2024 | Artistic Director's Blog

On Scorsese

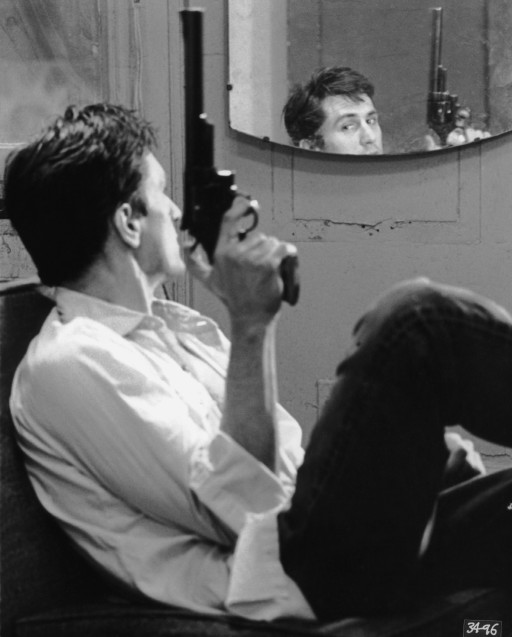

Robert De Niro in Taxi Driver

Carlo Chatrian was Artistic Director of the Berlinale from June 2019 to March 2024. In his texts, he takes a personal approach to the festival, to outstanding filmmakers and the programme.

Each Martin Scorsese film takes us far. The path – which is often at the centre of scenes in his work – evokes a journey the characters embark on with tall leaps, without realising where they are going to end up. It frequently ends in tragedy, because Scorsese has a keen sense of the inevitable frailty of desire and ephemeral nature of the ideals behind actions. His characters appear unfit for the world around them. They live through their time and often profit from it, but they give off the impression of being overcome by things – even when the wheel of destiny is seemingly turning in their favour. This is the feeling I’ve been carrying with me, like an imprinting, after seeing Taxi Driver (1976) – which I think was my first Scorsese film. I spent the entire runtime following that reclusive character attentively, but also with some caution, and right when my affection was consolidating itself, there was the unexpected turn.

The sense of frailty, frequently hidden underneath a tough exterior, is subverted in After Hours (1985). The solitary viewing on the small screen, in the muffled context of one’s own living room, accentuated the Kafkaesque element of the film. Contrary to most of the other characters, Paul Hackett is easy to identify with here. Thrown into a reversed city, like Alice through the looking glass, Paul is someone who, being attracted by the possibility of a movie-like experience, deals with the underbelly of fiction. Rosanna Arquette’s scars, real or imagined, are a metaphor of the violence the bourgeois wish to keep at a distance. But in Scorsese’s vision, violence in human society is inescapable.

Happy reunion: Martin Scorsese and Michael Ballhaus at the Berlinale 2014.

In this film, the images are entrusted to a cinematographer with a very special European background. While far removed from the partnership with Fassbinder, the latter’s influence is impossible to deny in the treatment of surfaces, be they locations or skin. Michael Ballhaus’ contribution consists of anchoring this night-time voyage to bodies and places whose weight is tangible. Besides a sense of fluidity (Ballhaus decided to work in film after visiting the set of Ophüls’ Lola Montès (1955)), the cinematography’s power lies in making the flesh feel like a counterpoint to the dreamlike nature of the storytelling.

The collaboration with the Berlin-born director of photography leads to an extraordinary partnership. Ballhaus’ expressive quest, which puts a new stamp on German Expressionism during this American adventure, reshapes Scorsese’s dramatic vision. As fate would have it, we will be screening the first and the last film of this partnership. From New York to Boston – the geographical distance is reduced, but the films in-between make The Departed (2006) markedly distant from After Hours. One needs only to think of a handful of titles: The Last Temptation of Christ (1988), Goodfellas (1990), The Age of Innocence (1993), Gangs of New York (2002)…

John Heard and Griffin Dunne in After Hours

I can’t remember in which cinema I saw The Departed. But I do have a vivid memory of that opening scene, with the child who looks lost inside a bar/grocery store bathed in warm light. The rest of the film, conversely, strikes my memory as being immersed in a cold colour palette, be it for interiors or exteriors. In addition to its thriller elements, the film also stages a sort of melodrama that is ice cold in light of its context. I think not only of the love affair between the crooked cop (Matt Damon) and the psychologist (a magnificent Vera Farmiga), but also of the relationship between Jack Nicholson and the two male leads. Viewed today, Damon’s character is a lot like the one Leonardo Di Caprio went on to play in Killers of the Flower Moon (2023). An accessory to, and perpetrator of, heinous acts as a form of absurd protection. Both of them are orphans, with a foster father they fear, and for whom they commit the worst acts imaginable. They yearn for a normal life, and at one point even think they’ve made it. Whereas Nicholson’s Frank Costello is very hammy, Robert De Niro’s performance is a more physical one. As always.

Jack Nicholson and Matt Damon in The Departed

While the violence in The Departed is an explicit, pure explosion of rage, Killers of the Flower Moon takes it to another level. Murders are committed as though they were just another task, another favour for a generous employer who presents himself as the uncle-king. The annihilation of the victim goes hand in hand with cynicism, with calculations made out of personal interest. The violent image of America is at its most extreme and desperate. The dusty roads, created by the white man, may be drenched in blood (reminiscent of the opening of Casino (1995), another film about money, where Joe Pesci’s voice-over paints the desert as the place where the bodies are hidden), but the picture opens and closes on an image with the opposite impact. First, an extreme close-up of an eye and the image of a teepee; then, at the end, a colourful dance viewed from above, with the shape of the circle counteracting the straight line. In a film conceived as a Western, where the weak are systematically oppressed, Lily Gladstone’s character resists with her hieratic posture and sweet voice. She’s the starting point of one of the most beautiful and devastating love stories Scorsese has ever brought to the screen. With no happy ending in sight, because blood is still thicker than the heart containing it, but with a capacity for conveying a sense of serenity that floats above the ground. Like a dance from a bygone era.

Carlo Chatrian