2024 | Berlinale Shorts

About Animals, People and Togetherness

Contrasting cinematic forms and subject matters enter into dialogue with one another in the Berlinale Shorts programme. Familiar things are examined more closely, unfamiliar ones approached in an open way, feelings are expressed and doubts permitted. This interview with section head Anna Henckel-Donnersmarck is about visions of communal life, sincerity in storytelling and the role of art in difficult times.

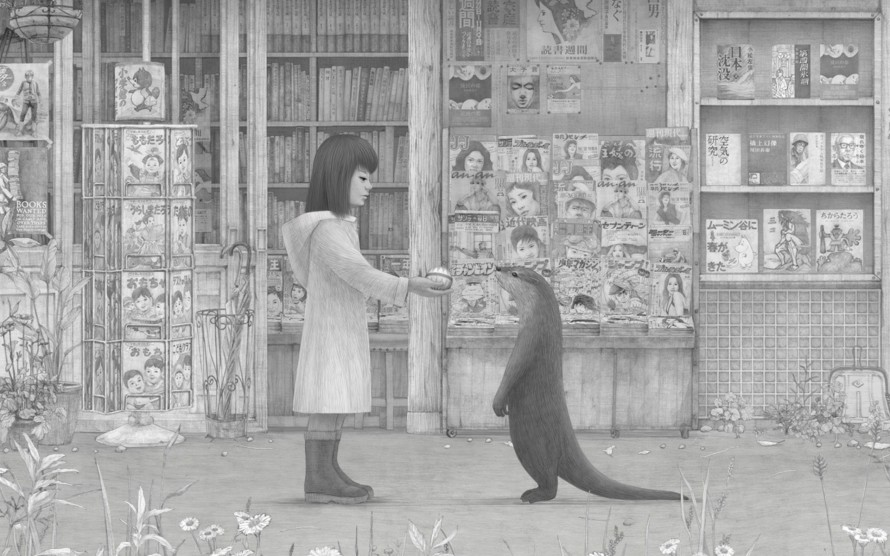

Kawauso by Akihito Izuhara

Which motifs and themes did you encounter when selecting the programme?

The large number of animals is the first thing that catches the eye, whether in the title, the setting or as characters – it’s a trend that can also be observed in feature films. And animals even take on the leading roles in the animated films We Will Not Be the Last of Our Kind, Les animaux vont mieux, Preoperational Model and Kawauso. At first, we were worried there might be too much duplication in the programme, but then we decided to let the animals roam free.

The films featuring animals can be interpreted as a reaction to climate change, to human recklessness and abuse of power. Would you agree?

Yes, absolutely. However, rather than expressing a call to action, the films capture a feeling. Kawauso, for example, turns out to be a deeply sad farewell song to the extinct Japanese otter. It does this by using an idiosyncratic cinematic device: whenever the protagonist wants to talk to the otter, the sound in the film cuts out completely. The two cannot communicate with each other because they do not exist in the same time plane.

Ilias Largo in Oiseau de passage by Victor Dupuis

Short films often employ unusual narrative devices. Do you have any other examples?

In Shi ri fang gu, a camera drone is sent out to search a beach. Quite subtly, the drone takes on a life of its own and carries the entire film off into the realm of the magical. That’s All from Me is a multiply interlaced video letter that, in some passages, dispenses with images entirely. Ungewollte Verwandtschaft (Unwanted Kinship) analyses recorded reports from civilian victims of the war in Ukraine. It opts for the method of re-enactment but at the same time refuses to reproduce images of violence. In Oiseau de passage, a sound recordist uses a highly sensitive microphone to contact his dead friend. Listening together leads to listening to one another and, ultimately, to forgiveness – a gesture that we so rarely get to see and yet so urgently need at the moment.

Meltem Unel and Nursema Çepni in Adieu tortue by Selin Öksüzoğlu

In the press release for your programme, you stated that art can help us to align the compass for our own actions. What did you mean by that?

I think we too often operate in narratives that have long become outdated, are unhelpful or sometimes even dangerous. Art can compensate for this shortcoming by challenging narratives and showing us alternatives. The way we interact with each other is currently so defined by assumptions and mistrust that I find it very touching, for example, when people trust each other on screen, especially when they don’t even know each other.

Are there any films in the programme that express this particularly well?

In Adieu tortue, two very different people meet – a five-year-old girl and an adult woman – and help each other without realising it or even planning to do so. The novelist in That’s All from Me is willing to give advice even though she has never met the person who is seeking it. In the temporary community created on a film set in Shi ri fang gu, moments of solidarity arise between those right at the bottom of the hierarchy. In the drawn animation Circle, passers-by – who otherwise have nothing to do with each other – try to position themselves within a circle in a way that leaves enough room for everyone.

Al sol, lejos del centro by Luciana Merino and Pascal Viveros

This interplay between the individual and a public space or a city is also a recurring motif this year.

Yes, and these cities are located all around the world. Al sol, lejos del centro accompanies two women on a walk through Santiago de Chile. Only at the end do we realise that they have been looking for a place for their love. In Jing guo (Goodbye First Love), two men in a holiday apartment in Frankfurt remember a love that first began in distant Beijing. City of Poets starts by telling the story of a fictional, possibly Persian, city and then becomes a portrait of the first-person narrator’s mother. And Stadtmuseum / Mon Rai is an autobiographical homage to the city of Berlin, to its chaos and its residents.

City of Poets and Stadtmuseum are also portraits of their respective societies. Are there any more of these?

Un movimiento extraño uses dry humour to depict the living conditions in Buenos Aires before the pandemic; The Moon Also Rises describes an atmosphere that could be interpreted to be the one in China during the pandemic; Re tian wu hou captures the feeling of life in an extended family, this time in the China of the late 1990s. For these latter two films, the filmmakers’ own families served as inspiration.

Kaalkapje by Marthe Peters

Drawing from one’s own experiences, and also the specific examination of one’s own biography, often give the films a special intensity. Why is that?

I think it’s to do with the sincerity with which the films are made. And the willingness of the filmmakers to let other people share in their lives, joys and fears, and also their doubts and vulnerability. I’m thinking of Ungewollte Verwandtschaft or Kaalkapje, in which both directors deal with their childhood experiences. The way Kaalkapje talks about the filmmaker’s own cancer and its long-term physical as well as psychological consequences makes this film very unique and touching. That’s All from Me, We Will Not Be the Last of Our Kind and City of Poets are more playful in their first-person narratives and give no indication of where the personal experience ends and the imagination begins. Each film succeeds in developing its own distinctive yet always appropriate formal language to get across what it wants to say. You can feel the sincerity even in the choice of filmmaking devices.

Let’s return to the style of the films. What aesthetics await us in the Berlinale Shorts programme?

We have, for instance, a “machinima” in the programme, which is a film shot in a computer game. As was the case with It Wasn’t the Right Mountain, Mohammad, which we screened in 2020, the director for We Will Not Be the Last of Our Kind built this computer game world herself and entered into a story from the Old Testament as a contemporary avatar. A completely different technique is used in Tako Tsubo: the film is painted in lush watercolours, you can see the wet brushstrokes and the colours running on the paper. And the digital collage in Pacific Vein feels like a contemporary reincarnation of a painting by Hieronymus Bosch.

We Will Not Be the Last of Our Kind by Mili Pecherer

A festival is not just about the films but also about the opportunity for encounters. What do you have lined up in this regard?

Each of the five Berlinale Shorts programmes has six public screenings. It’s best to go to the ones at Colosseum and Titania if you just want to watch the films without interruption. At Cubix and HKW, audiences also have the opportunity to see the film teams who will come on stage for a short conversation after their respective film. And if you’d like to take part in these conversations yourself, you should go to the “Shorts Take Their Time” repeat screenings with audience Q&As in silent green.

You can also meet our wonderful jury at a Berlinale Talents event – there’s more about that on the Berlinale Talents website.

As always, you can find more in-depth information about the films on the Berlinale Shorts blog.

And we’re continuing our Shorts, Communities and Conversations series of talks at the Embassy of Canada where we look at short films outside the context of film festivals. This time, it’s about artistic short films in a journalistic environment.

Ilker Çatak, Xabier Erkizia and Jennifer Reeder

Who is on the Berlinale Shorts International Jury this year?

We’re delighted to have Ilker Çatak, Xabier Erkizia and Jennifer Reeder on the jury. The American filmmaker Jennifer Reeder is a long-time friend of the festival: her film Blood Below the Skin screened in Berlinale Shorts in 2015 while Crystal Lake and Knives and Skin were presented in Generation, and Perpetrator was part of the Panorama programme last year. She’s also a regular mentor at Berlinale Talents and was a member of the Generation 14plus International Jury in 2017. Xabier Erkizia is a sound artist and researcher from Spain. He has worked on over 100 films including El sembrador de estrellas (2022 Berlinale Shorts) and Samsara (2023 Encounters) as well as being a filmmaker himself. Ilker Çatak is a German-Turkish director and screenwriter from Berlin. He has made over a dozen short films and is currently causing quite a stir with his feature film Das Lehrerzimmer (The Teachers’ Lounge). The film premiered in Panorama in 2023, has won numerous awards and is nominated for the 2024 Oscar for Best International Feature Film.

Circle by Joung Yumi

Jury work is teamwork as is filmmaking, and you’re also not alone when selecting the films for Berlinale Shorts. Who was on your selection committee this year?

The Berlinale Shorts committee brings together a very diverse range of expertise, perspectives, experiences and biographies. In alphabetical order, it comprises the Berlinale veteran and festival coordinator Wilhelm Faber; the artist Azin Feizabadi; the filmmaker Alejo Franzetti; the film programmer and producer Qila Gill; the film programmer and student Moritz Maul; the film scholar and curator Maria Morata; and the cultural workers and film programmers Jana Riemann, Sarah Schlüssel and Nihan Sivridag. It’s always a pleasure and an enriching experience to be able to work with this wonderful team.