1966

16th Berlin International Film Festival

June 24 – July 5, 1966

“Autograph books no longer exist. Actors, although they are probably more intelligent than they once gave on, no longer have to be able to write their name. No one demands it of them publicly.” – Film critic Friedrich Luft in "Die Welt"

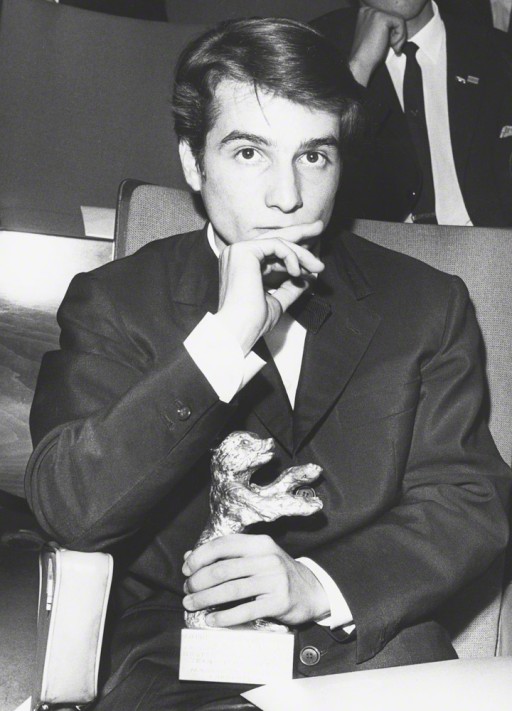

Jean-Pierre Léaud with a Silver Bear for his acting in Masculin, Féminin

A new generation takes over

The “new generation” is present at the Berlinale and shows what it’s capable of: films by Satyajit Ray, Jean-Luc Godard, Carlos Saura and Roman Polanski are shown and a new love of debate is noticeable among the audience. Moving themes have reached the Berlinale screen and observers mark a definitive change in the festival: the audience is younger, hair is longer, the fuss around stars subsides and the themes become more serious. The medium has freed itself from the constraints of entertainment and has evolved into a medium of debate.

The era of the podium discussion begins. One is asking “What is the future of film?” and Peter Schamoni, Roman Polanski, Pier-Paolo Pasolini, Satyajit Ray, Jean-Paul Rappeneau and Volker Schlöndorff appear on stage to try to come up with an answer. But the future has only just begun and nobody feels like they are ready to make a reliable prediction. Instead, they focus on the present and the real-life conditions under which films are produced, and the aesthetic and societal challenge of television. The “competing medium” had become well established – the German Film and Television Academy in Berlin and School for Television and Film in Munich had opened their doors shortly before. You could now study filmmaking.

Schonzeit für Füchse by Peter Schamoni

Arguing means choosing sides

Even before the festival began, there was fierce public debate. Ulrich Gregor had moved from the selection committee to the advisory board of the Berlinale and there was disagreement about his successor. The federal ministry appointed the critic Dieter Strunz of the “Berliner Morgenpost”. But amidst the critics there were camps – one spoke about “schools” – and Enno Patalas, a supporter of Gregor, protested against Strunz’s appointment. In several articles in the magazine “Filmkritik”, he attacked his colleague in unusually harsh tones, but also raised fundamental questions about the identity and structure of the Berlinale, which would be discussed for years to come. He demanded that the Berlinale emancipate itself from its “role models” Cannes and Venice. The Berlinale should focus on its strengths and become a festival of “another style”.

Combatively presented, Patalas’ criticism first encountered a headwind. Looking back, his suggestions were clairvoyant. Here someone was truly speaking of the future: The Berlinale should be defined as a “ festival for the audience rather than for the stimulation of consumers…, a festival of the auteur rather than the star, a festival of discussion rather than representation, a place of confrontation, not simply mutual compliments, an exhibition of new films, rather than a parade of the tried and tested.” The fronts were marked.