2009 | Perspektive Deutsches Kino

Boom of the Family and Individual Life Paths

Once again Perspektive Deutsches Kino shows that German film has a productive younger generation. This is displayed not only by the range of well-known actors and already successful young filmmakers in the programme, but also by this year’s debut entries. We talked with section head Alfred Holighaus about the 2009 programme, in which family relations, inexplicable behaviour and different forms of maturity play a central role.

Clemens Schick and Carlo Ljubek in Stefan Schaller's To Each his Own

How would you describe this year’s selection process? Was there a surplus of good movies or was if more like looking for a needle in a haystack?

With around 300 valid submissions, there were more registrations than ever before. That means that, if you look at the few programme slots in the Perspektive Deutsches Kino, we of course experienced a large oversupply. Nevertheless, putting together a satisfactory programme was, at the end of the day, not so easy. Especially when it came to full-length features, we observed a shortage of convincing submissions. It is striking that at the end we have only one feature film longer than 90 minutes in the programme. Others are half as long. Or an hour. Or barely 80 minutes. In any case, this year we have the programme with the shortest long films.

What is the situation with the film academies? Admissibly, small fluctuations are normal, but when a third of the Perspektive films come from Ludwigsburg, it looks like more than just a coincidence.

It does stick out. But it’s more of an indirect coincidence. Our programme has no quotas. We watch the films and select them based on their quality. And especially the films that we have from Ludwigsburg this year came to us at different times and over various channels. You don’t just drive to Ludwigsburg, watch all the films and then choose three films for the programme at the end of the day. Long-term processes and connections often play a role.

Stefan Schaller, for example, attracted my attention with a film last year, but it had been completed at the wrong moment in time. When he presented Jedem das Seine (To Each his Own), which even went beyond my expectations, it became clear to me that it had to run in this year’s programme. In this way things often develop bit by bit, as opposed to playing film academies off of one another. It is always about the particular film. The final statistical result is – seen purely mathematically – coincidental. But perhaps this school is in a good state right now.

As every year, there are also several films that were made in cooperation with television. Are the television institutions sufficiently engaged and do they support young, imaginative filmmakers? Or are they sometimes too risk-averse?

I don’t think they are too risk-averse. One has to watch out a bit that at the end one doesn’t spawn too many young filmmakers (laughs). No, they do it very well, though it only takes place on two levels: The flagship is surely “Das kleine Fernsehspiel” on ZDF, which places no restrictions upon its support of young directors, whether it is the content, the form or time. For them, it’s really about the material that they want to develop and produce with the filmmakers. Of course a lot of film students who are making their first feature end up here. Often enough proper cinema formats originate out of this work.

A further possibility is offered by “Debüt im Dritten” at the various ARD channels, at which you can observe the same phenomenon, just somewhat less precisely formatted. The fact that the private channels don’t have an engagement in this field lies, I believe, in the nature of the thing: they don’t have a cultural obligation. And you can only support young talent if you have a cultural obligation.

Max Bauer and André Hennicke in Polar

“It seems you somehow need the small…”

Family matters always come up in your programme again and again. This time in two films sons tackle their double-edged relationship to their fathers: Martin Busker’s Höllenritt and Polar by Michael Koch. Does something like the collapse of the nuclear family and adjustment to the parents’ new partners lie behind this?

Interestingly, the theme is really booming this year, even if it has, as you say, always played an important role at the Perspektive. It can be explained by the general, worldwide tendency that family is again considered valuable. It’s becoming a refuge, a defence against the societal and economic consequences of globalisation. At this year’s festival the topic seems to be omnipresent. You see it even more in the Competition films than in the Perspektive. Again and again and in all sections, it’s about broken relationships, and the relationship of the children to their parents and vice versa. It seems you somehow need the small, because the big is getting bigger all the time. That’s how I would explain it.

You say a recurring theme of the Perspektive Deutsches Kino 2009 is the edge of the abyss. But isn’t it more about the search for a place in society? Not necessarily in the sense of normality, but still with a connection to the social consensus? Is there still something outside of society?

I consciously said edge and not outside. “Abyss” sounds more exciting, it’s not for nothing that we have the cliff-hanger as an important dramatic tool. In the film there are actually people and characters who assume and represent totally individual positions, which is why they exist on the edge in the perception of the public. Interestingly all of the three long documentaries deal with people who don’t conform to certain societal norms, and so they take their own path. Peter Dörfler’s Achterbahn (Catapult) is about a man who follows his own very personal vision of life, but creates a huge mess when he brings his own son to prison in South America.

Does the family resurface?

That runs through a lot of films. The protagonist in Claudia Lehmann’s film Hans im Glück (Berlin Playground), Hans Narva, simply never went along with the crowd, but always followed his own path. He also has a son whom he meets once in a while. At any rate Hans Narva has an incredibly original worldview, with which he is constantly deceiving himself, but which regularly causes joy in others. The things are often double-edged.

And in Wir sind schon mittendrin (Generation Undecided) by Elmar Szücs one asks oneself: when are the main characters going to finally grow up, for God’s sake. And yet they’ve already obtained a form of maturity, but one which doesn’t fit the social norm. And so the film raises the question of the “right” definition of maturity. The maturity which is addressed in all three documentaries has nothing to do with conforming to society and going along with everything. It consists of the development and asserting one’s own path in life.

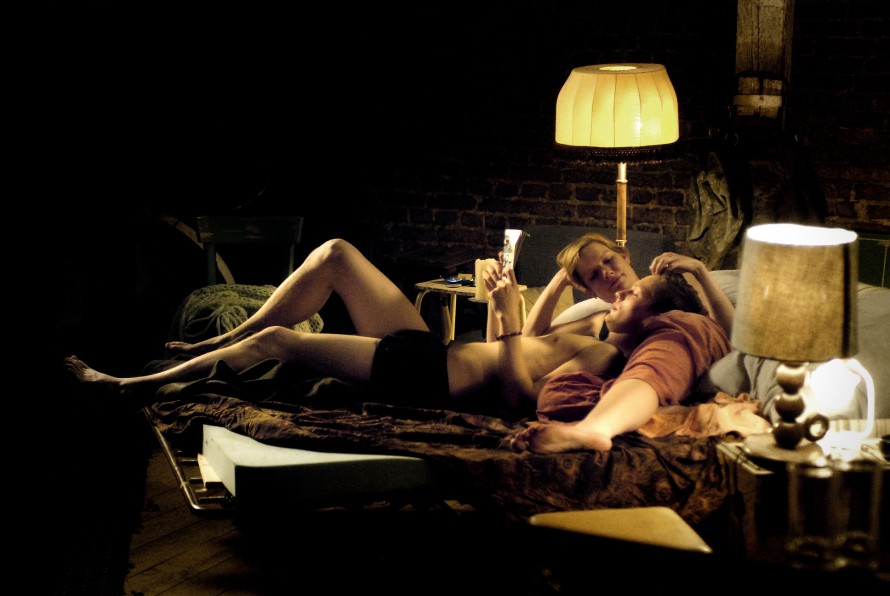

Gitti

Confidently filling the form

Do the films in this year’s Perspektive consciously break rules on a formal level or do they try to fill existing forms?

I would say that they approach existing forms and rules well and with confidence. This year is not a big exhibition of new forms and dramatic techniques. This time we don’t have anything as refined as last year’s Drifter, for example, which had its extraordinary dramaturgy and workmanship. The documentaries are all – as one says in fiction – “character-driven”. They trace their protagonists and that results in the form. No formal experiments.

Is that also true for Gitti?

It’s actually most true for that film. The movie’s high quality is reached, primarily, by the extreme opening up of its main character. Sure, Hans Narva also displays his entire life, but he – as a musician and performing artist – is also used to it to a certain degree. Gitti has no practice and exposes a lot about herself during her search for a man as a pensioner – and does so in her own home. To bring someone so far, that has a different quality and demands a lot from the filmmaker.

Distanz (Distance) by Thomas Sieben sounds like a very unusual film, which can’t be described abstractly. When I read about a schizoid character and the loss of control, I was first reminded of The White Sound. Does the association make sense?

I deliberately formulated it abstractly. But an association to Der freie Wille (The Free Will) would fit better. The film is very different to The White Noise in which basically cinematic images are found for a portrayal of an illness. In Distance it’s not an illness being described, at less not in the foreground. It’s a tale of a puzzling character which very strong in the cinema and which one has to endure. Nothing is explained to the viewer and that’s the source of its quality. At no point are you told that it’s a schizoid guy and there’s never an explanation of why he is that way. But the film shows that that exists. Besides, it’s very well told in stringent, calm visual language and is incredibly exciting.

Sandra Hüller with Jacob Matschenz in Fly

Growing perspectives

In the case of Lars Jessen, who is bringing his literary adaptation Dorfpunks this year, you have invited a director who won the Max Ophüls Award in 2005, and whose film already has a national and international distributor. How does a relatively established filmmaker like him fit into the Perspektive’s pattern of predation?

It is in fact Jessen’s second cinema film. He made some TV in the meantime, a very good episode of Tatort, for example. Besides, Dorfpunks really has a lot to do with the Perspektive in terms of production conditions, form and content. Actually we practically never invite a director twice, but it’s also good to show that these people develop further. That’s the case twice this year. Claudia Lehmann, the director of Hans im Glück, had a short film she made in film school in our section two years ago. Her current film was produced independently after her studies. Totally different form, completely different content and absolutely different working conditions.

Sandra Hüller, Franziska Petri, André M. Hennicke are just three of the well-known actors who took part in the smaller productions of this year’s Perspektive. Is this sort of commitment to young filmmakers considered the right thing to do these days? Are these films very much tailored for these actors?

I’m really happy you asked that question, because I always asked myself, how I could bring up the fact that we had all these great people. No, it’s really noticeable, but not totally inconsequential, because over the past seven years we always had actors of that calibre and greatness in our audience. It’s great to have them on the screen now.

I’m really happy to be able to welcome these people in our programme. And this year, thankfully, there are more of these well-known names who are interested in and committed to young talent. In the case of Distance, Ken Duken is even the producer of the film. Which is a trend you see more and more. If you, as a German actor, become a producer, you can’t make a huge film right away. Most are low budget or newcomer productions – as is the case here.

“Tailored for them” applies to the case of Distance only insofar that Ken himself absolutely wanted to play the role himself. With Franziska Petri and Sandra Hüller I believe that there was already a vision. But finally one has to ask the director himself, which you should do with us in the cinema.