1974

24th Berlin International Film Festival

June 21 – July 2, 1974

"The contracting parties shall encourage cooperation in the field of film. For this purpose, the organization of film shows and premieres, the exchange of feature, documentary and newsreel films, co-production of feature and documentary films, as well as a reciprocated participation in international film festivals shall be promoted." – Article 7 of the German-Soviet Cultural Agreement.

Cold War: Berlinale posters along the East-West border in 1954.

The ice is broken

1974 was a milestone in the history of the Berlinale: For the first time, a Soviet film was screened in the official programme of the festival. The title of Rodion Nakhapetov’s debut film, S toboy i bez tebya – With You and Without You, read like a retrospective commentary on the decades-long tug-of-war that had preceded this event. “The story of the socialist states’ absence from the Berlinale”, Wolfgang Jacobsen writes in "50 Years of Berlinale", “is a highly instructive tale of politics and culture; it is a substantial chapter in the history of East-West tension; a Cold War tragicomedy, a drama with shifting roles and changing protagonists.”

Stages of separation

The advisory board had already decided at the founding of the Berlin Film Festival not to invite any films from “Eastern bloc states”. Officially, this stance hardly changed until the end of the 60s. Unofficially, however, there were serious attempts at rapprochement. At times these were aimed at the DEFA, the state film company of the GDR; at times contact was sought with “Sovexport”, the body responsible for representing Soviet films abroad.

Meanwhile, the other side also had trouble expressing official interest in an event that primarily served the “imperialist ambitions of the United States”. The changing roles referred to by Jacobsen were variously filled by the Berlin Senate, the Foreign Ministry, the festival itself, or individuals with good connections. On the other side it was the Politburo, the ambassador, or Soviet film functionaries. In some years, Easter European films seemed like they were only a formality away from taking part in the Berlinale, but by the following year everything would look completely different. The diplomatic conditions were constantly changing and difficult to calculate for the festival.

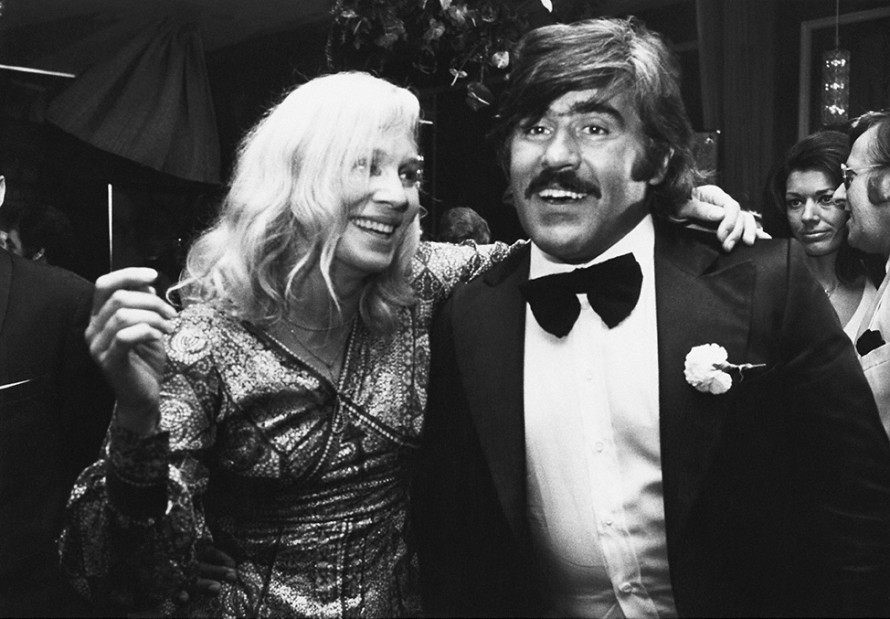

Ingrid Thulin, Mario Adorf

Only occasionally would an Eastern European film show up at the film market, or a Czechoslovakian or Russian observer delegation would register for the Berlinale. Thaws did not last long during the Cold War and attempts at understanding and tolerance did not grow beyond delicate shoots. The most significant obstacle to a participation of the socialist states in the Berlinale, evoked again and again by both sides, was the “special diplomatic status of Berlin”. This status was charged with a symbolism that for a long time could be overcome neither by reason nor by political pragmatism. Besides the difficult political reality, the “diplomatic status” included all sorts of peculiarities. For instance, West Berlin did not appear on East German maps, and for a long time the official stance of West Germany was that the GDR did not exist either.

Freedom and necessity?

The decision as to whether the socialist states should take part in the Berlinale was based not on artistic but on (geo-) political factors. Alfred Bauer’s work here resembled that of a diplomat more than of an artistic director, and the interests of the festival were seldom identical with those of international politics. By the time Eastern European films started being shown at Cannes and the Karlovy Vary Festival was granted A-status, Berlin’s special role came to be seen as an obvious shortcoming. Great cinematic art was being created in the socialist states, but it could not be shown in the city whose destiny it could have been to bridge the gap between East and West.

Not until Willy Brandt’s policies led to a gradual détente in East-West relations in the early 1970s, did the climate begin to change for the Berlinale. As soon as the treaties with the Eastern bloc were signed in 1972, Alfred Bauer began to harbour hopes about the Soviet Union taking part in the festival. There was a promising meeting with Soviet Ambassador Abrassimov in Cannes, and Bauer’s efforts with Hungarian representatives also gave grounds for hope. In the end, however, the Berlin Senate argued that there was not enough time to sufficiently prepare for such a groundbreaking move.

Bauer shifted his hopes to the coming year and held numerous talks with Czechoslovakian, Polish, Bulgarian and East German representatives on the occasion of the Karlovy Vary Festival in August 1972. There was briefly talk of a compromise, in which a selection of DEFA films would be shown as part of the Berlinale programme, but this too was unsuccessful. The Soviets repeatedly turned down invitations from the Berlinale without comment; not until June 1973 did a letter to Bauer from the Soviet consul provide a belated explanation: The invitations had been issued “with the agreement of the government of the Federal Republic of Germany and the Berlin Senate”, thus using the official language of the – meanwhile obsolete – Four Power Agreement. The Soviets saw this as blackmail, and made their participation dependent upon a reduction of West German state influence on the festival.

Not only did the Federal government’s sponsorship of the festival cause offence, but also the Federal Film Prize Award, which always took place during the Berlinale and in Berlin, as well as the traditional reception by the West German president. Soviet Consul General Sharkov and his Vice Consul Nikotin met three more times with Senate leader Herz and government official Schröder. But even without significant changes in the festival’s structure, on June 3, 1974 – two weeks before the beginning of the festival – Alfred Bauer received a call from Nikotin, who told him that the Soviet Union would take part in the Berlinale with a film “out of competition” and an observer delegation. The ice was broken.

Arthur Knight, Margaret Hunxman, Pietro Bianchi, Gérard Ducaux-Rupp - Four of the nine members of the International Jury 1974

A year of optimism

In addition to the universal joy over this event, there was a generally positive impression left by the 1974 Berlinale. The reviewers especially emphasized the significant improvement in the Competition films. Masterworks like Fassbinder’s Effi Briest and Tavernier’s L’Horloger de Saint Paul | The Watchmaker of St. Paul made the hearts of audience and critics alike beat faster – the fact that Fassbinder’s film went away empty-handed in the awards ceremony was met with equally unanimous incredulity and led to harsh criticism of the jury.

There was praise however for the ways in which the Competition and Forum programmes had come closer together and for the interesting cross-pollination that ensued. Exemplary for this were two films by the Persian Sohrab Shahid Saless. His debut film Yek Etefagh sadeh | A Simple Event screened in the Forum while Tabiate Bijan | Still Life was shown in the Competition. Films like these – sparse, realistic stories of daily life – led Peter W. Jansen to write in the "Frankfurter Rundschau" of a “festival forming an almost integrated whole”. He especially praised the marked increase in artistically ambitious films in the Competition: “In the guise of historical dramas, comedies or parables, these films address, more or less directly, perfectly concrete things – primarily the conditions in which the individual has to live in his particular social reality.”