2014 | Forum Expanded

The Way Pictures Think

„What do we know when we know where something is?“ is Forum Expanded’s central question this year. Section head Stefanie Schulte Strathaus talks in an interview about the relationship between document and fiction, the location of images and the difficulties of writing film history.

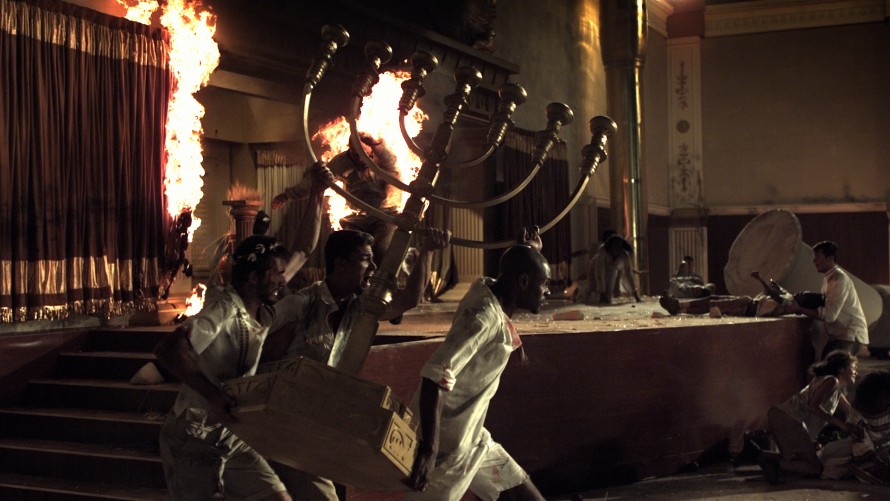

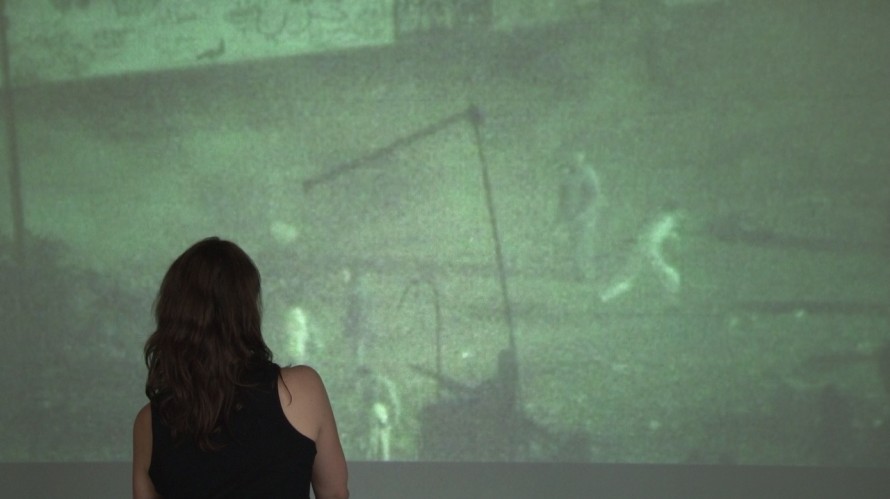

Inferno by Yael Bartana

The 2014 Berlinale has put an emphasis on documental forms. Do you think it still makes sense today to make a categorial distinction between fiction and documentary?

Today there’s an understanding of cinema that doesn’t see fictionalisation and documental practices as opposites, but that emphasises the dramatization in reality, or that recognises dramatization as an image of reality. But it’s still important to refer to the documental as an expression of rumination on cinema’s relation to reality. Filmmaking is an attempt to translate real experience into an aesthetic form. That involves a process and as such, is never congruent with the experience itself. The starker the difference between the two is presented, the more it might seem like a fictional film, but the more documental it becomes, because the mediality is visible. Forum has never drawn a clear line between documentary and fiction film, but I’m in favour of encouraging documental activity. In many respects, cinema as an aesthetic experience is still reduced to the fiction film.

With regard to the blending of documentary and fiction, have cinematic strategies changed, or our perception of them?

Both. But reflection on the documentary has a long history – both in practice and in film criticism and theory. The audiences of today might be more experienced and therefore more open, which means the filmmakers are freer in their use of performative strategies, dramatization levels, cinematic and aesthetic concepts – without having to fear that the film won’t be recognised as a documentary. By now we’re all aware that a documentary isn’t made by simply pointing a camera at something. The activity is a mediating one that carries responsibility, but also a great deal of creative flexibility.

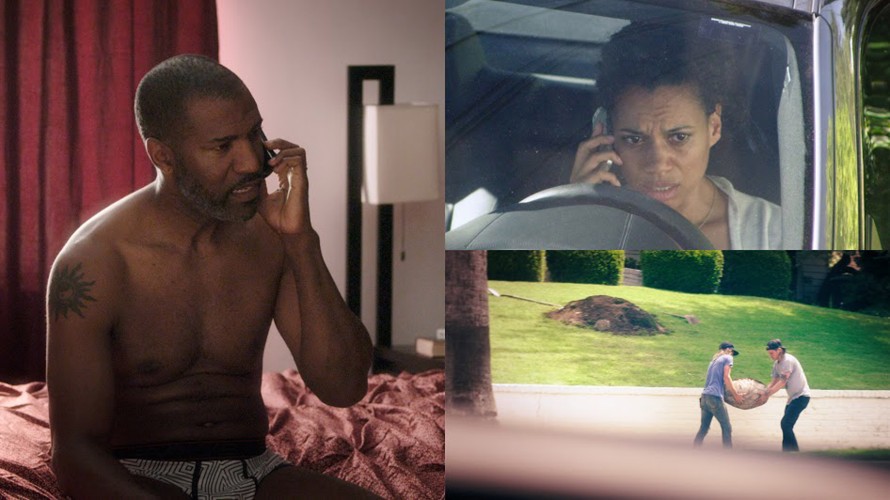

Everything That Rises Must Converge by Omer Fast

Could you illustrate that using the film Everything That Rises Must Converge by Omer Fast as an example?

Through the use of a split screen, different rooms are shown simultaneously on one surface to demonstrate that there is never just one view, that there are always worlds parallel to your own, and that these worlds are inseparable regardless of documental or fictionalising technique. The relationship becomes more complex in Dani Gal’s Wie aus der Ferne (As from afar), where Nazi-hunter Simon Wiesenthal meets Hitler’s architect Albert Speer. The two did actually meet, but knowledge of what actually happened when they did is limited. Dani Gal relocated the meeting to a film set, fictionalising it, because the event is only as representable as our ability to imagine it.

We have multiple examples of this kind. Inferno by Yael Bartana transforms the currently progressing reproduction of the Salomon Temple in Brazil - and its destruction - into a Hollywood action film that she calls a "pre-enactment". 23rd August 2008 by Laura Mulvey is another example. Since the 1970s, she’s been trying not only to write film theory, but also to implement it cinematically – in other words, to capture theory in images. Now she and Mark Lewis have made a film on Faysal Abdullah, an Iraq native living in London, who tells the story of his brother, an intellectual in Iraq. Like many, he went into exile in the 1980s. Later, when he wants to return, he is murdered. 23rd August 2008 poses the question of how to cinematically represent the experience of a government that displaces and murders, and chooses the form of direct narration into the camera, a technique we’ve been familiar with since Lanzmann’s Shoah, if not before. The boundaries between dramatization and documentary are absolutely fluid; the way performance is used in documentaries as an element of style makes it an extension of cinematic documentation.

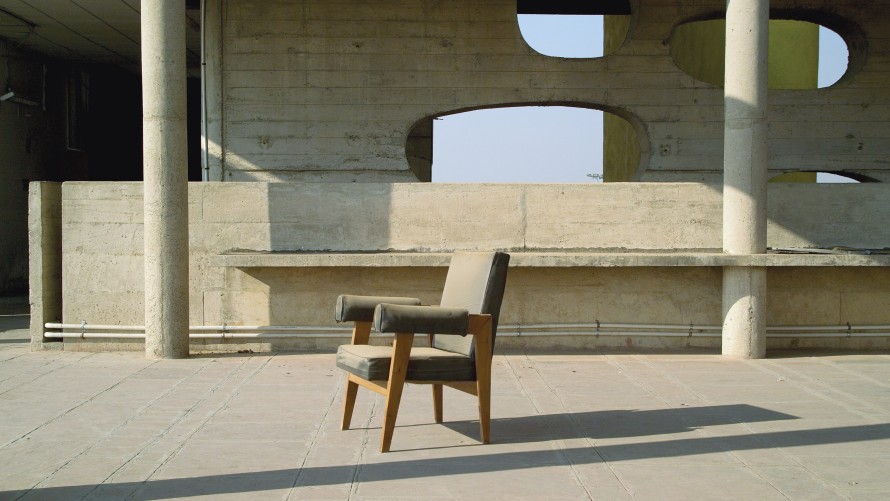

Provenance by Amie Siegel

The renaissance of the mid-length format

You said in your press release that the mid-length format is currently experiencing a renaissance. Why?

Because that’s truly our impression. A length of 30 – 60 minutes isn’t suitable for the theatre and often doesn’t stand a chance for that reason. We got the impression during this year’s screenings that there’s a lot of experimenting going on in that format. Beyond the default lengths lies a freedom that lets film and art meet in an almost laid-back way. And for the films we selected, it seems to be just the right amount of time for the realisation of their makers’ political and aesthetic projects. Maybe that says something about the times we’re living in: contrary to the fast-paced nature of the media, but not reducible to the length standards of only one cultural arena – that of the cinema. So we decided to make short programme sets and treat the films as if they were feature-length, which leaves time for longer and more intense discussions after the screenings: The film might have been just 30 minutes long, but it is a complete and self-contained work, worth being watched and talked about. It’s an experiment; we hope it’ll work out, oftentimes you have to do things like this more than once before they take root. The exhibitions took a few years as well.

Part of the group exhibition: Afterimage by Clemens von Wedemeyer

The film locale

This year the group exhibition is taking place in the church space of the former parish hall ST. AGNES. What challenges does the space bring with it?

The church is a challenge because it has a certain connotation and specific architecture. The acoustics are very particular and we’re dealing with a very large space, not a lot of smaller ones like last year at the former crematorium in Wedding. We didn’t select the films according to whether they fit the space thematically, we paid more attention to how they come across in the space, how they work together. But what does connect the works is a basic debate on the locatability of experiences – the title of this year’s exhibition is “What do we know when we know where something is?”. The question isn’t just posed within the works, it’s also posed within the location of their presentation.

The location of cinema is your focus in 2014. Why are you asking this question right now?

On one hand, it’s a question very specific to Forum Expanded. We’ve been in so many places in the city - galleries, museums, public spaces, the Liquidrome. And everywhere we went, we learned how the inner logistics of that place worked, but also how the presentation of our programme in that space was perceived from the outside. That’s reflected in the discussions on the relationship between art and cinema – the boundaries of which are the home of Forum Expanded – two things that are always attached to specific location categories, to the question of setting. Where does something come from and where do we present it? Is it from the world of film, or the world of art? Do you see it in a theatre or in an exhibition space? The question of setting plays a big role in the definition of cinema. At the same time, the question of film attribution according to nation-state and region is a big issue in light of the many co-productions we have today. There have been massive changes with regards to "world cinema", historical and political shifts have led to alterations of perspective, interpretive authorities are being challenged. The view of experimental film cinema is shifting, for example from the Western world to countries that were barely on the experimental film map up to now, if at all – the Arab world, Africa. For me, this entails either using experimental film as a historical term and looking for a new vocabulary to describe contemporary cinema, or assigning new meanings to old words.

The Zoo Palast is once again a Berlinale venue. The cinema’s self-description includes the following: “In architecture, atmosphere and service, the new, carefully restored Zoo Palast is reminiscent of the great age of film theatre.” Is this kind of concept a model for the future?

Loss always generates feelings of nostalgia, but also creates room for possibilities. Even we had to learn that certain things truly don’t work in exhibition spaces. In leaving the cinema, you can better understand the function of the location. In that respect, I can see a certain cinema renaissance emerging, maybe even amongst those who have tried to move film to the exhibition space. First and foremost, cinema entails an entrance into a time-space structure. We learned how important that is in our exhibitions. You can’t just put a projector somewhere and fire it up. But that doesn’t necessarily mean that a film exhibition has failed, or that films can only be shown in cinemas. But every exhibition space must first be transformed into a cinematic venue, with consideration for the individual film artworks. The space-time experience can be created anywhere, what’s important is that for a certain time, the viewer is provided with that realm of experience.

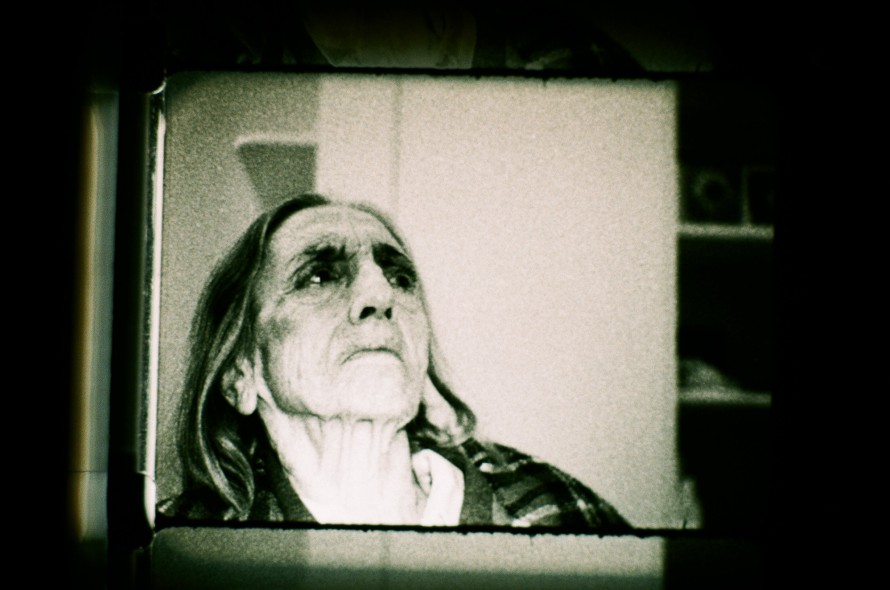

Nec Spe, Nec Metu by Friedl vom Gröller

The invention of film predates the invention of the cinema. Are there any historical presentation practices that could be revisited today?

The realm of experience did exist before cinema as a venue came into being. There was a greater openness towards the possibilities for a cinematic gathering than in later years. We can certainly learn from that. Cinema has to open itself up again as a space for ideas. But that’s easier said than done, given the market interests – from distribution to festival to appraisals in cinema, TV, on DVD and the Internet. The chain of exploitation won’t work in the long run.

One of film’s central locations is the cinematheque with its archive. The Arsenal is working closely together with the emerging Cimatheque in Cairo, and there’s a podium discussion planned for the festival. What challenges does a contemporary film library face today?

The Cimatheque is set to open sometime this spring, and grew from the idea that cinematic innovation and the development of regional cinema need a space for debate, for new thoughts on film history and ways to change it. There’s a need for production sites as well as presentation sites, things that don’t exist there for independent cinema. It’s comparable to the founding of the Freunde der Deutschen Kinemathek, but it’s not a repetition of what happened in Berlin in 1963. Contemporary discussions in Egypt take place in an entirely different environment and must meet both local and Western demands. In talks with our partners in Cairo, we often experienced situations in which questions that we posed were reflected back at us. Their answers told us that the questions we asked were ones we should ask ourselves. It’s an exchange that we all profit from immensely.

Rainbow's Gravity by Mareike Bernien and Kerstin Schroedinger

A Cinémathèque is traditionally a place that wants to give cinema a home, that wants to care for it, present it, provide access to it. A place that takes on the task of showing films that otherwise would go unseen. It creates encounters, opens possibilities for discussion, and connects the present with the past and the future. And it opens our view of the world. The question of what that means in a time where film reception is being constantly decentralised arises naturally. In this situation, a cinémathèque gains more meaning through its role as a go-between, and must position itself accordingly, because the requirements have changed dramatically: What do we know, when we know, where something is? When we see a film in the film world or the art world, or when we have localised it in some country on Earth, we think we know something about it because we know something about its environment. This knowledge is crumbling. But it’s not about replacing it with something else, it’s about looking at the ways and means of producing knowledge – in this case, with cinema – in a new way. That’s where a cinémathèque should start in this day and age.

From behind of the monument by Jasmina Metwaly

Pictures that think

You’re presenting an award for the first time in 2014, the Think:Film Award…

The term Think:Film comes from two thought movements: We think about film, and at the same time, film is a form of thinking. The expression is an attempt to offer an alternative to the historical term of experimental film. When we talk about experimental work today, we mean something different than we used to. The Think:Film Award is a cooperation with the Allianz Cultural Foundation and will recognise a work that generates thought processes about the medium, through the medium, and in doing so, critically examines geopolitical contexts and expands the scope of aesthetic experience. The artist will be invited to Berlin and Cairo to present the work in both places.

Egypt is one of the programme’s focuses. What kind of images are produced in an instable political situation, and how can you write history in its midst?

A phase of political upheaval that proves to be difficult and drawn-out certainly demands respectively complex forms to give that experience a voice. The situation in Egypt is so complicated and in flux that reflecting it in film is a big challenge. At the moment you create a product, you end something, you give rise to a homogenous space, and that’s always contrary to the situation, to the experiences there. So it stands to reason that very open forms will be created. In Malak Helmy’s installation Music for Drifting there’s no image to be seen, it’s a straight sound work, which doesn’t satisfy the West’s desire for representations of revolution. It’s difficult to think about alternative images in Egypt if you want to be seen abroad. In Heba Amin’s work, she imagines where the Speak2Tweet messages were sent in January 2011 when the Internet was down. She recorded images in empty Cairo buildings, effectively re-grounding the displaced voice messages. From behind of the Monument by Jasmina Metwaly is an examination of the events in Mohamed Mahmoud Road in 2011. She lives in Cairo but was in Italy at the time. She set up a screen, projected images from the street and made a subject of that spatial distance. In that kind of situation, it’s nearly impossible not to re-organise the relationship between cinema and reality.