2021 | Panorama

Dissonances

In spite of the pandemic-related reduction to 19 films, the selection in the 2021 Panorama is as hard-hitting as ever and, particularly this year, develops an extraordinary power. In this interview, section head Michael Stütz discusses his experiences as a festival maker during the pandemic, radical aesthetics in the selection and a very special return to the Panorama.

Niamh Algar in Censor by Prano Bailey-Bond

How has the last year been for you as a festival maker?

It was characterised by a lot of hope and constant changes. We hoped for a long time that the February date could work out. Then the decision was made that we could go ahead with a reduced programme. We had to have a rethink and make difficult decisions. The workflow was a constant challenge because we had to fundamentally change the way we communicate. We’ve learned to see the positive in these changes, to alleviate the drawbacks with efficiency and to deal with them emotionally. It has affected us as a society, professionally and privately. We’ve had to accept the uncertainty and then make the best of it – as boring as that sounds. What I’ve missed the most, and still miss, is the face-to-face interaction – that can’t be replaced by anything.

Social distancing, the various travel restrictions and working from home during the lockdown has led to an explosion in image consumption for many people. One film which depicts a character who is completely lost in the world of images is Censor. It clearly belongs to the horror genre but develops a tremendous political power.

Yes, it’s a very political film that is ostensibly about a personal trauma. At the same time, the film is deeply rooted in its time and the socio-political situation, and repeatedly makes explicit reference to the repressive Thatcher era. Censor makes the atmosphere of those years tangible, the feeling of isolation and the loss of individual certainties. The protagonist, Enid, is in a permanent state of reflection and, eventually, what she sees day after day appears normal to her: she works as a censor checking the “video nasties” of that time for explicitly violent and sexual content before they are released. She determines what the consumer can and cannot be exposed to. She makes decisions about legitimate and illegitimate images, about what isn’t allowed to be seen because it lies outside of social norms. A particular film triggers Enid’s personal trauma – the unexplained disappearance of her sister – and she becomes more and more immersed in these worlds of horrific images until she is totally subsumed by them. In this respect, Censor is also an apt metaphor for the cinema itself. On an aesthetic level, the film uses an entire phalanx of filters and stylisations to enable us to experience Enid’s descent into the horror film universe and the reflections and shifts in levels of reality. The film is a more than impressive debut from director Prano Bailey-Bond.

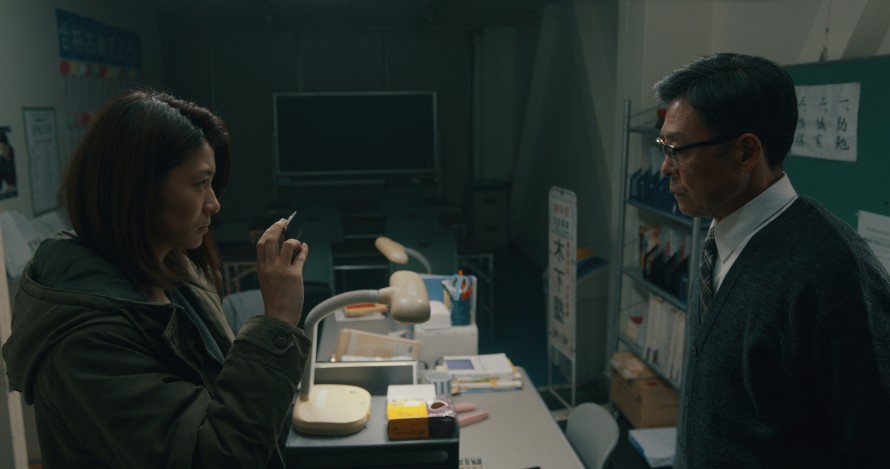

Kumi Takiuchi and Ken Mitsuishi in Yuko No Tenbin (A Balance) by Yujiro Harumoto

The distinction between what can be permitted to be seen and heard and what must be omitted is also the subject of the Japanese film Yuko No Tenbin (A Balance) by Yujiro Harumoto, correct?

Yes, censorship is also a topic there. Young Yuko is making a documentary about a scandal at a private school which ended in a double suicide. Along the way, she’s constantly trying to overstep the boundaries put in place by her broadcaster. That topic is taboo, you shouldn’t go that far. The social code of honour which places such enormous pressure on individuals becomes very palpable. The rule of guilt by association applies – the shame is, above all, to be borne by those left behind by the ones who committed suicide. Yuko contacts those affected and then finds herself increasingly torn between the conflicting priorities of her professional and private perspective. Harumoto’s film is a centrepiece of this year’s programme. He uses authentic images to scrutinise documentary work processes and creates an atmospheric and moving portrayal of Japanese society in the tradition of Hirokazu Kore-eda. Another gem in the programme, which also presents a portrait of a society, is the Turkish film Okul Tıraşı (Brother’s Keeper) by the Kurdish director Ferit Karahan. His film takes us into the microcosm of a boarding school for gifted Kurdish boys in eastern Anatolia. There, we witness the devastating fate of 12-year-old Yusuf and his friend Memo and the indoctrination of these young people by the powerful state educational apparatus.

With Censor and Yuko No Tenbin you have already addressed the difference between what is allowed and what is not. Death of a Virgin, and the Sin of Not Living by George Peter Barbari expresses this dissonance as an inner monologue of the characters via voice-over...

Exactly. Four young men pool their money and plan to lose their virginity with a sex worker. The film broaches this traditional ritual – one which is supposed to underpin masculinity – and counteracts it in a very beautiful and poetically existential way by using voice-overs in which the characters reflect on their lives until the moment of their death. This creates a fuller picture of the characters and the society in which they live. The film breaks with social constraints and allows two worlds – the inner and the outer – to collide. Death of a Virgin is Barbari’s debut film. This year, we again have many first and second works which exhibit an extremely self-confident attitude with their own voice and vision. They stand out not only in terms of content, but also formally.

Théo Kermel and Louise Morin in Théo et les métamorphoses (Theo and the Metamorphosis)

The way Death of a Virgin, and the Sin of Not Living confronts the internal with the external reminds of Théo et les métamorphoses...

Definitely. With Theo, too, the boundaries are increasingly dissolving. Internal and external struggles are a topic present in very many of the films, though in Death of a Virgin the boundaries are particularly powerfully drawn by society and the history of Lebanon. In Théo et les métamorphoses by Damien Odoul, a young man with Down’s syndrome who lives a secluded life in the forest with his father finds himself and his identity in quite a radical way. When his father goes away on a trip, Théo conjures up his Samurai alter ego. By having to rely entirely on himself, he discovers many facets of his existence and his personal expression. The film shows this liberation, which gives free rein to dreams and desires, in a very dynamic way: a continuous, limitless stream without narrative restrictions. As a viewer, it’s easy to go with it because the film has something really touching and liberating about it. At the same time, it opens up a rarely seen perspective.

Self-perception and the creation of one’s own self are also motifs in Miguel’s War, which similarly explores internal conflicts and external obstacles and the influence they have. The protagonist is driven by social pressures to perform. How many identities do we have to keep up in our life? Where are the dissonances to be found?

Miguel’s War by Eliane Raheb

In Miguel’s War there appear to be many dissonances…

The original conflicts, which the protagonist has never really addressed, break out again during the filming. Miguel fled Lebanon 37 years ago, getting away from the war and his complicated family history. He was torn between the demands of a religious, a sexual and a national identity. After his escape to post-Franco Madrid, he created a completely contrary character and lived a life of excess. On his return to Lebanon, he explores, together with director Eliane Raheb, the internal conflicts that still haunt him.

Is the ultimate failure of his escape to Spain due to his past or to what he encountered in Europe at that time?

They presuppose each other, I would say. Miguel had a difficult relationship with his parents, the war left him traumatised. Spain meant a headlong rush into forgetting via excess. The film shows all these sides to a person who has made a great many attempts to come to terms with himself and his own past. Along the way, he piled more and more personalities on top of each other. Miguel’s War collects the fragments of these personalities and discusses them in a very vulnerable way. It’s a process of re-enactment that sheds a lot to light on things but which is still incomplete in the end. The journey is not only physical, it’s also a personal psychological one.

Basmala Elghaiesh uand Bassant Ahmed in Souad by Ayten Amin

The family is an important topic in this year’s selection. Can a line be drawn from Miguel to North by Current?

Absolutely. North by Current is told from the first-person perspective of the artist and filmmaker Angelo Madsen Minax who returns to the home town of his Mormon family. After long years of estrangement, there is a tentative but determined rapprochement. The family history is part of both the problem and the solution. Minax chooses a highly fragmented approach via the different visual formats he uses and thus reveals a splintered family in a splintered society. Like Miguel, Minax escaped, leaving his home to find himself and to live as the person he is. The way back is not easy. The family first has to re-find a common language. North by Current shows this in a disarming and open way. Like Miguel’s War, this film reveals a lot of vulnerability and complex human structures – it’s a huge gift that we, as the audience, can partake in it.

The family appears in almost all the films in one way or another. For example, in Souad by Ayten Amin which depicts the internal and external struggle on the way to finding yourself and your own truth. The pressure to live with multiple identities in order to meet the demands of society and your parents while at the same time wanting to realise your own dreams and lead a self-determined life. Souad first shows this conflict from the perspective of the titular heroine and later jumps to the perspective of her sister and a man with whom Souad has had a purely virtual romance via social media. It is only by this change of perspective that the protagonist becomes really graspable – because she had become lost in the tension between fulfilling the demands of others and her own wishes. The film does this via an incredibly direct handheld camera.

Dirty Feathers by Carlos Alfonso Corral

In Dirty Feathers, the closeness to the protagonists is almost unbearable. Carlos Alfonso Corral depicts people who have fallen out of society. These are sad stories, lacking in hope, but due to the black-and-white aestheticization and classical music, they have a poetic effect. At first, I wondered whether these stories should be shown in this way, but then I thought they couldn’t be endured without the aestheticization...

Dirty Feathers is a documentary journey that takes us to a blind spot within society. The stylistic device of black and white was chosen very deliberately. How would you perceive the film and what it depicts if it weren’t in black and white? I think the aestheticization creates a more neutral and distanced viewpoint.

The film avoids the classic social study because it is so close to these people, giving each of them the space to express their individual personalities, with all of their stories, their dreams and hopes. It’s a wonderful and rare approach that gives viewers valuable impressions, but which cares little about the dramaturgical conventions of documentary cinema. The images are filmed at eye level, Corral uses neither high nor low-angle shots. In this way, he finds a poignant cinematic form for his non-judgmental perspective.

Two works in the selection explore the relationship between humans, nature and technology. Ted K takes on the Unabomber Ted Kaczynski. With the recently observed lack of differentiation between protest movements, Kaczynski would seem to be just as compatible with Extinction Rebellion as with the Trump supporters who stormed the Capitol. How is he portrayed in the film?

Ted K is first of all the story of a retreat and radicalisation, taking a critical look at the technologisation and capitalisation of society. The film is not a classic biopic, it does not psychologise its main character or seek to romanticise him. Instead, the director Tony Stone presents an emotional inventory of the various fragments of Kaczynski. Which brings me back to Censor, because it is also about radicalisation on the quest for truth – the loss of oneself in the world of images or someone’s own ideas of reality.

Elle-Máijá Tailfeathers Night Raiders von Danis Goulet

Night Raiders by Danis Goulet finds a very, very strong image for the struggle between humans and technology at the end of the film...

Yes, a really extraordinary image for remembering your own roots and the dichotomy between nature and technology. Night Raiders is exemplary of many films in the selection because it deals with a classic topic: individual and collective resistance to a political system of oppression. In this case, it’s a rebellion by First Nations people in North America. In terms of genre, Night Raiders is a dystopia and a fable of resistance that is, nonetheless, very close to today’s reality and takes a critical look at the colonial history of North America. In addition, it is a highly feminist film. There are some extremely strong female perspectives this year – for example, in Mishehu Yohav Mishehu (All Eyes Off Me) by Israeli director Hadas Ben Aroya. She negotiates intimacy and vulnerability in three episodes from a playful, feminist viewpoint. In doing so, she explores the boundaries between togetherness, sexual desire and being alone, both in terms of content and on a cinematic level, in a captivating manner.

Is there a film in 2021 that is particularly close to your heart?

All 19 of them and many more! But I’m extremely delighted that we have Monika Treut’s Genderation in the selection. Twenty years on, she’s picked up the thread again that she began with Gendernauts, which screened in the 1999 Panorama. Such a continuation and historiography has a special value in (queer) cinema. Queer narratives have rarely been carried forward and have had to be invented anew by each generation. Twenty years later, these stories are being continued with some of the protagonists and activists from the original film. Genderation is also very much concerned with the changes in San Francisco, which Annie Sprinkle referred to as the “clitoris of the USA” only twenty years ago. As the tech industry has taken over the city, rents have skyrocketed. Some of the protagonists now live in the suburbs, others have completely left the urban space. In these portraits, Genderation almost incidentally tells of a divided country: the USA towards the end of the Trump era.

Katharina Behrens and Adam Hoya in Glück (Bliss) by Henrika Kull

When looking back, do the protagonists in the film get the impression that some things have changed, perhaps even improved, when it comes to queer life?

Some things have taken a positive turn. You can also see that clearly when you look back on the last few decades of the Panorama programme. Much has been achieved. For a long time, Queer cinema was characterised by the male-gay-white gaze but in 2021 we have Monika Treut, Henrika Kull, the transmasculine Madsen Minax and the young Serbian filmmaker Milica Tomovic with her entertaining debut Kelti (Celts). Eliane Raheb’s intersectional gaze prevails in Miguel’s War. A certain sense of self-evidence and plurality have developed and the perspectives are broader, particularly more noticeably feminist. This is also evident in Henrika Kull’s Glück (Bliss): a film about two women who meet and fall in love in their jobs as sex workers. Glück depicts this workplace, which is often misrepresented, in an authentic and direct way. Despite all the progress, however, these films are also shaped by critical perspectives on our past and present, and fiercely point the way into the future.

Are there any key areas in the programme that you would have liked to have focused on even more strongly if you’d had the full scope of films?

Of course, there would still have been plenty of potential to shape and structure the programme further. But our task is now to focus on the 19 selected works and to give them the best possible platform for a successful career. And we have the Summer Special in June to look forward to – when the city can once again become a big screen, both inside and out, and we can appreciate and celebrate cinema in all its diversity.