2024 | Retrospective

Busting the Canon

Section head Rainer Rother and Annika Haupts, member of the selection committee and programme coordinator, on the high percentage of female directors in the 2024 Retrospective "An Alternate Cinema – From the Deutsche Kinemathek Archives" and why the films are particularly worthwhile for a young audience.

Volker Spengler, Brigitte Kausch and Dietrich Kuhlbrodt in Das deutsche Kettensägenmassaker (The German Chainsaw Massacre) by Christoph Schlingensief

The 2023 Retrospective encompassed some 30 films from five continents. How does this year’s selection differ from that and other previous Retrospectives?

RR: The key difference is that this time, we concentrated on films from the holdings of the Deutsche Kinemathek – and exclusively on German movies. The decision for this unusual Retrospective arose from the special situation of this year’s Berlinale, with its reduced budget, and also because of the venues available, which meant that only our newer digitised films can be shown. They are all available for distribution with English subtitles.

How did that decision affect the content of the programme?

RR: Our collection includes one very well represented area that one might not automatically associate within a cinematheque, namely independent, experimental, and underground films. We think those are particularly interesting, especially for younger audiences. So we decided on the theme “Alternate Cinema”.

AH: Added to that was the fact that we celebrated the Kinemathek’s 60th anniversary in 2023. So we took a fresh look at our holdings and wondered, which films go beyond the canon? How can we present them in a new way? How can we bring together those very different films and contrast them with each other? This re-examination opened up a new perspective that came into effect in the Retrospective.

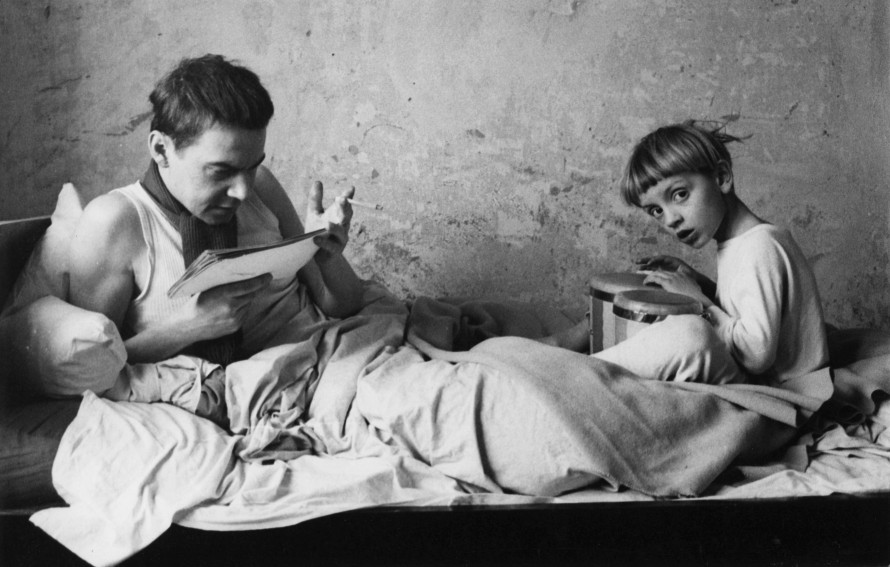

Tobby Fichelscher and Danny Fichelscher in Tobby by Hansjürgen Pohland

“Das andere Kino” or “Alternate Cinema” is a term used as a battle cry by Hamburg’s filmmakers cooperative in the second half of the 1960s. To what extent can the Retrospective films made before the 1960s be categorised that way?

RR: We looked for films that were made outside the mainstream. We see “An Alternate Cinema” as a conceptual umbrella, a way to bring those films under one roof. To ensure a certain thematic continuity, we decided to not include earlier films – from the Weimar Republic and the 1950s. Our selection starts in the early 1960s, with Tobby (1961), Zwei unter Millionen (Two Among Millions, 1961), and Die endlose Nacht (The Endless Night, 1963). Those are films that were in fact considered “alternate” within the context of the cinema at the time. In Tobby, it might have been the authenticity, because it was shot entirely on location. In Zwei unter Millionen the love story unfolds differently than in a classic melodrama, and Die endlose Nacht has a touch of the experimental about it, because it focuses on a single night and a single setting.

Anna Levine in Im Land meiner Eltern (In the Country of My Parents) by Jeanine Meerapfel

AH: There is also a leitmotif that runs through all selected films, which could probably be best described as “societal non-conformity”. They are films that are very closely and realistically tied to real lives. The films do not work through whatever the contemporaneous situation is, they work within it. They mix documentary forms with narrative elements, which give these films a particular abundance of tension. Another factor is the critical relationship to contemporary German history. The reflections of the past range from the continued discrimination against Black travellers in The Endless Night to Thomas Brasch’s film Engel aus Eisen (Angels of Iron, 1980), set in the post-war era and centred on a former Nazi executioner, to Jeanine Meerapfel’s autobiographical movie Im Land meiner Eltern (In the Country of My Parents, 1981). Ulrich Schamoni addresses German history playfully, including Nazi memorabilia in Chapeau Claque (1974).

Are there fixed criteria for attributing a film to “alternate cinema”?

RR: I think those criteria change depending on the decade. In the 1960s, realistic sound and images were key. And conditions in society were not just accepted, but questioned. In the 1970s and 1980s, new forms developed which were perceived as awkward. So there is not one criterion, or even two or three – it depends on the context of the era whether a film can be classified as “alternate cinema”.

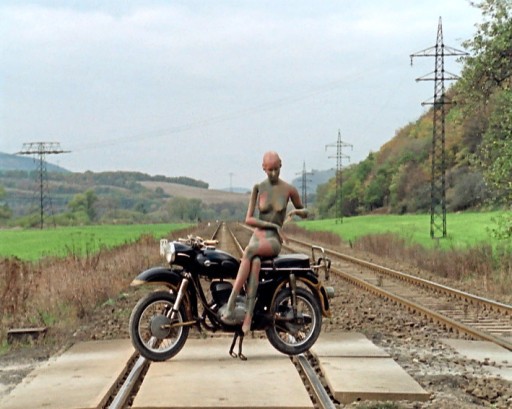

Dark Spring by Ingemo Engström

AH: But it was important to choose films that considered society at the time they were made – that they reflected on their own here and now. For instance, Shirins Hochzeit (Shirin’s Wedding, 1975) gives us the perspective of a Turkish “guest worker” in Germany, while in Fegefeuer (Purgatory, 1971), Haro Senft uses new aesthetic forms to examine left-wing radicalism and terrorism. The selection also includes films that reflect on filmmaking itself, such as Germany’s subsidy system in Der kleine Godard (Little Godard, 1978), directed by Hellmuth Costard, or Ingemo Engström’s Dark Spring (1970), which asks the question “how do women make films?”.

The real locations and documentary elements are often reminiscent of France’s Nouvelle Vague. Is “alternate cinema” actually “poor man’s cinema” that makes a virtue of necessity?

RR: “Poor man’s cinema” in the sense of Arte Povera mainly consisted of female filmmakers, who were largely shut out of the film industry. They had to find ways to get their films financed. It is no accident that our selection includes – statistically speaking – a relatively high percentage of films by women directors. The French model of the New Wave certainly played a big role. But the trends in Poland or Czechoslovakia are just as important. Playful forms were developed that were implemented by people who said to themselves, ‘I don’t want to make the films everybody else has already made. I want to make films that tell my story, the story of my world, my experiences’. And the various “new waves” play a big role in that.

Leuchtkraft der Ziege – Eine Naturerscheinung (The Goat’s Intensity) by Jochen Krausser

Does the selection include a regional focus? Were there places that were central to an “alternate cinema” in Germany?

RR: The selection was made exclusively from our collection. Since the Kinemathek was funded by Berlin for decades, it focused strongly on Berlin issues. But at this point, there is also a strong presence of films from the Hamburg scene, including Roland Klick’s Supermarkt (Supermarket, 1974). However, for this case and for archival holdings from other regions, we have not by any means digitised all films. But our selection represents a good regional cross-section. It also includes productions shot in Munich, which were often more narrative than those in Berlin or Hamburg.

AH: And there are some unexpected point of views. The East German short Leuchtkraft der Ziege (The Goat’s Intensity, 1988) and Helke Misselwitz’s Herzsprung (1992) have rural settings, which is rare. Most are set in an urban milieu. Berlin in the 1980s is dominant since it has been turned into pop culture iconography, which makes it especially interesting for younger audiences. Chapeau Claque and Macumba (1981) are both set in Berlin, but their primary locations, a run-down villa and a condemned building, given the limited financing, generate an idiosyncratic cinematic dimension that goes beyond the city of Berlin. Meanwhile, Die Deutschen und ihre Männer (The Germans and Their Men, 1989) goes to the West German hinterlands, namely Bonn, where the protagonist searches for a forever-man –, at the dying political centre of the old West Germany of all places. Christoph Schlingensief’s Das deutsche Kettensägenmassaker (The German Chainsaw Massacre, 1990) takes a completely different tack, but explores similar West German sensibilities about reunification.

Florian Lukas and Christian Kuchenbuch in Banale Tage (Banal Days) by Peter Welz

Film production in East Germany was subject to state control. But you still managed to find examples of East German “alternate cinema”. What is the relevance in them?

RR: Like every sizable film company, DEFA aspired to exclude the unconventional. Everything that seemed beyond its control was a challenge for DEFA. But there are films that deviate from that. Denk bloß nicht, ich heule (Just Don’t Think I’ll Cry), say, could only have been made in the specific context of the years 1965/66. The feeling of the time was that films critical of society could be made – which led to the ban of Frank Vogel’s film. After the collapse of East Germany, DEFA changed its business model. When it became clear that its role as a large-scale central film production company was coming to an end, the studio management started to support projects that DEFA would have never touched before. That includes Banale Tage (Banal Days, 1991) by Peter Welz and Herzsprung by Helke Misselwitz. The irony is that those films would have sparked enormous interest in East Germany, but were no longer relevant for audiences that faced other problems in the years after 1990. The 1990s were the decade of comedies. Back then, it was: no experiments, please! This applied not only to DEFA films, but also to West German productions.

Ismet Elçi in Kismet, Kismet

AH: It will be interesting to see how a modern audience views those films. I think it is time to re-discover them, especially two films from Berlin’s alternative scene – the immigrant drama Kismet, Kismet (1987) by Ismet Elçi and Jesus – Der Film (Jesus – The Film, 1988), a cooperative Gesamtkunstwerk led by Michael Brynntrup. On the other hand, the line-up includes Nicht nichts ohne Dich (Ain’t Nothing Without You, 1985) and, yes, that’s a recommendation. Pia Frankenberg’s film is unbelievably light, charming, and amusing, and is one of my personal favourites. It’s a film with its tongue firmly in its cheek, like her Berlin film Nie wieder schlafen (Never Sleep Again, 1992), which was the re-discovery of the 2019 Retrospective.

One doesn’t expect premieres in a Retrospective. Will there be films that will be seen in their digitised version for the first time at the Berlinale?

RR: At least two. Ich (Me, 1988), a very witty dffb production by photographer Bettina Flitner, and Unsichtbare Tage (Invisible Days, 1991) by Eva Hiller. Thomas Mauch was the cinematographer of her essay film and his images of night-time Frankfurt are a unique, visually enthralling experience.

Unsichtbare Tage oder Die Legende von den weißen Krokodilen (Invisible Days, or the Legend of the White Crocodiles) by Eva Hiller

AH: The restored Fegefeuer really also belongs in that category; it has only been shown twice. And we are presenting the latest digitisation of Will Tremper’s Die endlose Nacht , which was done specifically for the Berlinale. The 23 films in the Retrospective, and its many guests, will be complemented by a Kinemathek streaming programme, which has been showing additional films in the category “alternative cinema” since February 1, including films by Lothar Lambert, Helma Sanders-Brahms, and Andreas Kleinert. There is a very extensive variety of choice available. And yet, it is nonetheless small when you think about the fact that the Kinemathek holds some 22,000 films. About 17,000 of those come from DEFA, but the 4,300 from the SDK collection are also worth noting. It was only thanks to tips and suggestions from the colleagues in the film archive that we were able to narrow down the selection.