2019 | Forum Expanded

ANTIKINO

Forum Expanded is entering its 14th Berlinale year with the exhibition “ANTIKINO (The Siren’s Echo Chamber)”. Section head Stefanie Schulte Strathaus and curator Uli Ziemons discuss a special new exhibition space, echo chambers in art and the possibility of a feminist perspective.

glory by James Benning

This year you’re taking over a new space for the exhibition: the Betonalle of the silent green Kulturquartier complex. Was this a difficult task?

Stefanie Schulte Strathaus: Yes, it’s been a special challenge to work with such a space for the first time. But because, as the Arsenal, silent green is our second home, we haven’t had to adopt a completely unknown location.

How present does the building’s history as a crematorium continue to feel?

SSS: Nobody actually died there. It was a place of mourning, and so of empathy. We’ve been consciously working with the history of the listed building but it’s not getting in our way. And following its renovation, the original function of the Betonhalle is hardly recognisable any more. The complex was built between 1909 and 1912 as part of a free-thinking movement; the Betonhalle was only added after the fall of the Berlin Wall. It was designed to be a morgue with forensic medicine facilities but then, in 2002, the entire crematorium was closed down. Forum Expanded held an exhibition there as early as 2013, just after Jörg Heitmann had bought the building. After that, he and Bettina Ellerkamp oversaw a comprehensive renovation of the complex. Since 2015, our film archive and viewing and project rooms have been housed there.

Diver by Monira Al Qadiri

You settled on the 2019 topic of "ANTIKINO" ("anti-cinema") during a power cut. In addition to the history of the space, suddenly the lights go out - that sounds like a classic scene from a horror film...

SSS: Absolutely. We’d already been having ideas in the direction of “ANTIKINO” but, during the stress of the final selection, we hadn’t actually pinned them down. Then, on the final selection day, there was this power cut. We sat in the dark for a couple of hours and had time to discuss the topic at length.

“ANTIKINO” is also a reflection on Forum Expanded itself. In 2019 we’re entering our 14th year. At the start, we wanted to explore the institutional boundaries between art and cinema but, in the meantime, this debate has faded from the spotlight. Being completely surrounded by moving images as we are today, this dichotomy came to feel increasingly irrelevant. This is also the case for the artists and filmmakers producing the images. Their career histories and means of production might have them identifying themselves either with the film or the art world, but their methods have heavily converged. They’re all attempting to do the same thing: to deal with reality via images. The question of the medium can be negotiated within this process.

The Echo Chambers of Art

The full title of the group exhibition is “ANTIKINO (The Siren’s Echo Chamber)”...

SSS: Historically, avant-garde cinema and modern art have pursued a common interest in a culture of opposition, in reflection and negation. The innovations to which this led have largely become part of today’s canon. We now find ourselves in the type of communal echo chambers that are familiar to us chiefly from social media but which also play a role in real life. We regard the selected works as attempts to escape these echo chambers.

Le Silence des sirènes (Das Schweigen der Sirenen) by Diana Vidrascus

The motif of the sirens is most clearly to be found in Diana Vidrascu’s film Le Silence des sirènes (Silence of the Sirens) which is about depleted images and the difficulties of an actress who finds it equally impossible to identify with the cultures in which she lives and the roles she plays; she falls silent. The Karrabing Film Collective uses the motif of the mermaid: The Mermaids, or Aiden in Wonderland addresses the dying planet against the backdrop of colonialism and extractive capitalism in Australia from the perspective of Indigenous people.

Isn’t it the case that “art” and “cinema” are chiefly categories by which works can be sold?

SSS: Terms like “experimental film” or “expanded cinema” initially weren’t used for marketing purposes. Quite the opposite, in fact: it was about producing work outside the market – although later this itself became a trademark or found its way into the mainstream. Now the visual language of experimental film can be found everywhere: in images of everyday life, in advertising...

I was thinking more in terms of auction houses. “Installation” and “film” are labels around which auction catalogues can be structured...

SSS: In fact, we still find ourselves confronted with categories of organisation when it comes to how institutions see themselves, who has the power of interpretation and market value. But today these categories are much more versatile and thus more difficult to grasp, among other reasons because they seem to be self-generating in the echo chambers. The key question is how artists and filmmakers respond to them. And I believe they’re more flexible than the institutions themselves.

DADDA – Poodle House Saloon by Paul McCarthy and Damon McCarthy

The term “Antikino” / “anti-cinema” also allows you to raise the question of how the images relate to the real. DADDA – Poodle House Saloon by Paul McCarthy and Damon McCarthy chiefly refers to other images via the location – which was already used by Fassbinder and Sergio Leone. Does that not mean the connection to reality is being lost?

SSS: I wouldn’t say that. Most of the works in the programme are very much geopolitically located. They ask about the reality you can find at a specific time in a specific place, also in the form of historical evidence. DADDA depicts media history as actual history. The film takes the violent excesses of pop culture to another level and, in doing so, allows them to become a real experience. It shows how acts of violence have become invisible or intangible when they are translated into media.

Images of the Social

Liqa'lm yadhae (An Un-Aired Interview) by Muhammad Salah makes the relationship between image and experience very clear...

SSS: Liqa'lm yadhae is indeed a very vivid example. Two layers are shown as being separated from each other. The first attempts to portray an ambitious Egyptian man for television. The second unsparingly shows his real life.

Notes to Self is an unusual work for Forum Expanded and the importance of archives. Instead of being preserved, the eponymous notes are burnt...

Uli Ziemons: But we are archiving the video. Christina Battle is playing with the relationship between synchronicity and asynchronicity, how quickly information becomes transient in social media. This makes the work a very good fit for Forum Expanded.

The Script by Akram Zaatari

The work addresses the issue of the inundation by images, particularly in social media. How has this flood altered the status of the image?

SSS: During our initial thoughts about “ANTIKINO”, the overproduction of images and the changed significance of the relationship between images and life indeed played a role. There was a time when a life grew in significance if it was shown on the cinema screen. Today, the mechanism works more the other way round: from an increase to a decrease in value. It’s no longer special to see yourself or another reality on a screen. The explosive power of images has been lost. At a time when everyone is showing images of themselves, it’s no longer a political act. Consequently, this could mean that the subject from which the images originate has also lost its value.

In this context The Script is an exciting work; it focuses on a specific YouTube format, doesn’t it?

UZ: Yes. From the multitude of YouTube videos depicting a praying Muslim father being used as a climbing frame by his children, Akram Zaatari generated a script and stages it in his film.

The Script stages private space in a way that is totally normal today. Did the experimental forms – found in this year’s programme in works such as those by Ute Aurand and Deborah Stratman – to some extent pave the way for making the private public?

SSS: Ute Aurand’s Rasendes Grün mit Pferden (Rushing Green with Horses) very much refers to the private sphere. We’re familiar with the “genre” of diary films in various forms from others like, for example, Jonas Mekas. Over the decades, Ute Aurand has developed her own filmic practice out of this.

Vever (for Barbara) by Deborah Stratman

Vever (for Barbara) by Deborah Stratman addresses and reflects on the problems involved in “diary films”. She holds an off-camera conversation with Barbara Hammer who gave the material to her. Barbara Hammer explains that the footage was shot after a separation on a trip to Guatemala. It was a very personal situation and so she had problems dealing with the material. She found it hard to combine her private life in her thoughts with the place where she’d filmed women unknown to her: she was overcome by the relationship of the images to herself. Subsequently, she put the footage to one side. By then handing the images to another filmmaker – Deborah Stratman – she was able to create a distance. The perspective of another person can see the private from the outside and so work with it. And the question of the ethnographic gaze is brought into play via Maya Deren. The private and the public are negotiated in this film on several levels. For Ute Aurand, on the other hand, the diary is much more about the subjective interior perspective: what has been important in her life, which people, events, places and actions? In this way, she increases the value of a reality which, without her work, would have remained invisible. Therein lies the political and the artistic act.

In view of the subjectivity in Rasendes Grün mit Pferden, Clarissa Thieme’s installation Can’t You See Them? – Repeat. seems almost post-human, as though all human factors in the images are to be cast out...

UZ: Quite the reverse. The film is based on footage shot in Sarajevo while it was under siege. Someone used a camcorder to film militia men crossing a river. The movements of the camcorder have been tracked and translated into a movement executed by a mechanical arm that projects a light cube onto a wall. I would say the human factor is what the film is actually interested in. Who was this person? Why did they move the camera in the way they did?

Jagdpartie (Hunting Party) by Ibrahim Shaddad

Film Histories

You’re showing a small selection of Sudanese films from the 1970s and 80s. What special qualities do these films have?

SS: Each film has its own quality. Al Habil (The Rope) by Ibrahim Shaddad is a wonderful desert film; Jagdpartie (Hunting Party) by the same director feels like a Western. It was filmed in Brandenburg and depicts the hunting down of a black man in the late 1970s. From today’s perspective, this is disturbing in a new way. We make the mistake of expecting no history of avant-garde or experimental film from many parts of the world. But, one way or the other, it was present everywhere - it’s just that the films have frequently not made it into film history. At the Arsenal, we see correcting this as being one of our fundamental tasks.

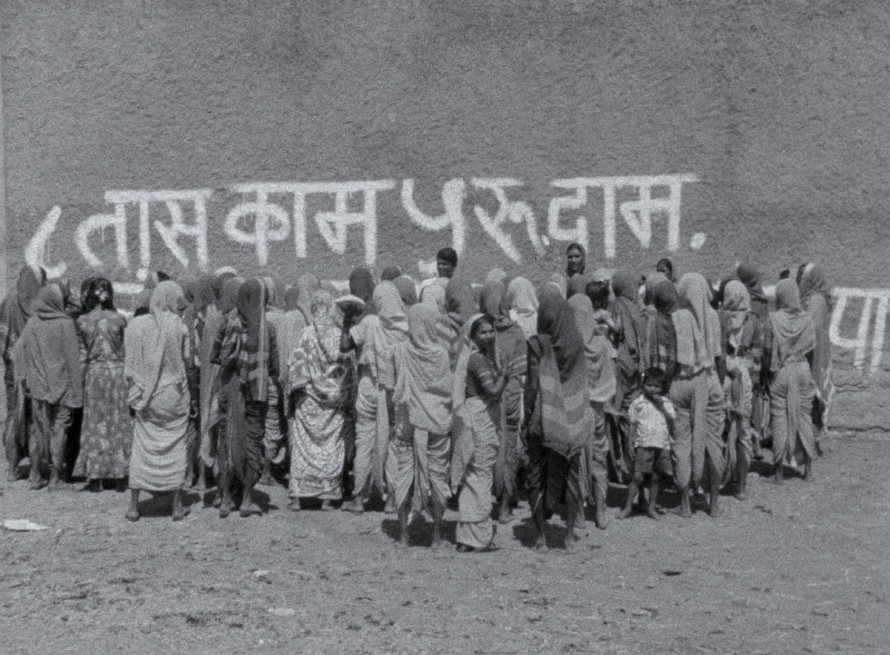

Tambaku Chaakila Oob Ali (Tobacco Embers) by Yugantar

As part of “Archival Constellations” you’re also showing works by Carole Roussopoulos and Delphine Seyrig who, in the 1970s and 80s, used the new video technology to fight alongside the Women’s Movement...

SSS: In our work at the Arsenal and also in the Forum and Forum Expanded, we have always had a feminist objective. Digitalisation has allowed us to de-canonise the canon because we can decide which films should be digitalised first and that, naturally, means expanding film history, including by adding films by women. Many of these films have their origins in a movement, in the context of collectives which were shaped by solidarity and political struggle. That’s also the case for the films from the Yugantar collective in India. These works are not only outstanding examples of political but also feminist cinema. The two are irrevocably linked.

Is it possible to define a female perspective in cinema?

SSS: Fundamentally? There is no female perspective – that’s the wrong question. There’s a feminist perspective, a political one. A perspective against the perspective of power that assigns meaning. This is probably most clearly shown in the film Variety by Bette Gordon which was first screened in the Forum in 1992 and which we are now screening again in a restored 35mm version.