2016 | Berlinale Shorts

It Has to be Cinema

In 2016, 25 films from 21 countries are screening in the Berlinale Shorts competition. They tackle current political and social questions and include big cinematic images and surreal animations. In this interview, Maike Mia Höhne discusses this year’s selection and the hallmarks of her work as curator.

Lucas Doméjean in Notre Héritage by Jonathan Vinel in collaboration with Caroline Poggi

This year, almost half the selection is formed by films from directors whose work has previously featured in Berlinale Shorts. 2014 Golden Bear winners Jonathan Vinel and Caroline Poggi (Tant qu'il nous reste des fusils à pompe / As Long as Shotguns Remain, Berlinale Shorts 2014) are back with their new film Notre Héritage (Our Legacy). In what way has their formal language developed?

I was impressed by the clarity of the thesis which they discuss in their new film: Lucas is the son of famous porn director Pierre Woodman. He tries to relate to his father and to gain access to love via pornography.

On a formal level, I like their free handling of the material. Their source is the internet, they draw on the aesthetics of computer games, Pierre Woodman’s available films and they stage scenes with knights and ladies – they create their own world in which it isn’t clear where imagination begins, what is real and what is fantasy. And then they take Woodman’s casting photos of naked women on all fours, photographed from behind. And look at them very closely. Until it hurts.

Vintage Print by Siegfried A. Fruhauf

European Cinema History and the Digital World

In this year’s selection reveals two trends. One is an excursion into the history of European cinema, such as in the wonderfully edited film personne by Christoph Giradet and Matthias Müller, or by Gabriel Abrantes from Portugal who, in Freud and Friends, has the courage to show no respect at all to the great heroes.

The other is the video image as a souvenir as in, for example, Oustaz by Bentley Brown from Chad in which he has edited video recordings from his childhood and adolescence into an essayistic diary film in memory of a deceased friend.

You mean, this reveals a generation of filmmakers whose memories are not stored on film but on videotape?

Exactly. For Jonathan Vinel and Caroline Poggi, the aesthetics of celluloid film with all its scratches are, in this respect, completely uninteresting. We are opening the festival with a film which quite skilfully poses the question of how memory can be depicted: Vintage Print by Siegfried A Fruhauf from Austria. A photo on a glass plate, the carrier medium for negatives in the late 1800s, is being transferred into the digital universe via film.

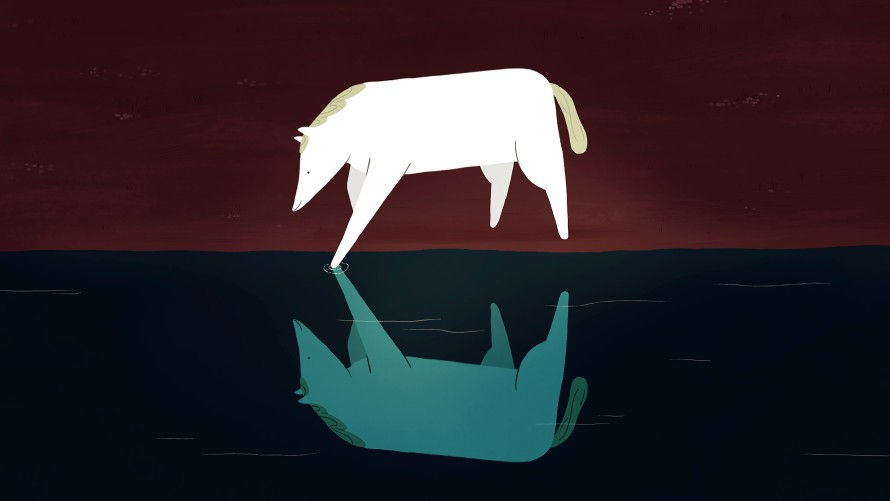

LOVE by Réka Bucsi

You asked earlier about filmmakers whose work we are following: after Symphony no.42 (Berlinale Shorts, 2014) the entire scene has been eagerly awaiting the new film by Réka Bucsi. And here it is: LOVE. Réka states that the word “love” isn’t actually a word anymore. The letters, the shapes, have themselves become an image. And she animates this thesis in her film with surreal situations which seek to express this emotion.

Someone else I must definitely mention in this context is Kazik Radwanski who has already presented three films in Shorts (Princess Margaret Blvd. in 2009, Out in that Deep Blue Sea in 2010 and Green Crayons in 2011) and whose second feature film How Heavy This Hammer is screening in this year’s Forum. In addition, with his production company MDFF he is showing a second film in the Forum: Tales of Two Who Dreamt by Andrea Bussmann and Nicolás Peredas. Formally speaking, Kazik Radwanski produces a very individual narrative cinema, very intimate, without resorting to kitsch.

A Man Returned by Mahdi Fleifel

Special Insights

A Man Returned is a direct continuation of a story – already Mahdi Fleifel’s third film, in which he accompanies the paths of his childhood friends with the camera...

Actually, it’s less of a continuation than the other side of the story. Reda, one of the supporting characters in Mahdi’s film Xenos (Berlinale Shorts, 2014), has returned to Ain al-Hilweh, the biggest Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon, after three years futilely spent attempting to grain refugee status in Athens. A Man Returned considers the question of how it feels to have failed. Why do so many people remain here in Europe even though they are forced to go underground and live without documents? Because it takes a lot of courage to go back.

Being shot in a Direct Cinema style, A Man Returned is very close to its protagonist. The living conditions in the camp are made very palpable. Reda is 26 and totally high. For the past three years he’s been living in Athens, hand-to-mouth and on petty crimes. The scene which made the biggest impression on me is where Reda gives a running commentary over mobile phone footage of hostilities descending upon the camp: he is showing off with his cool poses. It gives a special insight into his everyday life which left me, as the viewer, speechless. And above all else it is about one thing: the wedding and, with it, his salvation from this life.

At the same time the problem becomes apparent that Mahdi Fleifel’s films are all borne by the fate of their protagonists. His success is founded upon other people’s unhappy lives. That is quite a cross to bear for a director.

Bai Niao by Wu Linfeng

It has to be Cinema

Your programming and combination of films also directs the view of the audience. How would you describe the hallmarks of your work as a curator?

Sex and politics. Sensuality and the body. And it has to be cinema. That means, conceived images. As in Bai Niao (White Bird) by Wu Linfeng. You can tell how much thought the director has put into the images and the rhythm by simply looking at the film. Exactly like in Notre Héritage. The protagonist in Bai Niao is HIV-positive. When a distant relative comes to visit, he sleeps with her. During the final seven minutes of the film, tiny shifts are traceable in the focus of the images that cover up morality with a white towel. The border between documentary and fictional material is subverted, making possible a glimpse of the in-between.

Nimit Luang (Prelude to the General) by Pimpaka Towira from Thailand is also very precise in its editing, composition, mise-en-scène and yet it remains mysterious. In the context of Thai history, the film becomes an expression of collective trauma. The past anticipates the future, thus making it impossible for the protagonist to escape in spite of a warning voiced at the start.

My dream would be to watch the programme in full – without any interruptions, preferably without any credits or black in between – simply transitioning from one mood to the next, from one colour to another. For 90 minutes. For 120 minutes. All day short.

Die Unzugänglichkeit der griechischen Antike und ihre Folgen by Gerrit Frohne-Brinkmann and Paul Spengemann

The cinematic appreciation of many of the films in Shorts hinges on an understanding of their cinematic context. Die Unzugänglichkeit der griechischen Antike und ihre Folgen (The Inaccessibility of Ancient Greece and its Impact) presupposes a knowledge of the text recited in ancient Greek.

It’s true that the film may initially come across as puzzling. But it immediately captures the attention with its rhythm and harmonious images. Upon first viewing it, I already perceived the film as a sculpture. During the research process it then transpired that Gerrit Frohne-Brinkmann studied sculpture at the HfBK in Hamburg. Even without knowledge of the text – which comes from Aeschylus’ ‘The Persians’, the world’s oldest surviving play – the film creates a connection with the audience via its images. Via the assembly hall, gymnasium, cafeteria, library, hallways, which everyone has associations with from their schooldays, whether containing humiliation or not.

There’s something similar in Hopptornet (Ten Meter Tower) by Axel Danielson and Maximilien Van Aertryck from Sweden. A really classic short film with a clear experimental design. The camera is pointed towards the platform of a ten meter diving board and immediately conjures up the memory of what it feels like to stand up there. Did I jump? Or not? The tension. The relief. To experience this film communally in the cinema will be a lot of fun. I bet the audience will react to it very directly.

Los murmullos by Rubén Gámez

Concentrated Images

One film in this year’s programme is being screened out of competition. What made you include Los Murmullos (Murmurings) in the selection?

For some years now, I have been including films in the programme which, to me, belong unquestionably in the short film canon. In its time Los murmullos from 1976 marked a caesura in new Latin American cinema. In contrast to his contemporaries, who always understood cinema to also be a weapon against capitalism, Rubén Gámez did not regard editing and cinematography as suitable media for ideological warfare. Instead he took the time to document the conditions of farmers and the influence of the chemical and agricultural industries with calm images. In view of the current TTIP negotiations, this film possesses a downright alarming topicality.

In addition, the form of Los murmullos and its examination of the topic of work spans a bridge across the programme: from Brazil, where we observe in long takes a fisherman at his unceasing, unchanging flow of work governed by the rhythm and power of the sea (Das águas que passam / Running Waters by Diego Zon) to Taiwan, with its migrant workers in Jin zhi xia mao (Anchorage Prohibited) by Chiang Wei Liang. Such workers live in a lawless zone in Taiwan and are almost wholly dependent on their traffickers who pocket just about all their income in the first few years. This is a widespread problem which we can only touch on in Shorts. Chiang Wei Liang also uses quiet images to concentrate fully on a couple and their child, producing a chamber piece in public spaces which in its focus is exemplary of the fate of so many others.

Estate by Ronny Trocker

We are closing the festival with Estate (Summer) by Ronny Trocker. The film is inspired by a photo by Juan Medina which was taken on the beach of Gran Tarajal in Spain in 2006. In the foreground there is an exhausted migrant, in the background people on their summer holidays who are not at all disturbed by what is going on. In the film, the holidaymakers are wax figures frozen in their poses and only the soundtrack is alive. The sound of the sea. Children’s voices. A holidaymaker’s camera lens happens upon a black man who has just arrived. He is the only one who is able to move, who locates himself within the situation and eventually runs off.