2024 | Encounters

Underneath our Reality

Ghosts, Sappho, treasure hunts - in its fifth edition the Encounters section seeks to explore and question the limits of genre and cinematic truths. Artistic Director Carlo Chatrian and Head of Programming Mark Peranson discuss the 15 selected films and cinema’s quest to make the invisible visible.

Tú me abrasas by Matías Piñeiro

The Encounters section aims to explore the limits of the attempt to categorize and restrict film. One of the most discussed aspects of this categorization is the division into fiction and documentary. Do you have examples of this “border crossing“ in this year’s selection?

Carlo Chatrian: Film as a business is based on categories because that's the easiest way to put films into a box and fund them. When it comes to the art of making films, in most cases distinctions are blurred. The filmmakers that we have selected for Encounters throughout the years have even less concern about these categories. A film that starts as a documentary can become something different because that's where the process leads them to. A film like Tú me abrasas (You Burn Me) by Matías Piñeiro is impossible to define. Is it a documentary on Pavese and Sappho? Is it a love story? Is it an essay film? Is it a film about painting and music? I think this is precisely what we want to bring into the picture with Encounters. Cinema is based on moving images; it‘s always more than what you can express through words. In the end you always watch a film that is bigger than the label or box you want to put it in.

Mark Peranson: In Tú me abrasas you're dealing with texts of which only fragments remain. There is only one poem surviving by Sappho. The way to accurately portray such a circumstance is to fill in the gaps with cinematic means, but also realise that ultimately you can't fill everything in. By putting these unfinished poems into a dramatic structure - with songs, with images, with words, with a relationship - it somehow brings them to life. But always with the acknowledgment that the sense of being incomplete will always exist.

Police detective Ivan Peric in Through the Graves the Wind is Blowing by Travis Wilkerson

MP: Generally when you watch a film in Encounters, you realise that it is made by a human being. Even when they are making a big budget movie, it's still a very personal film. You can see and tell that there's somebody behind the images. Of course, the budget of the film also influences the amount of freedom you have as a filmmaker. The more money you have, the less freedom you have. With Through the Graves the Wind is Blowing by Travis Wilkerson – a film set in Split, Croatia that is about a police detective and also about fascism and the long-term effects of the breakup of Yugoslavia – we don't know what the budget of that film was and I don't think the filmmaker knows it either. He woke up every day and decided to shoot something. The result is totally hybrid. I asked him if it‘s a documentary or a fictional film and he said he didn’t know and also didn‘t really care.

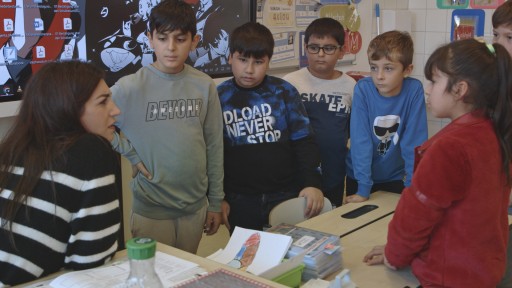

Staying with the films that tend to be more on the documentary side - in Ruth Beckermann's Favoriten, we spend a lot of time at a Viennese elementary/junior high school. In addition to many funny and touching moments, a long sequence in the middle of the film shows the teacher asking the children about their information and opinions on the war in Ukraine. She receives interesting and challenging answers. What do you think of this specific insight into a cross-section of our society?

Ruth Beckermann's Favoriten

CC: At first Favoriten may look like any other film about a school class. And it's always fascinating that by filming a class, you film society. Actually, you film the way society looks and the way society is shaped. And clearly the choice of a class where most of the students are sons or daughters of immigrants is very deliberate. Ruth Beckermann pays a lot of attention to what she puts on screen by adding elements here and there, like the discussion about war, to point out that it's a documentary about a class, but there are different layers at play. She is conscious of cinema as a tool and the fact that when we talk about something or learn something, it is always the result of a projection. Usually when you watch a film about a class, the teacher addresses the students and the students react emotionally. In Favoriten, it's the opposite way around, which ultimately is the most impressive achievement of the film. At the end, the most moved person is the teacher and not the kids. On a very simple level, it's good to show that even adults can be moved because we tend to associate strong emotion, like tears, with children.

Film and truth

The close and often complicated relationship between the search for truth and the act of filming is also negotiated in Mãos no fogo (Hands in the Fire) by Margarida Gil: a young documentary filmmaker tries to capture the everyday life of a camera-shy family living in an old Portuguese manor, only to discover that the family is making their own films - and even have the protagonist herself in their (camera) sights. How does this film deal with the tension between film and truth?

Carolina Campanela as a young filmmaker in Mãos no fogo

Mãos no fogo is a film on a film. It‘s a film that is shot in a place where other films were shot. The previously shot films belong to a different era and in the act of filming a secret is being told. And here we are again talking about the relation between genres. I found quite striking that Margarida Gil tackled the power of the camera to trap people from a female perspective.

Something we are quite conscious of in Encounters is that most of the films show that there is no truth. Or they at least give the audience a specific position, which is not “I take you by the hand and I show you things”, but rather “If I take you by the hand, I show you that I'm taking you by the hand”. Hands on Fire is a film that very clearly depicts this.

Direct Action

MP: To divert to another movie, Direct Action by Guillaume Cailleau and Ben Russell. The film documents the everyday lives of one of the most high-profile militant eco activist communities in France and one could say that the filmmakers are trying to capture truth with long shots. But in the climactic protest scene somebody comes up to them and says that they're pointing the camera in the wrong direction and therefore not showing the right thing. So everything, every choice that a filmmaker makes, is always a filmmaker's truth as opposed to objective truth.

Another film that leaves a lot open for the audience to discover is Khamyazeye bozorg (The Great Yawn) by Aliyar Rasti, an Iranian film about a treasure hunt and the potential conflict of religious belief and dreamy imagination.

Khamyazeye bozorg by Aliyar Rasti

MP: The film also doesn't want to guide the audience in a certain direction. The treasure, in classic cinematic terms you could call it a MacGuffin, propels the plot. You're invited to project yourself into what this search is about and maybe discover that in the end it doesn’t really matter what they find but the search itself is the point. They might not even find anything and just keep looking, keep looking, keep looking. Which is, in a way, also kind of a metaphor for cinema. Film is essentially the art of trying to make the invisible visible. Just like there's no objective truth, there's also really no objective realism. I mean, on a philosophical level, cinema used to be a photochemical process. Now it's a digital process of somebody filming somebody. So at the heart of that, there's always an illusory aspect to it.

CC: We were very surprised with Khamyazeye bozorg because it's not the usual film you expect from Iran. After the beginning, which depicts a “casting” where the protagonist is looking for the right person for its quest, it doesn’t really focus on society anymore or not in a realistic way. The journey quickly becomes something more metaphysical and existential. But it also features elements of humor here and there. We know that we will never solve the unsolvable. Aliyar Rasti plays with the idea of not giving the goal - like many films in Encounters: it's not about finding the result, it's more about what happens along the line.

On ghosts and treasures

Papoulia Angeliki in Arcadia by Yorgos Zois

Arcadia by Yorgos Zois tells a ghost story and asks what it means to remain connected to a deceased person. A very literal reflection on the statement "I still carry them with me". Were these questions at the forefront of your selection or were the innovative and sometimes very bizarre rules of the spirit world the deciding factor?

CC: Arcadia is a ghost story, a love story, a story about cheating, a story about a bar frequented by dead people. It's a story about how reality fades away every time, and this is something that connects the films. What I personally like is that it is very hard to capture the film in one single element. Because you might label it as a ghost story or a zombie story but if you explain the film to a friend, I'm sure they will have a different take, because it doesn’t feature the usual types of ghosts or zombies. The film fights against realism, which is very relevant because nowadays we are surrounded by images and think that images are reality.

To fight against realism

Demba by Mamadou Dia

CC: All films in Encounters fight against this perception. So at the end it's not realism that makes you feel connected to a film but the narrative, the style, the frame, the sound – all of it together – that create the sense of connection. Demba by Mamadou Dia is another perfect example of that. It tells the story of an aging man in crisis who is grieving his wife and is asked to retire. But it's much more than that. It's also a story about a father and a son reconnecting and a story about bureaucracy in Senegal.

Monogamous relationships are broken up by external participants and internal conflicts. Cheating seems to be a topic in a few films like Eva Trobisch's Ivo, Kazik Radwanski's Matt and Mara and Arcadia. Why is film a suitable negotiation space for questions about established relationship norms and dynamics?

Matt Johnson and Deragh Campbell are Matt and Mara

CC: Relations are always ambiguous. It might involve cheating but it’s more about a problem in communication: I give you a message and you receive a different one. I think most of these films deal with this circumstance and the fact that if you have the desire to communicate, you also have to do so on a very primal level by making love or just being together. In this communication there is always a distance, which I find interesting. This year, maybe more so than the years before, we have films that deal with sensual love. Maybe cheating is the most visible version of this form of (mis)communication, because it’s so conventional, it's the most banal thing that you can do in a relationship.

MP: Technically, there's no cheating in Matt and Mara. It's emotional cheating which is a bit different. Somebody comes in from the past and it stirs up old emotions, and that's something that everyone experienced at some point or another. It's a film that touches on infidelity, but there's universality to the way the subject matter is treated.

I would say what links a lot of these films is that – maybe you can sense it – they are very specifically rooted in a place or in a way or behavior which is typical to specific countries or cities. Matt and Mara, for example, is not a film about for example New York. It's very much a film about Toronto. We can apply this to any of the Encounters films and where they are taking place. The Brazilian film Cidade; Campo by Juliana Rojas is partly about the city but then the film moves to the countryside – how do the characters behave differently in these locations? If you take location as a framing device for these films, then maybe you can look at ideas of, say, infidelity or cheating and observe how they play out differently in these places. What does that say about the place where the film takes place?

The Fable by Raam Reddy

A matter of location

CC: Yeah, this is very true. I think there is the tendency to think that Encounters films are only primarily an exercise in style. But actually every year, and this year even more, the places these stories are rooted in are really essential in every film. For example, The Fable by Raam Reddy. The filmmaker spent months in this area, in the mountains of India. Or Favoriten, which is literally the name of the area in Vienna the school is located in. In a film like ) by Christine Angot, the most striking scene is when the filmmaker and the protagonist step into a house which is the real house in which bad things happened in the life of the filmmaker.

Another potential connecting element of the films might be the question how one can deal with the death of a loved one and the associated grief and responsibility. How do the films deal with pain? Why does this topic reappear in this year's selection?

CC: While many films in the Competition selection are really about confinement and a tendency of trying to break out of it, the Encounters selection is, to me, more about tenderness. It's more about soothing the pain or learning how to live through the pain. And I think, again, that cinema is able to capture something that is underneath our reality. We are all concerned about the world we are living in and maybe we are even more concerned now than we were five years ago (before the pandemic, just to put that as a mark). And therefore, the films reflect that. Maybe not in a direct way, but with their stories. So these are not neccessarily coincidences, but points where different trajectories overlap. Confinement, in Encounters, can be pressure that comes from outside. But the films are more concerned with how do we deal with suffering or loss that we are experiencing as a community or as individuals, either in a direct or in a metaphorical way. This includes the loss of freedom, the loss of saying what you would like to say.

Une Famille by and with Christine Angot (left)

How is the make up of the filmmakers behind the Encounters selection this year?

CC: This year we have less first features, there are more sophomore films. We have a good number of second feature-length films: Dormir de olhos abertos (Sleep with Your Eyes Open) by Nele Wohlatz, The Fable, Arcadia, Ivo. But this is not necessarily what we think about when we do the selection. Encounters is also not exclusively a section for first and second feature-length films. It's a section that embraces different kinds of filmmaking. We are interested in having a good balance between new voices and established filmmakers. Kong fang jian li de nv ren (Some Rain Must Fall) is a first feature, but the short films of the director Qiu Yang were awarded, including the Palme d’Or for Best Short, so his is a highly expected debut film. The Great Yawn was probably the biggest surprise. Christine Angot is a well-known writer and a public figure in France who also wrote Claire Denis’ Berlinale awarded Avec amour et acharnement (Both Sides of the Blade). I don’t consider Une Famille a debut because it comes from a person who has already shaped culture.

Kong fang jian li de nv ren (Some Rain Must Fall)

MP: A lot of these films we were tracking for a long time and waiting for them to be completed. There are many other films that we liked but couldn't show. Here it’s the same situation. Some of those are first films, some are from veterans who had films in Encounters before. But with a selection of 15 films, you want to create a balance of certain things in the selection. And the coincidences that you see are not something that we're thinking about when we're choosing the films. It's something that we discover afterwards, almost always surprisingly.