2017 | Retrospective

“The Perfect Future is the Most Boring Thing Imaginable”

Section head Rainer Rother talks about the positive aspects of negative future scenarios, an interstellar model in the energy revolution, starfish-shaped aliens and other surprises in this year’s Retrospective.

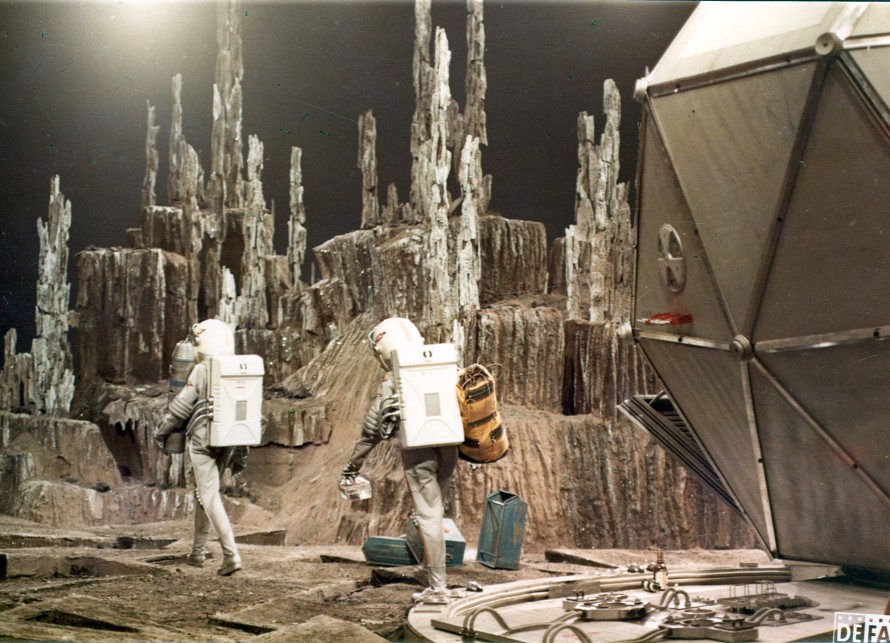

Ikarie XB 1 by Jindřich Polák, Czechoslovakia 1963

The universe is infinite. The Berlinale is not. Through which, by necessity limited, “universes” is the Retrospective travelling?

The Berlinale Retrospective is closely connected to our “Things to Come” exhibition at the Museum für Film und Fernsehen which is exploring the history and motifs of science fiction films and runs until April 2017. The Retrospective thus revolves around two of the genre’s central themes: encounters with the “Other” and designs for the “society of the future”. We have eschewed the third classic aspect of science fiction, space exploration, in favour of these two subject areas. This means that the film selection is not predominated by space operas.

The War of the Worlds by Byron Haskin, USA 1953

What makes these two main topics so interesting?

We are starting from the premise that although science fiction tells a story set in the future, it actually uses this future to negotiate contemporary questions and situations. These socially relevant questions revolve particularly around “How will we live in the future?” and “Which developments could determine our future lives?”. In this respect, science fiction constitutes a continuation or accentuation of tendencies already present in our world. Regarding the concept of the “Other”, however, it is interesting to see that the “Other” is not always depicted in the form of an aggressive invasion as in, for example, the 1950s classic The War of the Worlds (dir. Byron Haskin, USA, 1953). The “Other” can also be a decisive factor in how we define ourselves.

What does this mean with regards to the temporal and geographical positioning of the selected films?

The films selected were made between 1918 and 1998. We didn’t deliberately set this timeframe, it came about in the selection process. Himmelskibet (A Trip to Mars, dir. Holger-Madsen, Denmark) from 1918 is the oldest film in our selection; Dark City (dir. Alex Proyas, USA / Australia) from 1998 is the most recent. This means we have not restricted ourselves to a specific time period although, for example, there was a big science fiction film boom after World War Two, especially of course in the USA. But beyond that we are also looking towards Eastern Europe where we are particularly interested in the future scenarios developed there during the time of real socialism.

Na srebrnym globie by Andrzej Żuławski, Poland 1978/89

And have you come across particular characteristics in the films from the former Eastern Bloc?

Yes, you would think that a society which defined itself as being on the road to “classlessness” would have little need to create alternative future scenarios, because the future already lays clearly ahead. But that was actually not the case in Eastern Europe which instead gave birth to an astonishing number of dystopian future visions.

The title of the Retrospective, “Future Imperfect”, already suggests that visions of the future on the big screen are, in general, not a particularly rosy one. Do sceptical future scenarios make the better films?

Yes, of course! Because narratives of a dystopian nature can be applied much more productively than those set in a future where everything is hunky-dory. In the latter, the potential for conflict, so essential for every good story, is virtually zero. Science fiction profits from doomsday scenarios, negative societal developments and catastrophes which must be or have just been survived. Only then can a story unfold in a popular medium like film which has an emotional impact on the audience. The perfect future is, in storytelling terms, the most boring thing imaginable.

Close Encounters of the Third Kind by Steven Spielberg, USA 1977

Are there nevertheless any films in the selection which project a positive vision of the future?

Yes, there is always the narrative possibility of a happy ending which allows for a positive outlook on the future. For example, Le cinquième élément (The Fifth Element, France 1997) by Luc Besson in which not only the future of the earth but also the entire order of the universe is jeopardised. Now it may seem a bit cheesy that love is the force which averts the end of the world, but within the scope of a science fiction spectacle with Hollywood appeal it is totally plausible. Himmelskibet, the Danish film from 1918, can also be included in the positive visions. In it, humans encounter a peace-loving culture on Mars and love causes a female Martian to accompany the protagonist back to earth to spread a message of peace during the First World War. Close Encounters of the Third Kind (USA 1977) is also interesting in this respect. Here, Steven Spielberg creates a situation which would normally result in a violent confrontation between humans and aliens. But in the end, the hero is presented with the prospect of travelling with the aliens to their home planet.

In this way, the selection also allows encounters of a peaceful kind, which are unusual in cinema?

Yes, to combat the cliché that aliens only ever arrive to exterminate humankind and destroy the world we have a few alternatives on offer that are really beautiful. For example, the wonderful Japanese feature film Uchūjin Tōkyō ni arawaru (Warning From Space, dir. Kōji Shima) from 1956 in which starfish-shaped aliens seek to warn the “earthlings” about an impending collision with another planet.

Klaus Löwitsch in Welt am Draht (World on a Wire) by Rainer Werner Fassbinder, West Germany 1973

Science fiction films are actually, in the main, period drama projected into the future. “Period pieces” often use a historical backdrop to reflect upon their own time. Is this also the case in the Retrospective films?

Yes, absolutely. And sometimes you don’t even need costumes which appear futuristic. We have two or three films in the selection with a science fiction setting which do not find it necessary to turn themselves into period drama. Welt am Draht (World on a Wire, West Germany 1973) is a good example. Here, Fassbinder depicts an apparently near future in the 1970s which, at first sight, feels very familiar and contemporary before it is revealed to be an electronic simulation. Or Na srebrnym globie (On the Silver Globe, Poland 1978/89): this film by Andrzej Żuławski is set in the future but on a planet with an archaic tribal culture which, with its primitive clothing, seems to belong to the past. Its totalitarian traits, however, come across as totally timeless because it depicts universal patterns of the decline of humanity.

If science fiction can be just as much about the present and the past, does this mean technical innovations are not necessarily definitive of the genre?

For the genre in general they are. But those science fiction films which ignore the technical aspects are particularly fascinating. This is more frequently the case in European auteur films than in big Hollywood productions. So in films like the German urban thriller Kamikaze 1989 (dir. Wolf Gremm, West Germany 1982) or the Polish apocalyptical vision O-bi, o-ba: Koniec cywilizacji (O-Bi, O-Ba: The End of Civilisation, dir. Piotr Szulkin, Poland 1985). These are films which display a certain restraint regarding the kind of production values usually employed to illustrate credible future cities. Instead, they concentrate more on the philosophical implications of their future scenarios. Such films are also often dark films; in them, societies reflect upon their fears about the future stemming from their current situation. This is particularly obvious in films which presuppose a nuclear apocalypse like Stanley Kramer’s literary adaptation On the Beach (USA 1959) and the Soviet production Pisma myortvogo cheloveka (Letters from a Dead Man, dir. Konstantin Lopushansky, USSR 1986).

Eolomea by Herrmann Zschoche, East Germany 1972

If the same fears prevailed in the USA and the USSR, are there any differences in the systems recognisable in the films?

One difference can certainly be observed in the 1972 DEFA production Eolomea (dir. Herrmann Zschoche, East Germany). It revolves around a woman played by Cox Habbema who, as a scientist, has the chief responsibility for the entire situation. In this you can recognise a clear difference between the two models of society. In America it took until the end of the decade, until Alien (dir. Ridley Scott, USA 1979) put a woman – the astronaut Ripley, played by Sigourney Weaver – in charge of the controls of a Hollywood spacecraft.

Which means that there are also films that not only reflect the given situation but also trigger discourse?

In this regard the second silent film in the programme, Algol. Tragödie der Macht (Algol. Tragedy of Power, dir. Hans Werckmeister, Germany) from 1920, with Emil Jannings in the lead, is definitely worth a mention. It’s fascinating how contemporary the issues in this film feel today. Especially the energy scarcity and how hooked humans are on “conventional” energy like coal. And how they overcome this addiction with a new energy source from another planet.

At the start, the genre was defined by a great enthusiasm for technology. Since then, a rather more sceptical attitude has spread throughout society. Is this change also present in the films?

Yes, Kathryn Bigelow’s Strange Days (USA 1995) is a good example. Today, virtual reality goggles show that prophecies from 1995 have become reality. You can watch someone else’s life and actually experience it for yourself. This is depicted in the film as quite double-edged. Especially as Strange Days is probably one of the first American films to address the excessive use of violence by the police against black people, which today comes across as a prophesy of a development in American society which has now become a much more present topic of discussion.

Dark City by Alex Proyas, USA / Australia 1998

Science Fiction has also always been a testing ground for cinematic technological innovation. Which films in the selection were in this sense avant-garde?

Blade Runner (dir. Ridley Scott, USA 1982) has unquestionably been style-defining as the model of a future city. Ridley Scott was surely inspired by Metropolis but he himself has inspired an entire succession of films, above all with regards to what a globalised world would look like in an imperfect future – with the vision of an admittedly multicultural society which is sometimes also populated by mutants, but which at the same time is no longer a truly civil society. Instead, a concealed kind of civil war is going on and certain rules which we hold indispensable for civilised cooperation are suspended. If you are looking at animation technology, then Dark City is also a very special film which in the way it depicts the changing of a city could be seen as the godfather to the latest superhero blockbuster Doctor Strange. The latter represents the current high point of digital 3D animation in which worlds and buildings continuously change. This appears in Dark City for the first time and in Doctor Strange is taken to its extreme.

Seconds by John Frankenheimer, USA 1966

In 1998 Dark City, which is about lost memories, was also seen as pioneering with regards to its treatment of the topic of human identity.

Yes, questions of identity are a very important topic for the genre. In Dark City everyone is a different person each day: every 24 hours you receive a new programme which changes your entire personality. But already in John Frankenheimer’s Seconds (USA) from 1966 a character is reacting to the promise that he can be something entirely different – actually, younger. He is subsequently fitted with another body and that then plays out in a beautifully dark, dystopian way. This topic is also important in the Alien films in the sense that the extraterrestrial life is physically “incorporated” by the attacked astronauts. All these films, whether they are about aliens or technical manipulations, eventually pose the decisive question: what is genuinely human in human beings?

Some popular titles you would definitely expect to appear in this Retrospective are actually absent from your selection. For example, Metropolis. Why?

We have deliberately left out some classics, including Metropolis and 2001: A Space Odyssey, because they have already been thoroughly introduced and analysed in the exhibition “Things to Come”. We found it more appealing to boldly go into less familiar galaxies. So instead of a film by Andrei Tarkovsky, for example, with Pisma myortvogo cheloveka we are screening a less well-known work from his former assistant Konstantin Lopushansky which tells of a post-apocalyptic world no less hauntingly than Tarkovsky himself.

The genre, among other things, feeds off the fact that there are incredibly bad films which, for this very reason, have become tremendously popular. Can some of these “guilty pleasures” also be found in the Retrospective?

To a certain extent, yes. The Fifth Element has fun spending a lot of money to make things look especially beautiful which, in a cheaper film, would come across as totally cringeworthy – just think of the different embodiments of the aliens. Or The War of the Worlds: although the film won an Oscar in 1953 for Best Special Effects, today some parts of it are unintentionally funny, from which it derives its high entertainment value. In this way, the selection also reflects this aspect of the genre.