2022 | Artistic Director's Blog

On Carole Lombard

Carlo Chatrian was Artistic Director of the Berlinale from June 2019 to March 2024. In his texts, he takes a personal approach to the festival, to outstanding filmmakers and the programme.

Born in Fort Wayne, Indiana, in the Rust Belt, to an affluent family, Alice Jane Peters was actually Californian through and through, having relocated to Los Angeles with her mother as a child. There, at a very young age, she made her big screen debut under Allan Dwan’s direction. She signed her first contract at 16, only to be dismissed two years later, around the same time a car accident almost ended her career. She recovered with a barely visible scar on her cheek and a new spirit, forged in pain and rehabilitation.

Unlike Mae West and Rosalind Russell, Carole Lombard grew up with the movies: first during the silent era, as part of Mack Sennett’s “factory”, and then as a contract player at Paramount after the advent of sound. She had to learn on the spot, in a Hollywood that went through changes at a breakneck pace, swallowing talents and serving up new ones with stunning ease. It’s reasonable to assume this young girl, whose mother had always taught her to be autonomous, seriously committed to understanding how to navigate a jungle of love affairs and real estate deals. She had an extraordinary gift for establishing herself, in terms of communication and contractual power: from her first marriage with the older William Powell to her relationship with Clark Gable, her love life seemingly went hand in hand with her career, as she became more sought after and morphed into a jet set star.

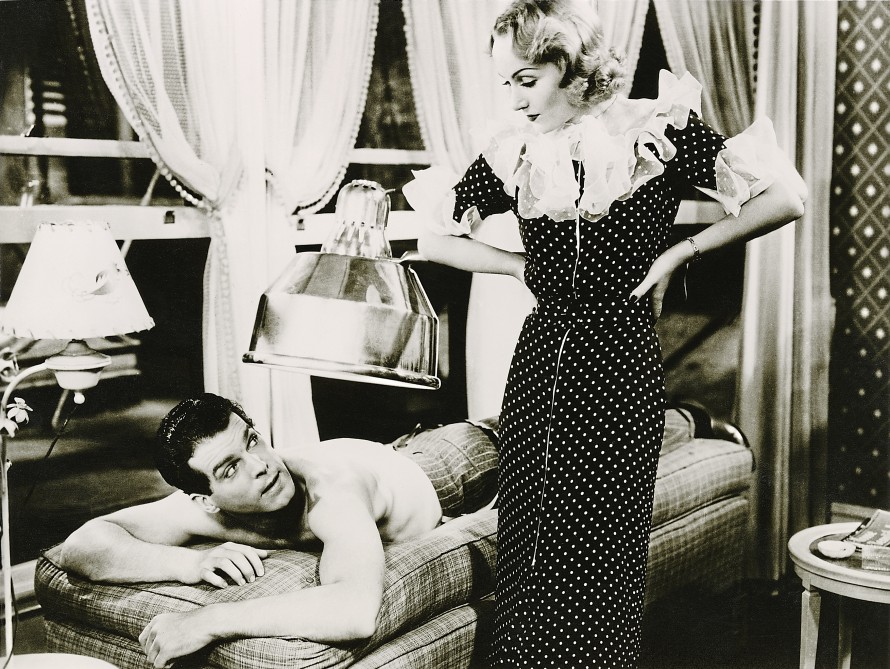

With Fred MacMurray in Hands Across the Table (Mitchell Leisen, USA 1935)

Carole Lombard and her colleagues made their way into a hostile, male-dominated territory. Those who succeeded had talent and determination, not to mention the appropriate cultural and temperamental equipment. Perhaps little of all that remains in the films, but in between scenes that – at least in the early 1930s – are always supposed to focus on the male character, one can see how the women fight tooth and nail to defend the limited space at their disposal. In the fight to escape the wolves of Hollywood, comedy, rather than seduction, is a key element. In comedy, the man-woman relationship shifts, the predatory-sexual instinct weakens, and the two characters are almost on the same level.

In her many promotional photos, Carole Lombard looks like an angel: a finely outlined face, two big, bright eyes and two barely sketched eyebrows, a thin mouth… but appearances are often deceiving. The angel hides an iron will and a peerless knack for assimilation. As seen in the film that made her famous, Twentieth Century (Howard Hawks, USA 1934), the helpless Mildred Plotka quickly morphs into the star Lily Garland. And once she’s made it to the top, she never looks back again. And while her movements are still occasionally reminiscent of the silent era, when women moved to run away from – or towards – their suitors, Lily Garland consistently highlights her desire to be independent, scene after scene.

With John Barrymore in Twentieth Century

Twentieth Century is a larger-than-life film, where normal people’s reality is like the sky in the movie itself, completely absent. The over-the-top acting, biting dialogue exchanges and omnipresent irreverent spirit that plunges the story into madness convey the image of a universe that has lost its centre – assuming it had one to begin with. As Garland says, in a rare moment of intimacy, to Oscar Jaffe, “We are only real between curtains.”

The actor imbues all her characters with the awareness that life is nothing but a great performance and, if one is to play the game seriously, there must be no misconceptions as to where feelings fit. This almost melancholy mood finds its ideal context within the confines of screwball comedy. True Confession (Wesley Ruggles, USA 1937) is a film about lies, nonsense, and disguise; William Wellman’s Nothing Sacred (USA 1937) deals mainly with scams; even when she plays the naïve and stubborn Irene Bullock in Gregory la Cava’s masterful satire My Man Godfrey (USA 1936), Lombard introduces a hint of bitterness.

With Charles Halton and Jack Benny in To Be Or Not To Be

And then there’s Maria Tura in To Be Or Not To Be (Ernst Lubitsch, USA 1942), a summation of an entire career. She acts, deceives, and seduces, falls in love, and keeps two relationships going at the same time, while the outside world is spinning out of control. As is often the case, Lombard embodies a modernity that is both innocent and disillusioned, still falling in love even though she knows all love involves fakery. Despite poses and moves of the time, Lombard was an extremely modern actor, who emphasised the playfulness of acting and managed to pull off moments of great truth. The Gay Bride (Jack Conway, USA 1934) – not a very memorable film – contains a beautiful scene, all about the actor’s face, and naturally the theatre is involved. The stage is where Carole Lombard found the space to express herself freely, to the extent of turning her life into a second set. And in a cruel twist of fate for an actor with such strong ties to comedy, life gave her a tragic, desperate ending.

Carlo Chatrian