2012 | Special Presentations

Happy Birthday, Studio Babelsberg

Studio Babelsberg: The setting "Berliner Straße"

In their 100-year history, the Babelsberg studios went through five different political systems, during which a huge number of different films were produced. How did you narrow down the selection for this special Berlinale series?

The special series is, one could say, a birthday present for Studio Babelsberg. We have selected ten films that were important for specific phases of the development of Babelsberg. Of course such a selection can never truly represent the studio’s 100-year history.

The founding story

How did cameraman Guido Seeber end up moving from Berlin to Babelsberg in 1911?

The Berlin studio of Deutsche Bioscop had become too small. Seeber was the technical director. On his search for a new location, he found an area in what is today Babelsberg, which was, in many respects, ideal. There, the company built a new, and, for the first time, a ground-level studio. Until that point, studios were in the attic, because at the time a lot of light was required to work with the still low-sensitivity film material. The film pioneer Guido Seeber conceived this studio and shot the first films there. The shooting of Der Totentanz with Asta Nielsen began on February 12, 1912.

A whole series of films with Asta Nielsen were directed by her husband Urban Gad. How significant were stars such as her for the founding era of the studio?

Asta Nielsen was an anomaly because she had a very modern understanding of how to act especially for film. Compared to many other big stars of the time, who still fostered a highly theatrical style, she came across as very natural. That was already noted by many critics of the time and Asta Nielsen could be called one of the first big European film stars. The worldwide success of such films ensured the studio financial security during this early phase.

Marlene Dietrich in Der blaue Engel, D: Josef von Sternberg, DEU 1930

The First World War broke out just two years after the foundation of the studio. What impact did the war have? What changes occurred?

The war resulted in special production conditions for German film as a whole. Most of the foreign competition – especially the big French companies – was barred from the German market during the war, and domestic companies prospered. During this time, a German cinema, cut off from international developments, could establish itself, and act more independently.

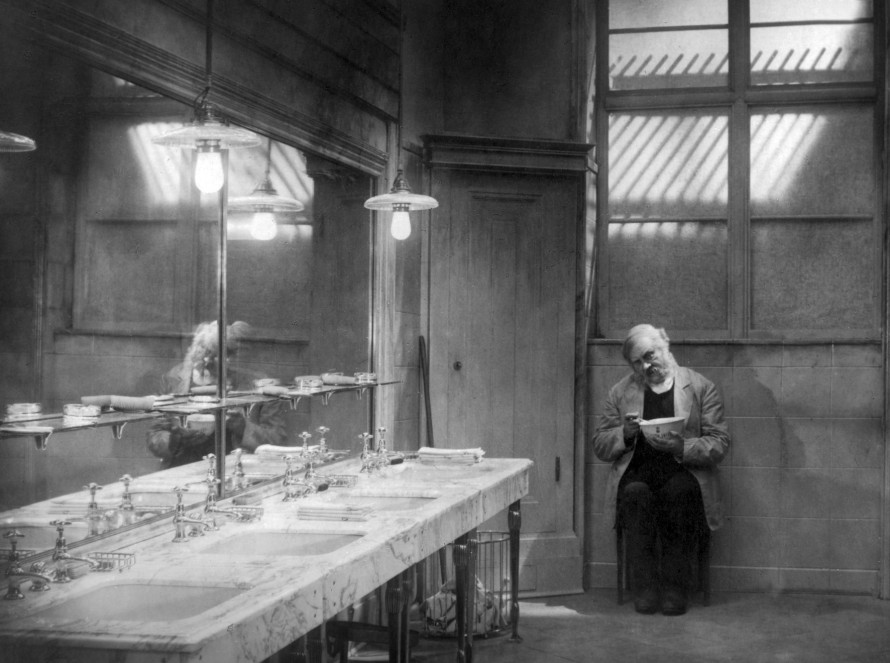

Emil Jannings in The Last Laugh, D: Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau, DEU 1924

The heyday of the 1920s and 1930s

During the 1920s, the studio developed into the most energetic and innovative in Germany. The “Myth of Babelsberg” was encapsulated by films such as Fritz Lang’s Metropolis and Josef von Sternberg’s Der blaue Engel. What were the innovations of the time?

The founding of Ufa and its acquisition of the Babelsberg facility marks the beginning of a new period of German film history. For the first time, a financially strong film corporation was involved. In the 1920s, Ufa produced a certain mixture of films. It produced a lot of low-budget movies, invested in so-called “mid-range films” and had – this was unique – the ambition of achieving international success with grandiose productions.

To do so, a specific combination of talents came together in Babelsberg: creative cameramen such as Karl Freund, architects like Otto Hunte and Erich Kettelhut, directors like Fritz Lang, Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau and Ernst Lubitsch. They produced big-budget films with stars such as Pola Negri, Henni Porten, Emil Jannings, Conradt Veidt, who were also suited for the international market. In particular the nuanced cinematography and free-moving camera, as found in Murnau’s Der letzte Mann (The Last Laugh), formed the studio’s signature style.

Studio Babelsberg during the Nazi period

In 1928, the publisher Alfred Hugenberg bought the studios. From 1933 all Jewish members of staff were fired. How would you describe the upheaval of that time?

One has to distinguish between the takeover by Hugenberg, a German nationalist publisher and the Nazis’ rise to power in 1933. Under Hugenberg, Ufa continued to produce entertainment films. For the most part the company remained loyal to its directors and writers. What was new was that Ufa produced more so-called “national” works, stories that appealed to conservative segments of society.

But then, in the early 1930s, Ufa developed a genre that was a reaction to what was happening in society with a lightness, which is unique in Germany: talkie operettas, in which most of the directors, screenwriters and composers were Jewish. It was a very short-lived genre that was immediately eliminated by the Nazis. Following Goebbels’ famous Kaiserhof speech, many Jewish employees, including most of the protagonists of the talkie operetta genre, were fired.

What sorts of films were produced under the Nazis?

The National Socialists first wanted to prohibit the production of films that contradicted their ideology. Goebbels understood the value of Ufa’s entertainment films very well, and they continued to be produced and weren’t hindered. As a kind of replacement for the talkie operetta came the 1930s revue film, with new stars such as Marika Rökk. Many melodramas were produced, with Zarah Leander in particular. Otherwise, there were of course the propaganda films, whose share of the total production was determined politically.

Hans Albers in Münchhausen, D: Josef von Báky, DEU 1943

Which films from this period were selected for the Babelsberg series?

Ufa celebrated its 25th anniversary with a bombastic production, Münchhausen, with lots of stars including Hans Albers, based on a script by Erich Kästner, who was credited under a pseudonym because of the writing ban placed on the author. This film, a prestige production shot in Agfa colour, on the one hand seems separate from that period of history, yet hints at it with many references and nonetheless was shown as the official anniversary film. It would have been hard to leave it out of the selection.

DEFA

After the war, the allied powers set up their news center for the Potsdam Conference in Babelsberg. The first film produced after the war was Die Mörder sind unter uns (The Murderers Are Among Us) by Wolfgang Staudte. Under what sort of conditions was this film produced?

Die Mörder sind unter uns is the first feature by DEFA, the newly founded East German film company, which would later take over the Babelsberg studio facility. This film is set in the rubble of Berlin. It mirrors the state of the country and tries to reflect the guilt that many Germans were burdened with. It was a new beginning, but that’s not the only reason it was so important.

By the fall of the Berlin Wall, more than 1,500 films had been made. What was unique about the DEFA studio system?

First of all, it was a classic studio system, but operating under new conditions, with full-time employees and projects that allowed long-term preparation, but also subject to the guidelines of the communist party (SED). DEFA produced a very wide variety of films. For example, it developed “Indian films” with Gojko Mitić – an answer to the West German Karl May films. In the 1950s and 1960s they also produced crime stories and in general a lot of entertainment films.

DEFA movies are distinguished by their high professional standard and outstanding craftsmanship. Typically for studio systems, there is a certain rejection of experimentation and the avant-garde. Still, directors such as Egon Günther, Frank Beyer and Konrad Wolf (Goya) were able to make artistically independent films.

Ilse Voigt and Angelika Waller in Das Kaninchen bin ich, D: Kurt Maetzig, DDR 1965

Again and again, films were subject to censorship or banned from theatres. Nearly the entire production of the years 1965/66 – the so-called “Kaninchenfilms” named after the film Das Kaninchen bin ich – were banned at the 11th conference of the Central Committee of the SED. What sorts of limitations were DEFA filmmakers up against?

This ban encompassing nearly the entire annual production of the studio sent a clear signal that films addressing contemporary issues and problems in East German society were not desired by the SED at that time. This meant that some directors had to work in TV or they tried to find subject matter that wasn’t obviously relevant to the time. Others left for the West. This hampered DEFA’s capacity to produce films. The movies no longer reflected the reality of society.

In 1990 several of these banned films were shown for the first time at the Berlinale. What significance did the Berlinale have for the studio?

For a long time no films from Warsaw Pact countries were shown at the Berlinale. The first Soviet film was screened at the Berlinale in 1974. In 1975 the first DEFA film, Frank Beyer’s Jakob der Lügner (Jacob the Liar), was the first DEFA movie in the Berlinale Competition. From then on, the Berlinale acted as a showcase for DEFA and several films ran successfully in West German cinemas after premiering at the film festival – such as Konrad Wolf’s Solo Sunny.

Adrien Brody in The Pianist, D: Roman Polanski, FRA/POL/DEU/GBR 2002

Present and future

After the fall of the Wall, the studios were privatized. There were a lot of ups and downs in the beginning. The current production of Cloud Atlas starring Tom Hanks and Halle Berry is the most expensive film ever produced in Babelsberg. What happened in the years between?

For the Studio Babelsberg and for all of Germany as a location for film production in general, the German Film Fund surely plays a decisive role. Studio Babelsberg has used this funding very wisely by bundling the available resources with international productions. Things have been getting very well for a number of years now, boosting the studio’s international reputation. Directors from the US, but also other countries, are happy to produce their projects there because they know that Babelsberg works with a high degree of professionalism and that there is a large pool of creative, flexible staff.

How would you compare Babelsberg to Hollywood?

Hollywood emerged in the teens of the previous century because the city magistrate could advertise the location with 350 days of sun per year. As a result the most important film industry in the world developed there, with production, distribution and screening all intermeshed. In Babelsberg we once again have a wonderful production location suited to large international projects, in which the Studio Babelsberg is involved as co-producer. That successful formula attracts the likes of Quentin Tarantino and Sha Ruk Khan.

What can we look forward to over the next 100 years?

Today Studio Babelberg is advantageously consolidated. Which means we can at least look forward to more big productions being made there in the coming years. And that’s great news.