1995

45th Berlin International Film Festival

February 9 – 20, 1995

“Hollywood has long ceased to be American, instead it has become the international centre for the manufacture of audio-visual products. There are almost as many foreigners as Americans working there. Talent knows no passports or borders. We are Hollywood, too, and if things aren't going well in Hollywood, the crisis will be felt everywhere.”– (Moritz de Hadeln shows claws against the permanent criticism, that the Berlinale is too servile to Hollywood.)

Paul Auster with the Silver Bear for Smoke by Wayne Wang

A triple anniversary year and a city in search for its self

Forty-five years Berlinale, 25 years Forum and 100 years of film were all celebrated in 1995. In hindsight, it appears to have been the fate of the Berlinale that anniversary years were usually seen as luckless. This year too, critics seemed to play into a general atmosphere of crisis – and beyond that failed to notice the actual quality of the festival programme.

Already in the run-up to the festival, problems and obstacles appeared. Due to the massive cuts, the various divisions of the umbrella company Berliner Festspiele GmbH were forced to compete with one another. In the budgetary debates, the Berlinale and the Theatertreffen (Theatre Meeting) were played off one another. The discussion took place amidst fundamental differences in opinion about the new role of Berlin. Here it was about the city’s identity, not just the significance of art and culture and who should pay for it, but also about the fractures in the sworn unity of East and West.

Family affairs

In this already precarious atmosphere, in which anyone could be up next, the internal solidarity between the festival’s various sections and divisions began to falter. The rivalry regarding content between the Forum and the Competition could no longer be swept under the rug. While Moritz de Hadeln publicly depicted the festival in words which were met with disapproval at the Forum, the Forum did little to portray its unique cinematic concept in a relative light and sell it as a part of a harmonious whole. Instead the Forum was a little to self-important in grooming its own image, whose appearance was in fact remarkably independent from the ups and downs of the festival’s image as a whole.

Making matters worse was the fact that the Panorama and Forum were perceived as competitors. Paradigm shifts and new stipulations were by no means surprising, but reflected developments on the international film market. But why weren’t the changes taken as an opportunity to work on a new profile for the festival? The mixture of disunity and silence left an open playing field for external critics.

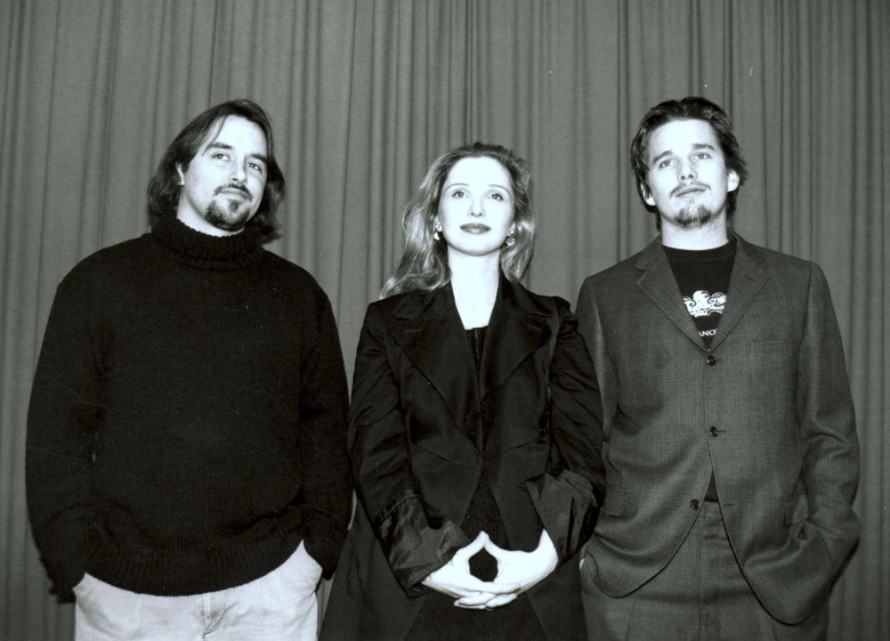

Before Sunrise: Richard Linklater, Julie Delpy, Ethan Hawke

Independents and “small” countries rise to the occasion

In the festival introduction, Moritz de Hadeln asked for “tolerance, patience, openness and above all renunciation of prejudice” when it came to the films. This sounded unusually cautious, while in fact the programme was of quality throughout. Looking back, Bruce Bereford’s Silent Fall, Richard Linklater’s Before Sunrise, Abel Ferrara’s The Addiction and Wayne Wang’s double feature Smoke/Blue in the Face were by no means a bad selection of American films. Complimented by Tom DiCillo’s Living in Oblivion (in Forum) they represented a veritable view into the enormous productivity and diversity of the “Independent” genre.

Robert Benton’s Nobody’s Fool starring Paul Newman and Jessica Tandy and Robert Redford’s Quiz Show, however, didn’t make friends of big American cinema especially happy, because it got about which films the Berlinale didn’t get: Robert Altmann’s Prêt-À-Porter, for example, and Nell by Michael Apted.

But expectations of internationality and diversity were also met by the Competition. In Taebaek Sanmaek | Taebak Mountains, Im Kwon-Taek depicted Korea between colonial rule and the civil war during the 1940s. Mexican director Jorge Fons managed with El callejón de los milagros | Midaq Alley to create an homage to the “small people” of his country. Shmuel Hasfari’s Sh’Chur told the story family history of Moroccan Jews in Israel and with When Night is Falling, a subtly told love story between two women, Patricia Rozema put Canada back on the map regarding film.

Bruno Putzulu, Marie Gillain and Olivier Sitruk in L'appât

There were films from Norway and Spain and several productions by young filmmakers from Hong Kong and China. Margarete von Trotta’s Das Versprechen | The Promise was seen as a successful opening film, Michael Winterbottom’s Butterfly Kiss and Bertrand Tavernier’s coldly realistic L'appât | Fresh Bait offered intense cinema, that dove far beneath the surface, and would have been an honour for any festival. What was lacking at the Berlinale, which other years or other festivals had?

This year Eastern European cinema offered few highlights. Besides Vadim Abdrashitov’s experimental Competition entry Pyesa dlya passazhira | A Play for a Passenger, worth mentioning is also the Polish film Krähen | The Crows by Dorota Kedzierzawska. The story of a young misfit who has to grow up too early, stood out in the Kinderfilmfest.

“Politics and Myth” in the Forum, audience favorites in the Panorama

This year the documentaries dominated the Forum – with a focus on “Politics and Myth” as Ulrich Gregor described in his programme notes. Two controversial film about controversial heroes were Ernesto Che Guevara – The Bolivian Diary by Swiss director Richard Dindo and Ulrike Maria Meinhof by Frenchman Timon Koulmanis. Writing in the “Frankfurter Rundschau”, Sabine Horst accused both films of failed to show the inconstancy of their characters: “While Richard Dindo … at least failed ambitiously, one could say that Koulmanis’ only functions in an uninteresting way,” was her sobering conclusion.

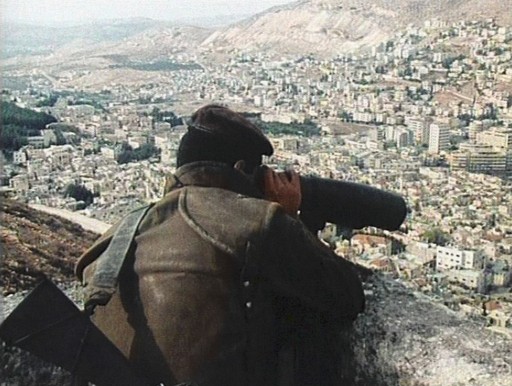

Tsahal

Claude Lanzmann’s five-hour film Tsahal drew similar criticism for not tackling its subject with the necessary depth. The film was a documentary about the Israeli army, in which “not a single image of the six wars in which its was engaged, not even talking about its domestic activities” were shown – as Thomas Rothschild criticised in the “Stuttgarter Zeitung”.

In the Panorama there were two true audience hits with Peter Chelsom’s grumpy but moving comedy Funny Bones and Susanne Oferinger’s Nico-Icon. Films by Antonia Bird, Jean-Luc Godard, Nguyen Huu Phan, Eytan Fox and Idrissa Ouédrogo were proof of the section’s inquisitiveness and open-mindedness. Derek Jarman’s Glitterbug and Marlon T. Riggs’ Black Is...Black Ain't represented passionate political commitment. Both directors had died during the previous year.

Farewells to Manfred Salzgeber and Wolf Donner

It was a year of farewells: founder and organizer of the Panorama Manfred Salzgeber had died the year before. His strength had been his openness: for all things new, for the viewpoints of others, open-minded advocacy for that which was important to him, open treatment also of AIDS, the illness which ended his life prematurely. “How often did we profit from his always clever suggestions – even the most radically passionate ones,” wrote Moritz de Hadeln in the festival introduction. Still today, the Berlinale bears the sign of this intellectual passion. In honour of Salzgeber, the festival showed his favourite film: Chaplin’s Monsieur Verdoux.

Wolf Donner, who had directed the Berlinale from 1977-1979 for three years and put the festival on a new course, had also died the year before. In his honour Deutschland im Herbst | Germany in Autumn was shown again, in order to remember Donner’s passion for contradiction and critical viewpoints, and the courage with which he rightly stood behind sometimes unpopular decisions as a festival director.