2019 | Retrospective

Searching for their own Idiom

The Retrospective selection committee talks about thematic focus, women’s cinematic aesthetics, and the re-discovery of archival films for “Self-determination. Perspectives of Women filmmakers”.

Veruschka von Lehndorff in Dorian Gray in the Mirror of the Yellow Press by Ulrike Ottinger

They say that women hold up “half the sky”. But in the film production arena, there is nowhere in the world where female directors have anything even approaching equal participation. Despite that, there are an enormous number of films that could be considered for the Retrospective. What kind of boundaries in terms of time period and geography did you draw for your selection?

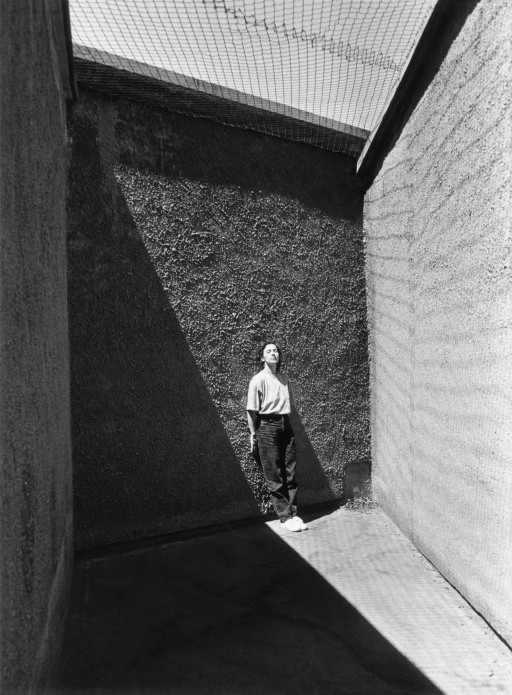

From the start, we wanted to concentrate on women directors whose films were produced in Germany. And we wanted to showcase work from an era when it became, or was, self-evident that women were making films. For a long time, that was not the case. There were exceptions in the early history of cinema, during the Weimar Republic, in the Nazi era and in the 1950s. But we chose the beginning of the women filmmakers’ movement as the starting point for our selection, and that was the late 1960s. We also decided not to go all the way up to the present day. Instead we wanted to concentrate on that initial impetus, meaning the first two generations of female directors in West Germany, East Germany, and Germany after re-unification, which brought us to the turn of the millennium. For technical and structural reasons, we excluded video work, as well as films that existed only in video or Super 8 formats. That was due not least of all to technical problems with screening them. We also selected only films that had had a theatrical release, or were at least screened at a festival, meaning nothing shown only on television.

I Often Think of Hawaii (Ich denke oft an Hawaii) by Elfi Mikesch

During selection, what kind of thematic focus did you decide on?

The word “self-determined” was key for us, as it emerged as the essence of many of the films from those decades. It is closely linked to the pursuit of emancipation in all areas of life that these films show in increased measure, and it’s also usually clearly linked with the life the directors were living at the time. We developed thematic motifs from that starting point, including “work and everyday life” and the reconciliation of the two – a problem that was a key subject for the directors. The same is true of the motif “family ties” or other “relationships”. In general, many of the issues from the early days of the women’s movement are still part of the public debate today, for instance abortion, equal pay, or the shortage of child care. “History” – both of the women’s movement and overall politics – is another focus. Whereby the selected films don’t deal with historical material; they tackle recent history, of the 20th century, or the time when the films were made, between the 1960s and the 1990s. What’s interesting is how much personal history is evident in the films. The women directors are significantly more comfortable than their male colleagues in combining the personal with universal social issues. In the films, it’s also about the “relationship to the man” or men in many conceivable variations. Those portrayals, by the way, are not necessarily always negative or grim.

But you would characterise some of the films as “bleak”?

No, not at all. The term “women’s film” – although that term should be avoided for obvious reasons – is often associated with an attitude of complaint or accusation. But that note is hardly found at all in the films in this Retrospective. The filmmakers are not complaining; they’re looking at conditions and showing how they work – or that they don’t work very well. Their point of view on those circumstances is always self-determined, both in the cinematic and the socio-political sense.

For female directors closely associated with the women’s movement it was more about political content and the direct effect of their work than how they would be seen by history. Are those early “movement films” still accessible today?

Definitely. After a lot of discussion, including with the directors, we made a conscious decision to avoid limiting ourselves to the idea that films by women had to display women’s issues or a ‘women’s struggle’ point of view. It was important to us to take these directors, and what they achieved for cinema in Germany, seriously. So the cinematic quality was paramount for us. Our selection is proof that these films, as it were, “have legs”. They are more than just a product of their time, both in political context and in political perspective. In the companion publication to the Retrospective, there is an essay about the character of the female “flaneur” or woman-about-town – once you realise how interior and exterior spaces are perceived and depicted in the films, and the significance of ‘moving around the city’, it becomes clear that we sometimes short-change the idea of “emancipation”. In our films, it’s about redefining and appropriating the space in which women move and live.

Ulla Lange, Helga Freyer, Edda Hertel, Janine Rickmann in For Women – Chapter 1 (Für Frauen. 1. Kapitel) by Cristina Perincioli

The early films by women in particular were made outside the mainstream, on testing grounds like short films. Did you take that into account?

We see “Self-determined” partially as a sequel to our 2016 Retrospective. “Germany 1966” showcased young German cinema, that arose in opposition to “grandpa’s cinema”. At the time, we could only show the development of women directors in short films. So we are taking up that baton this year with feature-length films, although there are also many short films on the schedule. They include wonderful contemporary documentations on the world of work, like She (1970), Gitta Nickel’s film about the “modern woman” in East Germany, or Heimweh nach Rügen oder Gestern noch war ich Köchin (Homesick for Rügen or Yesterday, I Was a Cook, 1977) by Róza Berger-Fiedler, a portrait of a mayor on an island in the Baltic. In addition to the short film series “work and everyday life”, there is another called “body and space” that is a collection of six experimental and/or animated films.

Did that all come out of nowhere? Or did the directors have role models for orientation?

There were indeed models, both in the West and in the East, but only outside Germany, for instance Agnès Varda in France, and Věra Chytilová in then Czechoslovakia. Especially for the first generation of women directors that we’re looking at, it was crucial that those role models existed. Not only did they chafe under the old cinema, which they rejected, they also benefitted – like their male colleagues did – from the Nouvelle Vague and the “new wave” in Eastern Europe. Those were concepts that were picked up in West and East Germany and helped to renew filmmaking in both countries.

Jutta Hoffmann, Katja Riemann, Nicolette Krebitz, Jasmin Tabatabai in Bandits by Katja von Garnier

Is it possible to pinpoint certain phases and turning points in the further evolution in West Germany?

The shifts in cinematic expression – not limited just to female directors, but in filmmaking overall – are indeed striking. The films from the 1990s are in many ways manifestly different from those from the 1960s and the 1970s, and we want to make that apparent to audiences. Of course, the auteur films from the early days differ from the 1980s’ films, but the evolution of the films after 1989 is even more obvious, as free storytelling starts to morph into more genre work. One early example is the mystery thriller Der gläserne Himmel (The Glass Sky, 1987) by Nina Grosse, which was quite controversial at the time. That development continues up until Bandits (1997) by Katja von Garnier, which exhibits heavy American influences. Angela Schanelec represents a different orientation in Das Glück meiner Schwester (My Sister’s Good Fortune, 1995), which alludes to the future of the “Berlin school” and new forms of storytelling.

Locked Up Time (Verriegelte Zeit) by Sibylle Schönemann

Women directors in East Germany worked under totally different conditions than in the West. What do you see as the differences and the commonalities?

It’s interesting that in 1968, the same year that May Spils’ Zur Sache, Schätzchen (Go for It, Baby) and Ula Stöckl’s Neun Leben hat die Katze (The Cat Has Nine Lives) were made in the West, Ingrid Reschke’s We Are Getting Divorced came out of East Germany. That doesn’t mean that the East German studio DEFA hadn’t let women direct before, but they were assigned primarily to children’s films. It may be a coincidence, but 1968 signalled sort of the starting pistol in both parts of Germany for women to deal with their own chosen subject matter, and to start seeking their own film idiom . In East Germany, women could work within the established studio system, which meant they had sufficient resources. Unless, of course, they ran afoul of the censors, as Iris Gusner did with her first feature Die Taube auf dem Dach (The Dove on The Roof) (1973/2010). It was even worse for Sibylle Schönemann, who was arrested in 1984 because she had applied for an exit visa. She dealt with that issue after the Berlin Wall came down in her brilliant film Verriegelte Zeit (Locked up Time) (1990), by confronting her adversaries from back then and looking for answers.

The early films especially arose from groups of women. To what extent does the Retrospective highlight the lower-profile women who were responsible for cinematography, set design, editing, or financing and producing the films?

We are concentrating – in the discussions around the films as well – mainly on the work of the directors who, in both the West and the East, usually also wrote their own screenplays. But notable camerawomen such as Gisela Tuchtenhagen, Sophie Maintigneux, or Judith Kaufmann are represented as well. The women editors include Angelika Arnold (Berlin – Prenzlauer Berg. Begegnungen zwischen dem 1. Mai und dem 1. Juli 1990 (Berlin Prenzlauer Berg – Encounters between 1st of May and 1st of July 1990, 1990) and Helga Emmrich (Das Fahrrad (The Bicycle), 1982) at DEFA, and from the West, Dagmar Hirtz, who edited Malou (1981) and Die bleierne Zeit (The German Sisters, 1981). The sets for Kennen Sie Urban? (Do You Know Urban?, 1971) are also interesting; they were done by Heike Bauersfeld, who had done the sets for Spur der Steine (Trace of Stone, dir: Frank Beyer, GDR, 1966) and you can actually see the similarities between the two films. Unfortunately, the parameters of the Retrospective are not broad enough to do justice to all the representatives of the industry trades.

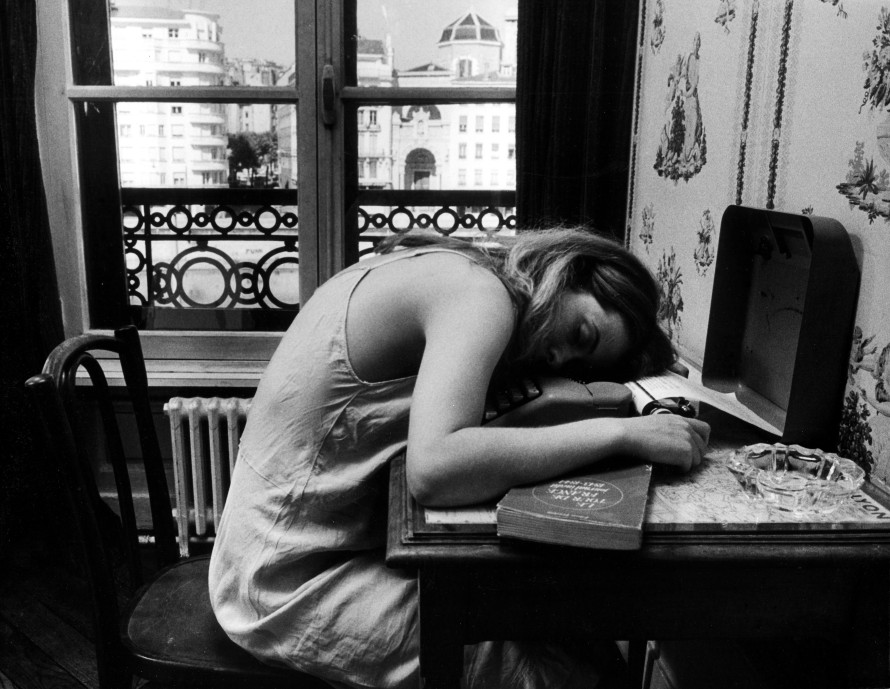

Gabriela Herz, Christiane Carstens und Lisa Kreuzer in Nie wieder schlafen by Pia Frankenberg.

The question of whether there is a specifically feminine aesthetic was much discussed well into the 1980s. Is that question easier to answer now, from an historical distance? Are there forms of storytelling in the films that display an unmistakable female signature or perspective?

Every moviegoer has to decide that for themselves. It’s no accident that Jeanine Meerapfel says, “I don’t make women’s films, I make films.” And of course, when we see a film like Malou, we discover things that we think only Jeanine Meerapfel could have done. But – can that perception be generalised? That will remain a topic of discussion. And that question will be answered differently for different films. Interestingly, when a film fulfils the expectations of a genre, the audience pays much less attention to the question of whether it has a specifically female aesthetic. In those cases, the imprint of the genre is dominant. The expectations of a “feminine aesthetic” are much greater with auteur films. In Nie wieder schlafen (Never Sleep Again, 1992), her film about three women in a re-unified Berlin, Pia Frankenberg was able to direct the way she did because of her closeness with the protagonists. But is that due to a feminine aesthetic or simply more to Pia Frankenberg’s signature?

The German Sisters (Die bleierne Zeit) by Margarethe von Trotta

You are also showing films that were extremely controversial when they were made and sometimes heavily criticised. Should those films be assessed differently from today’s perspective than they were back then?

Yes, that’s true of a film like Die bleierne Zeit (The German Sisters). Margarethe von Trotta’s film was part of an entire series of films at the time that dealt with the subject of the Red Army Faction, the RAF – and not everyone considered it one of the strongest. But when you watch it today, in the context of a differing discourse, you’re struck by things whose significance wasn’t at all evident at the time. For instance, that the child of the “terrorist”, whom she left behind when she went underground, comes into play. That gives the film an emotional quality that is completely missing from the allegedly militant films about the RAF. And it still lends the story a whole other dimension that invokes the future trauma of the following generation. A male director could not have made it that way. It wasn’t really until Christian Petzold made Die innere Sicherheit (The State I Am In) at the turn of the millennium that that particular thread of the story was addressed again.

Rebecca Pauly in Die Reise nach Lyon by Claudia von Alemann

Several of the film titles entered the German language as figures of speech and are still used today. Is it really possible to hope for new discoveries from films that may still be very vivid in the memory of many Berlinale attendees?

In many cases, you can. A film like Claudia von Alemann’s Die Reise nach Lyon (Blind Spot) (1980) about her research on a French women’s rights activist, is regularly mentioned in books on film history. But it was impossible for anyone to actually see it because there were no viable prints, either in Germany or Lyon, where the Deutsche Kinemathek’s new digital version was recently screened to an enthusiastic local audience. It’s a similar story with other films. Basically, most of the films are new discoveries for younger audiences.

How can you ensure that the films selected for the Retrospective will remain accessible?

Thankfully, we received funding from German Films that enabled us to have the films subtitled in English so we can screen them for international audiences. That means that DCPs will be available of numerous films that were almost forgotten because of the lack of viable prints, and they can later be used for screening in Germany and abroad.

The selection committee for the Retrospective “Self-determined” was made up of Rainer Rother, section head and artistic director of the Deutsche Kinemathek, Karin Herbst-Messlinger (co-publisher and editor of the companion publication), as well as Connie Betz (programme coordinator for the Berlinale archival film programme).