante by Daniela Thomas

Black History

Another central topic in the programme is Black History. Vazante by Daniela Thomas opens up an historical view. How important is it to approach this subject with an historical awareness too?

Vazante tells the story of slavery in Brazil, and thus of an essential part of Black History and the history of Brazil, even though the film occasionally shifts focus to the white characters. What the world has done to Black people is an incredibly predatory exploitation. Another film on this topic is Joaquim by Marcelo Gomes, also from Brazil, which is screening in the Competition. Brazil was the last country to abolish slavery, as late as 1888. Vazante makes acutely tangible what slavery means and how it worked. We see Black people in chains who can barely talk to each other because they have been abducted from various corners of the world and have no common language. And there’s no possibility of communication with the slave owners either. The mines of Babel, if you will, because Vazante is set against the backdrop of mining – the film’s location is to this day called Minas Gerais.

I Am Not Your Negro by Raoul Peck depicts one of the key figures of the US American Civil Rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s: the Afro-American writer James Baldwin. Does the film succeed in transposing the brilliance of his words into the images?

James Baldwin’s words develop an incredible power in the film – a brilliant New York thinker, orator and writer. An emancipated Black character from the 1950s, a spokesman, and obviously gay. All this redoubles the overall dimension of the character. The film is a magnificent cultural study.

With Strong Island, this year’s programme finally arrives in contemporary Black America, into the racism inherent in the culture. Director Yance Ford tries to delve into the background to his brother’s death, only to encounter a wall of silence. The film chronicles history in microcosm but with great vision; it makes clear why so many Black people don’t even reach middle age – because they are shot dead.

Die Jungfrauenmaschine (Virgin Machine) by Monika Treut

The Story of Berlin

Berlin and especially Berlin’s history are also strongly represented in the programme. Besides two documentaries about electronic music, Denk ich an Deutschland in der Nacht (If I Think of Germany at Night) and Revolution of Sound. Tangerine Dream, Jochen Hick shows us his memories of the city in Mein wunderbares West-Berlin (My Wonderful West Berlin) …

This is a complementary film to his Out in Ost-Berlin - Lesben und Schwule in der DDR (Out in East Berlin – Lesbians and Gays in the GDR) from 2013. With Mein wunderbares West-Berlin Hick looks back on the early days of the gay movement in the 1960s and 1970s. And he does so from the perspective of the time of tumultuous beginnings, before the 1980s. A very nice approach ... Nowadays many people tend to describe the city as being much more exciting today than it was before the Wall came down. To my mind it has rather become more ordinary, both in the West and the East.

Nevertheless, the characteristic Berlin promise of happiness still endures today. Underground heroes such as Bruce LaBruce (The Misandrists) and Shu-Lea Cheang (Fluidø) come to Berlin in order to make their wildest films here - and we screen them. Or take Berlin Syndrome by Cate Shortland, where a young Australian backpacker moves to the city in search of happiness and sexual liberation. Her hopes, however, end in a nightmare.

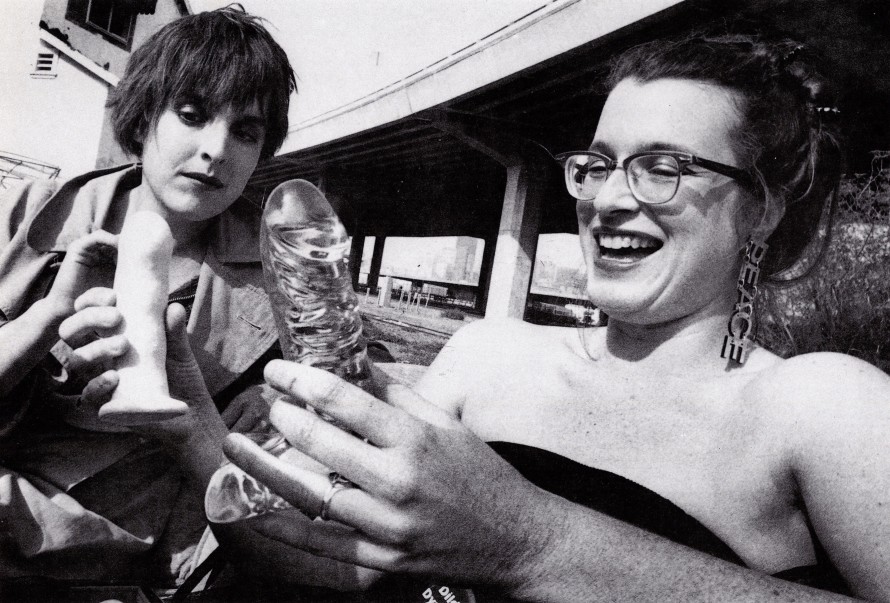

Which brings me to my final question: Monika Treut will receive the 2017 Special TEDDY Award. In her film Die Jungfrauenmaschine (Virgin Machine) from 1988, which you will be screening in honour of this occasion, a naïve journalist sets off towards America where Susie Sexpert shows her – for several minutes – her enormous collection of dildos. Does this lightness in storytelling still exist today?

No, that’s a phenomenon from the 1980s that is no longer to be found in this shape or form today. Professionalisation has restrained us a lot.